Volunteer firefighter Kelly Browne climbed down a steep embankment in the thick bush of Sydney's Sutherland Shire.

The captain of the Waterfall fire brigade - and a volunteer since she was 13 - was trying to build a picture of the emergency situation described to her: a four-car train derailment, multiple injuries, and the possibility of death.

As she reached the crash site, an almost cinematic scene unfolded.

"It looked like a movie set," says Browne. "It just didn’t look real. It was so surreal to to see a four-car Tangara with the first two carriages fairly smashed up, the roof ripped off the first carriage and the last two carriages on their side and you know people kind of walking around all … grey and with dust all over them."

"I remember thinking how eerily quiet it was for for such a horrific scene." As she took in the scene from the hill, she experienced something not uncommon among people first on the scene of an emergency: surprise.

As she took in the scene from the hill, she experienced something not uncommon among people first on the scene of an emergency: surprise.

Eight people were killed and 23 injured in the crash near Waterfall, NSW. Source: Getty Images

"I stopped and I stared," she says. "It would have only been seconds ... but just time to process what I was actually looking at, before I kind of kicked straight in to operational mode and and the training kicked in."

It's a response psychologist Dr Rachael Sharman, from the University of the Sunshine Coast, is familiar with.

"A lot of people in these situations will simply stop and they will try to process the scene, try to understand what’s going on there," she says.

"Even your facial expressions have a function here. Your eyes open wider, so you can actually have more peripheral vision, so you can see what’s going on. And your mouth opens, because you’re preparing to scream or to actually inhale and run. So the emotion of surprise is just there to have people stop and process."

The emotion of surprise is just there to have people stop and process

Peter Davidson, a rescue paramedic, remembers being "just blown away with what we were seeing" as he arrived in the first helicopter responding to sinking yachts in the infamous 1998 Sydney to Hobart.

Looking out at the conditions - 80 foot waves, 160 km winds, injured sailors stranded in a flimsy lifeboat or on their sinking boat - his initial reaction was that the whole mission was impossible.

But after the shock of that first glimpse at the scene out of the helicopter window, a plan began to formulate. After numerous attempts, Peter finally dragged himself through the sea to reach the boat and begin the two hour process of rescuing eight sailors.

Davidson says the experience was very adrenaline-driven; an important hormonal reaction to an emergency, says Sharman.

"Adrenaline tends to give people a very singular focus ... that adrenaline pumping through tends to get people extremely goal directed." she says.

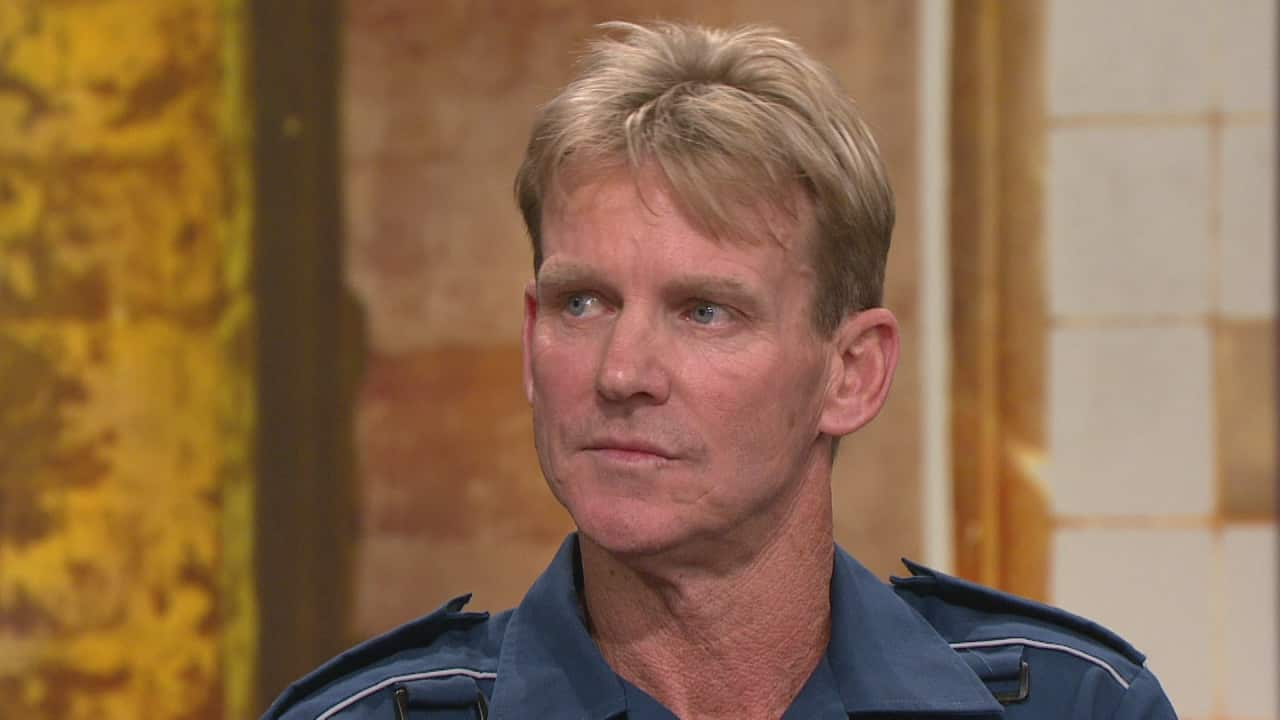

Rescue paramedic Peter Davidson on this week's Insight. Source: Insight

Surprised or frozen?

While surprise can help kick-start thought processes for coping with an emergency, the 'freeze response' actually shuts things down.

"The freeze response stops you from processing information," says Sharman. "It seems to be a protective response, so we don’t become so overwhelmed that the situation basically drives us insane, that we’re so overwhelmed, we can’t escape, we can’t fight.

"We’ve just got to do what we’ve got to do and just disassociate from the situation."

Another theory around the response is that it comes from a primal instinct, "a very basic reptilian hind-brain kind of response where you freeze to play dead," says Sharman.

She says these theories can explain why some people don't remember details of an emergency, as the freeze response stops the collection and laying down of memory, almost for psychological preservation.

Such was the experience of Alastair Boast, a former Monash University student who joins this week's Insight on being the first on the scene of an emergency.

As a student in 2002, he was in a small tutorial when a fellow student opened fire on the classroom.

"I remember hearing one sort of loud, loud noise, and instinctively I just hit the deck, hit the ground and curled [up] almost like a little foetus into a small little ball, as other loud noises in the room occurred," he tells Insight's Jenny Brockie.

During a break in the shooting, he stood up and charged towards the shooter, tackling him to the ground and restraining him with the help of his lecturer.

Years later, Boast has very little memory of how this all happened: how he got across the room, his thought process at the time, even if the gunman spoke to him.

"I have very little recollection of what happened in those moments," he says.

Alastair Boast on this week's Insight. Source: Insight

Peter Davidson, Alastair Boast and Rachael Sharman on Insight's show, First on the Scene, looking at what it's like to be the first on the scene of an emergency | Catch up online now:

[videocard video="696180291883"]

More on reactions in an emergency

Could you help in an emergency?