Pictures by Damien Pleming

Fleeing Iran for Australia as a child, Rita Panahi knew only two words of English. Her family was penniless. Today, she's an opinion columnist and controversial critic of Islam, a single mum with a real estate portfolio. But are her views as mainstream as she thinks?

Suddenly, it seemed, Rita Panahi was everywhere: on TV panel shows, talkback radio and in News Corp newspapers, full of right-wing opinions – like Andrew Bolt, yet very unlike him.

Her Twitter account, which she uses to tangle with her critics and attack "leftie lemmings", has this quote from British wartime prime minister Winston Churchill in the space where most people say something about themselves: "The truth is incontrovertible. Malice may attack it, ignorance may deride it, but in the end, there it is."

It captures two things about Panahi. She sees herself as a woman of integrity and of truth. And, like so many commentators from both the left and the right in these opinionated times, there is a strong sense of incipient persecution – of a courageous truth-teller under attack.

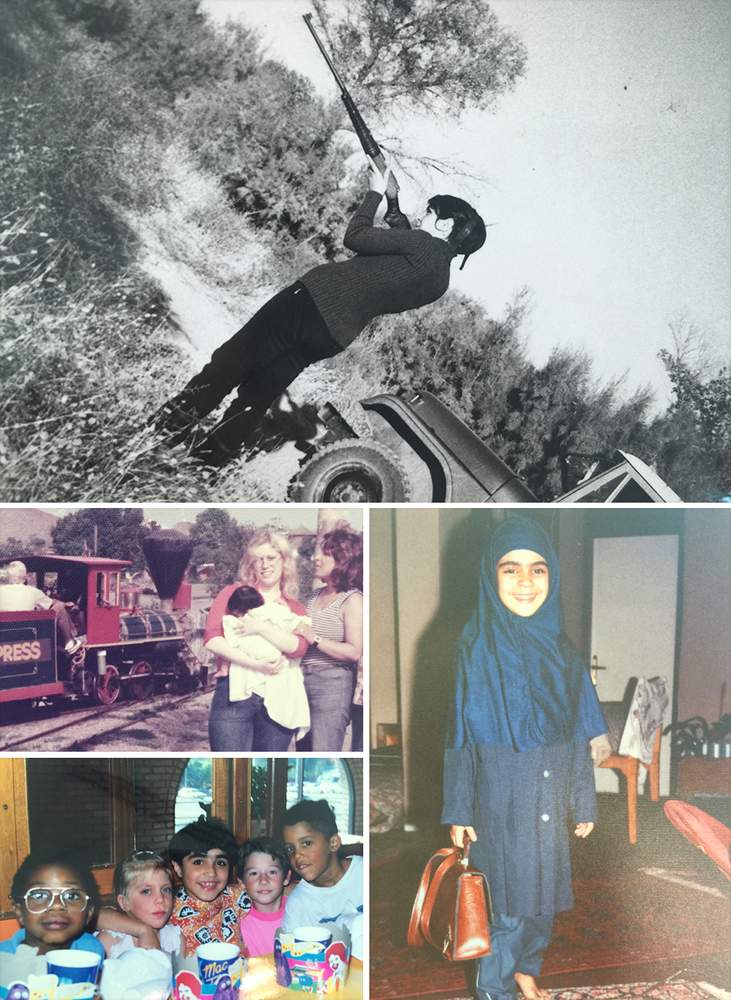

Tweeting pictures from her Tehran childhood, when she wore a hijab and chanted anti-American slogans at school, hints at major change. How did that little girl grow up to be Rita Panahi, Australian public figure?

It is surprising that she is being interviewed at all for this profile, given that she claims her colleagues have warned her the result will be biased, nasty, distorted and an example of exactly the kind of left-wing stupidity she so often attacks.

To Panahi, radical Islam and Western values cannot peacefully co-exist and Australia is the least racist of nations.

Nevertheless she has agreed to co-operate and be interviewed, once in print and once for video. She first meets me in the cafe on the ground floor of the Herald Sun building. In person, Panahi belies her belligerent style. She is likeable – physically small, obviously fit and full of barely-suppressed energy. We talk for over an hour and she is frank, considerate, apparently trusting, sometimes vulnerable. She is clearly tough, but at one point she cries. She says she doesn't trust me – and yet she is trusting.

Towards the end of the interview, she asks why I think it is that most journalists are left-wing. It doesn't seem to be a rhetorical question.

Even at the Herald Sun, she says, a paper which reflects middle Melbourne, which she "adores" and has worked very hard indeed at breaking into, most of her colleagues are to the left of her – and she sees herself as mainstream. Why should this be?

Perhaps, I suggest, those in occupations that deal with ideas and are dominated by the white middle class are more likely to consider radical change. Whereas those like her, who bear the patina of hard knocks, are more inclined to conservatism, valuing the security of what is already there.

She listens with a care that might surprise her readers. As the most recent recruit to the stable of News Corp right-wing columnists, Panahi is not normally open-minded about those on the left. Read her work and you come away with the impression that she regards those with whom she disagrees as mad, sad, stupid or bad – sometimes all four.

Is Australia a racist country? Are Muslims treated badly in Australia? Rita Panahi talks about her views.

Anyone with an IQ above room temperature, to coin a favourite Panahism, would surely see that Islam has a problem, that women should be banned from wearing the burqa, that radical Islam and Western values cannot peacefully co-exist and that Australia is the most accepting and least racist of nations.

To Panahi, anyone who is not a "wing-nut" would know that a good deal of university education is of dubious value and that while gender equality is an admirable aim, feminists are hypocritical nut jobs who don't care for truly marginalised women but instead make a fuss about trivia and harmless jokes.

Those who protested against the East West link, in Melbourne's suburbs during the last Victorian election, she sees as a "ratbag gang of unionists, unwashed hippies, NIMBY greenies, bellicose socialists, confused pensioners and progress-hating layabouts".

Giving money to beggars is "akin to voting for the Greens – it only encourages them, and prevents them from doing something useful with their lives".

And in Panahi's view, Tony Abbott lost popular support partly because of his inability to communicate, but mostly because of a vehement media campaign by left wing journalists.

Was his downfall evidence that the majority of Australians are less right-wing than she might think? Not at all: "I think the centre is a lot more to the right than most people in the media would like it to be," she says.

It's the left-wing commentators, the feminists who write for Fairfax's Daily Life – and the "nut jobs" who deride her on social media – who are the controversial ones, on the fringe. As for herself: "I am, for the most part, reflecting mainstream Australian values."

"I'm not your plastic conservative. I'm ethnic, a migrant, an atheist. I'm a single mum."

The Herald Sun's national political editor, Ellen Whinnett, counts Panahi as a friend.

"I don't always agree with her opinions, but we have great discussions and arguments about politics,” says Whinnett. “She's a really interesting person and I admire the way she deals with the abuse she receives on social media, and the fact that she remains relentlessly positive and upbeat. Plus we share a deep love of the mighty Hawthorn Football Club."

Another colleague says, "She is a great, ballsy, brave woman. She'll take anything on. It's very hard not to be fond of Rita."

Not everyone would agree. Her strong views and take-no-prisoners style has begun to attract the same kind of heat – and vehement social media abuse – that is usually visited on her older colleague, Andrew Bolt.

But whereas Bolt had a standard journalistic training before he became an opinion writer, Panahi seems to have come from nowhere, springing fully formed on to the national stage as the main female right-wing voice on Australia's largest circulation daily newspaper.

She is increasingly part of debates that matter. She was, for example, on the opposing team to Stan Grant in a debate on racism that went viral in early 2016 over Grant’s speech. Panahi spoke immediately after Grant and said she was moved by his address. But she still asserted that it was wrong to characterise Australia as racist.

She protests that she is not particularly interesting and not worth the attention of a profile. One of her colleagues and long-time friends doubts the modesty is genuine: "She would love it. It would thrill her. And that would outweigh the caution."

Panahi is well remembered at the Herald Sun for the way she courted the senior people on the paper when she was still an occasional contributor. One Christmas season, she went around distributing gifts of expensive alcohol and chocolate.

She represents, some suggest, the next generation of conservative opinion writers – Bolt's heir and successor. Yet she is very different from Bolt.

"I'm not your plastic conservative,” Panahi says. “I'm someone who's ethnic, a migrant to this country, an atheist. I'm a single mum, I'm not some privileged, middle-aged white man who would normally have character traits ascribed to conservatives.

"But I do have an issue with people who haven't got my life experience patronising me with their opinions. You know, privileged, middle-aged, middle income white people, who were born and bred here, telling me my views on racism and a cohesive Australian society are wrong."

"My uncle was arrested, my cousin had been shot... There were raids and they thought that would come for us."

In January this year, she clashed on live television with Sunrise host Andrew O'Keefe, in an exchange about Islam and terrorism that went viral.

“We need to start discussing intelligently the issues we have with the Muslim community,” Panahi said. O'Keefe bit back: “Every time a fundamentalist Christian in the United States bombs an abortion clinic or bombs a synagogue, do we hold all the Christians in the world accountable for that?”

Panahi responded: “Andrew, that’s such a nonsensical argument... We’ve got to stop doing what you just did and pretending like Islam is like any other religion, as far as being behind incidences of terror.”

For these views, she claims a particular authority. Panahi comes from the heart of the modern conflict between western traditions and radical Islam. She and her family were refugees from the Iranian revolution of 1979, in which the western allied Shah of Iran was overthrown by the repressive theocracy of the Ayatollah Khomeini.

That was the first time the western world was shaken by the power of radical Islamic resurgence and its hatred of the west. This was the revolution that redrew the map of global alliances. We are still roiling in the aftermath, and Rita Panahi as an influential critic of Islam is one of the legacies.

"Hello" and "tea" were her only English words. Rita Panahi recalls her family's arrival in Australia.

Rita Panahi was born in 1976 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, while her Iranian father was studying at the local university to become an agricultural engineer. Her mother was a midwife. When Rita was still an infant, the family returned to Iran. Her first memories were of an idyllic life on the Iranian coast.

By 1979, the family had moved to Tehran. Panahi was still little more than a toddler, but she remembers the mounting fear when the Shah was overthrown and the Ayatollah came to power. Panahi's mother had worked in a senior midwifery position at a hospital that bore the name of the Royal Family and was patronised by them. This put the family on the line. Photos of Panahi’s mother with relatives of the Shah had to be burned or hidden.

"People were being imprisoned,” Panahi says. “People were being killed. And people fairly close to us; they were in our family."

"English is a very easy language to learn... I think I learnt it mainly on television."

Her parents, she says, were not particularly political. They are what she describes as "relaxed" Muslims. Nevertheless, the family was targeted.

"My uncle was arrested and considered an enemy of the state and my cousin had been shot. That was enough for you to be under suspicion... I remember not being able to go home certain nights because there were raids being done and they thought that would come for us."

Meanwhile she was made to feel the weight of being female. One of her keenest childhood memories is of having had a head injury, which caused her hair to be shaved. Suddenly, people thought she was a boy. This meant freedom.

"I absolutely loved it. For as long as I could, I kept asking my parents to shave my hair and they humoured me for a few months. I think it was just the sense of freedom where you didn't have to have the hijab and you could play with the boys."

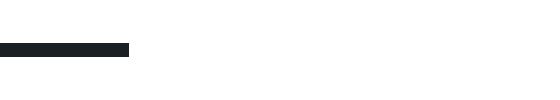

Clockwise from top: Rita's mother Zinat holds a gun in pre-revolution Iran; Rita as an Iranian schoolgirl; a birthday in Australia for Rita's brother Reza (centre); baby Rita in the US with her aunt and mother.

These memories have given her a strong contempt for those who, as she puts it, "appease" strict Islam. In October this year, she wrote about her childhood as part of a column decrying the fact that Muslim children attending a Melbourne school had been excused from singing the national anthem because they were observing Muharram – a month of mourning for Muhammad's grandson.

"When I was a little girl in Tehran," she wrote, "we would line up in neat rows, dressed in our dehumanising Muslim garb, and chant “death to America” over and over again before commencing our classes.

“It was a little tricky for me, given I was American-born, and even at the age of six loathed the hijab and all it represented, but it was what the school required and I stood there and silently mouthed the words."

How foolish and wrong, she argued, that Muslim children should now reject a joyful act such as singing the national anthem of their adopted country.

"Wogs, in my experience, are also more likely to live by the philosophy that you bite off more than you can chew and then chew like hell. None of this 'your mortgage payments shouldn't exceed 30 per cent of your net income' nonsense."

Watever the method, in her early 30s, on her own and with a baby, she was able to effectively retire and concentrate on motherhood and her pitch for a journalistic career. Meanwhile, feeling her lack of tertiary qualifications was unfinished business, she enrolled in and completed a Master of Business Administration from Swinburne University. She is glad to have the qualification, but it hasn't altered her scepticism about university degrees.

Her first column for the Herald Sun appeared in September 2007, when her son was a newborn. It was, she says, a "mummy blogger type piece" – a fierce advocacy for breastfeeding. The tagline at the foot of the article, and the ones that followed, described her as a "social commentator", which at this stage of her career was, to put it mildly, a stretch.

The Panahi belligerent style was already evident:

"The endless rationalising by feminists of why women do not breastfeed is more to do with a political agenda than providing real answers. The unpalatable truth they do not want to acknowledge is that despite society being supportive of breastfeeding, many smart, educated women simply choose convenience over giving their child the optimal start in life. It's not chauvinistic male attitudes, but female prerogative that is behind Australia's poor breastfeeding record."

This, she says, is one of the few issues on which she has softened her attitude. As a new mother, she was obsessive about doing everything right by her child.

"I was so pedantic with diet,” Panahi says. “When he was off breastfeeding, everything was homemade. Pure and organic. Now I'm a lot more relaxed, feed him all sorts of junk. Back then, I was a lot more conscientious."

By 2008, she was a regular contributor, but still not on staff – and "paid a pittance" for her freelance pieces. She wrote on everything from fast food (parents should just say no) to slow walkers who clog up the aisles in the shops. These were, she said, to be added to her "ever-expanding list of pests, irritants and inconsiderate muppets" together with "smokers, hoons and men who spit in public".

She commented on films and football, and, controversially, on the disappearance of Madeleine McCann. The parents, she wrote:

"… should be charged with neglect for leaving a four-year-old girl and twin two-year-olds alone and unprotected in a hotel room for up to 30 minutes at a time. Any decent parent can tell you a lot can go terribly wrong in that time, even without an intruder."

Sympathy for them was misplaced and a symptom of "bleeding heart syndrome", she wrote.

Slow walkers joined "smokers, hoons and men who spit in public" on her list of "pests, irritants and inconsiderate muppets".

By now, the paper was describing Panahi as a "Melbourne writer". She was gradually broadening her range into politics and social affairs. When the right-wing talkback radio station MTR launched in 2010, Panahi was a regular.

She wrote against a 40km/h speed limit in the Melbourne CBD ("a harebrained scheme") and that she thought racism in the AFL was overstated, but that action was needed to combat homophobia.

"Elite professional sportsmen from a host of other sports have revealed they are gay. It is a stain on the AFL that no player has ever felt empowered to do the same."

Panahi argued in favour of bans on smoking – an exception to her opposition to the "nanny state". Feminists were attacked for staging "slut walks" instead of campaigning against genital mutilation. One of her early controversies concerned an attack on teachers threatening industrial action:

"Why, one wonders, do presumably intelligent people study for four years to enter a profession where they find the pay so unacceptable? It's akin to buying a house near an airport, then complaining about aircraft noise... Perhaps we'd attract better quality candidates if existing teachers didn't carry on like a pack of insufferable moaners."

Last year, after a solid seven years of contributing columns and courting the editors of the Herald Sun, Panahi was finally taken on staff.

She had begun, she says, to bring news stories to the paper ("I know a lot of people in this town"), but her main value, she agrees, is as a columnist.

Panahi's social media presence gives the impression of her life being an open book. She tweets pictures of her son, talks about her beloved Mornington Peninsula, posts pictures of her meals and talks about her love of the beach, the local surf lifesaving club and her frequent travels, most recently a cruise around the islands of Indonesia.

Clockwise from top left: Rita's mother Zinat cuts a cake in pre-1979 Iran; Zinat (third from left) pre-revolution with friends; Zinat on horseback pre-revolution; Rita's father James on an Iranian beach with baby Reza and Rita.

Yet those who work with her sense a strong reserve behind the apparent openness, even a loneliness. She has been kind and generous to friends, but some feel she has dropped them when they have outlived their usefulness. To her colleagues, she seems either to not have many friends other than those in the media and sporting world, or to keep the two strictly separate.

She and her parents were hit hard by the death of her only brother a few years ago, after years of struggle with a degenerative condition.

Asked to name those who have mentored her, Panahi makes broad, general statements about the editors and writers at the Herald Sun. She names nobody in particular. The critics with whom she tangles on Twitter speculate about Panahi's rise as some deep News Corporation plot. The truth is more remarkable: she has done it on her own.

Colleague and friend Ellen Whinnett describes Panahi, 39, as "our leading conservative female voice", saying she "articulates a view that I think a number of our readers would agree with”.

“She's also got really great insights into sport, popular culture,” Whinnett says. “She's a single mum juggling parenting and work, and she's an American Iranian Aussie, so I think she's highly representative of Melbourne, Victoria, and of our readership."

Panahi is not always predictable. Along with the standard fare of News Corp columnists – ABC and Fairfax bashing, and boasting about the home team – she is, on some issues, surprisingly socially progressive. She has argued in favour of women who can support their children choosing single motherhood, as she has.

She hates homophobia. She comments on films, on dress standards, on popular television. On climate change, she is not explicitly a denier, but describes many celebrity campaigners for reduced carbon emissions as hysterical hypocrites. Terrorism, she has suggested, is a more pressing concern for most Australians.

Critics see Panahi's rise as a deep News Corporation plot. The truth is more remarkable: she has done it on her own.

On more trivial matters, she once argued for a ban on swimsuits more than 200 metres from the beach. But, increasingly, her defining riff is to defend her adopted country against allegations of racism, while arguing against tolerance for Islam.

People on the inside at the Herald Sun say Panahi has become the go-to woman when the editors want an extreme view expressed.

"She never flinches from controversy," says one of her colleagues. She'll write things over which others would hesitate. And her colleagues remark that she almost never turns down an opportunity for exposure. Panahi is everywhere – on Radio 3AW, on Sky News, on Sunrise.

Rita Panahi claims she is quite prepared to attack "my own side" when the situation calls for it. Asked for an example, she mentions her criticism of former Speaker Bronwyn Bishop's famous helicopter ride.

Her writing is lively, often bellicose and sometimes witty, strong on assertion and short on argument. She articulates a view, rather than convinces. She does not canvass ideas, so much as assert positions. If she has a wider range as a writer, and can engage with nuance and complexity, is yet to be seen. But it could happen. Her talent is impossible to doubt.

One of her friends says: "She is full tilt at making it. I think she figured out at some stage that making it wasn't just about money.

"It's about influence and profile. She is heading for the top."