In retrospect, it was a case I should never have agreed to take. The year 2014 had been a difficult one for me on a personal level. My ex-wife and I had divorced, and were doing our best to muddle through setting up new lives as single parents to our two kids. There was a lot of goodwill and co-operation, but it had nevertheless been a draining, emotional year.

The difficulties with me taking on this case were plain to see. The accused was recently divorced. He murdered his two children – aged roughly the same as mine – and surrendered himself to police. The emotional content of the case was obvious and raw, and I was already at a low ebb. If I'd said no to representing him, I doubt that anyone would have thought me less professional for the decision.

By that stage I had been practising criminal law for more than 15 years. As a barrister, I had never turned down a brief. Ethically, I had been bound to take any brief I was available for – a principle known as the cab-rank rule. I was working in-house for Victoria Legal Aid, and although the rule no longer strictly applied to me, old habits die hard and I felt it was important that I take the case. Besides, if I refused it, one of my colleagues would pick it up and many of them had young families like me.

So I buried myself in the case, researching similar child homicides in Victoria and interstate to get a handle on the likely issues and sentencing range. I had lengthy conferences with the client and read psychiatric reports. I marshalled my arguments and prepared for court. I got on with the job.

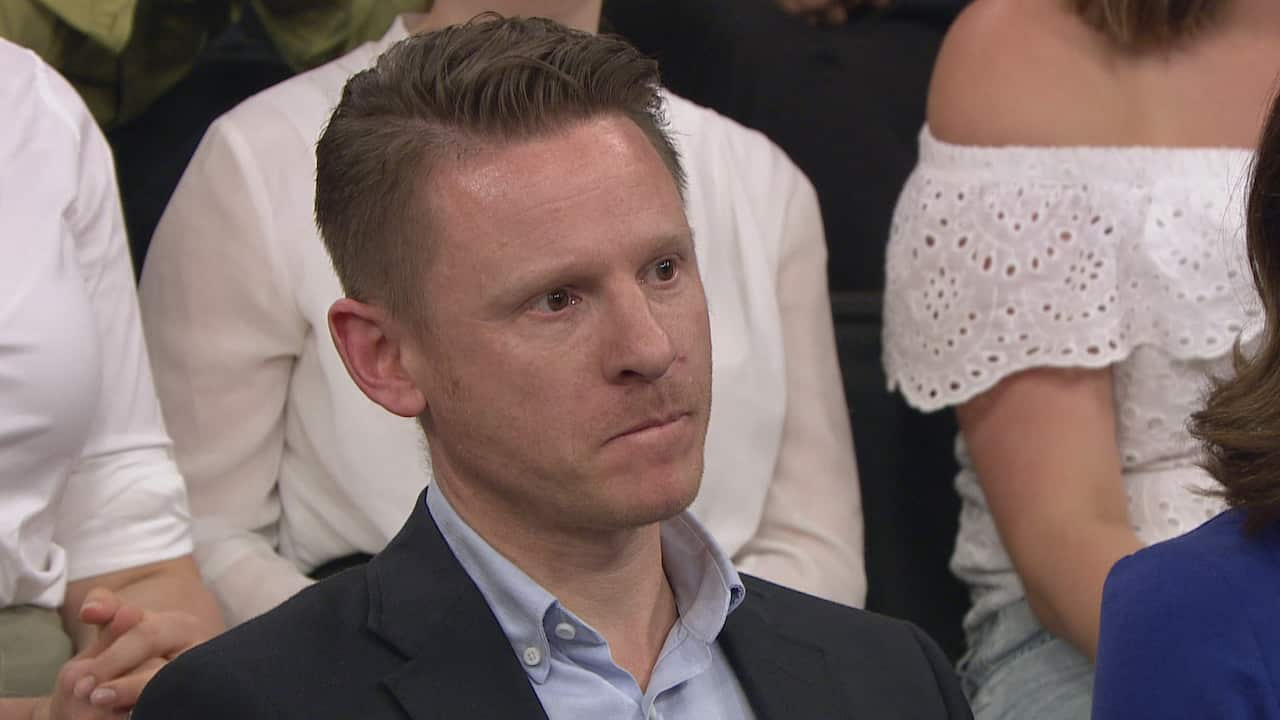

Source: Insight

The real impact didn't hit me until after he was sentenced. I couldn't get the details of the case out of my head. Phrases and images ran on a loop day and night. I was distant from my kids and snappy with my colleagues and friends. I stopped eating and slept poorly. I felt irrationally angry all the time.

I would like to think of myself as someone who is pretty clued-in about mental health. Almost all of my work involves seriously mentally ill clients, and I had worked on the Mental Health Review Board for a number of years. However, knowledge is not insight, and I was well on the way to an emotional crisis before it occurred to me that I was suffering from depression and needed to seek help.

Fortunately, I work for an organisation with a comprehensive employee assistance program – on-call counsellors and psychologists available to all staff. And even more helpfully, the psychologist I got an appointment with was a good match for me. There were a few more ups and downs, but the fog eventually lifted.

My experience helped inform the development of a more comprehensive mental well-being program at Victoria Legal Aid, focusing on building resilience, peer support and crisis avoidance rather than relying on crisis management after the fact.

My experience is far from unique. I've watched friends and colleagues as they have grappled with workload, anxiety, emotional trauma and mental exhaustion. Repeated studies have shown the legal profession to be home to some of the highest rates of anxiety and depression in the workforce.

That this kind of violence lurked inside us, and inside men in particular.

One study in particular identified that lawyers working with traumatised clients – criminal defence lawyers and prosecutors – suffered more vicarious trauma effects, depression, stress and adverse beliefs about the safety of themselves and others than lawyers who didn't work with traumatised clients.

Clearly, the impacts of vicarious trauma aren't confined to either the defence or prosecution sides of the adversarial process. Prosecutors often work closely with highly traumatised victims – people whose trauma may become re-enlivened by the court process itself. Defence lawyers work in a similarly emotionally charged environment, providing advice and support to an accused and their family – people experiencing one of the most stressful events you could imagine going through, a criminal trial.

And both sides of the case are exposed to the facts of the case. Photographs of deceased victims. Harrowing triple zero emergency calls. Graphic descriptions of assaults and injuries. All of these things posing the almost unanswerable question: Why do people do these things to each other?

It was this question that nearly undid me at the end of 2014.

As long as I had the intellectual scaffolding of preparing for the plea hearing in the Supreme Court, I could keep any personal feelings at bay. But the moment the case was concluded, I was confronted with the full horror of what had occurred. That someone could kill their own children to spite or wound an ex-partner. That this kind of violence lurked inside us, and inside men in particular.

Despite what I've written, I remain fundamentally attracted to this work. Many of my friends and colleagues, whether they prosecute or defend, say the same thing: the work matters. In any week, the advice I give and the decisions I make have a profound impact on individuals and on our society in general, and I wouldn't want to give up that relevance.

The challenge for many of us is to try and find the stable distance that allows us to experience the empathy and connection which informs good advocacy, but keeps us from getting drawn in and consumed by the darkness of the subject matter and the ongoing trauma of our clients' lives. It has never been an easy balance to find.

Share

Insight is Australia's leading forum for debate and powerful first-person stories offering a unique perspective on the way we live. Read more about Insight