WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following article contains images of deceased persons.

Khadija Ahmad's life-story is an incredible one: from an Aboriginal girl in country New South Wales who felt shame over her skin-colour, to her discovery of Islam and subsequent conversion, and then her relocation to Syria where she became a mother, her journey could easily span several life-times.

Australia in the 1950s and 60s wasn't an easy place to be Aboriginal. The Australian Government was still forcibly taking children away from their families, and because of this, Ms Ahmad's mother and her needed to move often to evade the authorities.

Life was also difficult because her cultural heritage was unclear. Her mother was Aboriginal and her father was French-Chinese, but she was told she was a "half-caste".

"I was a 'wog' because of my dad," Ms Ahmad told SBS Arabic24.

"I was a black half-caste. I identified as a half caste.... [because that was what] the society labelled me." Growing up in western New South Wales during the 50s and 60s, Ms Ahmad felt keenly aware that she didn't look like a "typical" Aboriginal. Her skin wasn't dark enough. Yet it was still too dark to be considered white.

Growing up in western New South Wales during the 50s and 60s, Ms Ahmad felt keenly aware that she didn't look like a "typical" Aboriginal. Her skin wasn't dark enough. Yet it was still too dark to be considered white.

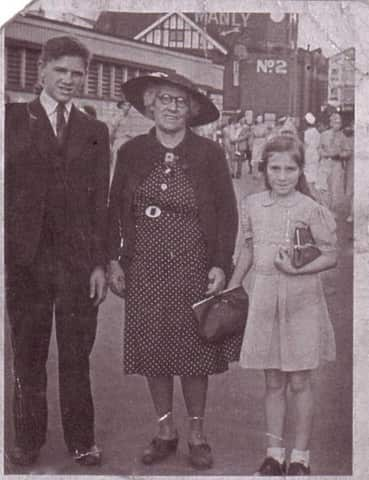

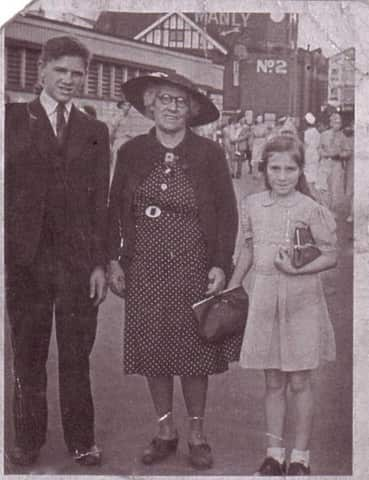

Khadija Ahmad as a young girl with her grandmother and uncle. Source: Supplied

"I was a black half-caste," she said.

"I wasn’t black but I was tanned. I was a dirty dusty-brownish.” So as a teenager, that created confusion for her. Because of her mother, she was given a sense of her culture's spiritual heritage and as she got older she began searching for ways to fulfil this spiritual need.

So as a teenager, that created confusion for her. Because of her mother, she was given a sense of her culture's spiritual heritage and as she got older she began searching for ways to fulfil this spiritual need.

Khadija Ahmad (front row, second from left) as a young girl. "I was darker as a kid" Source: Supplied

“My mother would talk about... [being] connected to the earth and [that] we come from the dirt and we will go back to the dirt," Ms Ahmad said.

"[She would say] 'we are made from something'... She didn't say 'God', that was a word she never used. [She just said] 'something' made us." From an early age she began asking her mother questions about religion, and by the time she was 11 she started visiting different churches to try and feed her spiritual hunger.

From an early age she began asking her mother questions about religion, and by the time she was 11 she started visiting different churches to try and feed her spiritual hunger.

"My mother a few months before she died" Source: Supplied

“I remember at 11 going to Jehovah's Witnesses wanting to learn, and she never stopped me, she just raised an eyebrow," Ms Ahmad told SBS Arabic24.

The young girl visited the churches of different religions for the next decade before, at the age of 21, she discovered Islam. Its beliefs had clicked with her Aboriginal spirituality in a way no other religion had.

“When I found Islam I knew it was what I wanted. This had something to do with my natural instinct," she said, adding that as she got older she better understood why.

"Islam and my spiritual Aboriginality are so the same, and it all makes sense now as an adult.

“In Islam there is oneness, and Aboriginality talks about a oneness, and this oneness is deep inside us and you can’t take it out. And when you die it comes out and travels to the dreamtime.”

Khadija Ahmed Source: Supplied

When she made her first Hajj during her conversion to Islam, she discovered it was forbidden to hurt or harm anything - including nature.

“You can’t break a branch, you can’t hurt anything," she said.

"I always felt nature... could feel and... could hear, and then when I became Muslim, it [became] so clear."

The 60-year-old still recalls that defining realisation of four decades ago with poignant clarity, and remembers thinking: "Oh my God, this all fits together. This is what mum said."

"Mum said that animals [and] trees feel, they sense you. Don’t hurt them,” she said.

"[Aboriginal people] had strict rules, and those rules are very similar to Arab rules."

The Islamic Hajj ritual she undertook also involved travelling to Saudi Arabia. There, she had fallen so love with the city of Madina Munawara she prayed to Allah to marry someone from there.

Less than a year later she met a Syrian man who lived there and accepted his hand in marriage.

The couple had moved back to his homeland and had three of their seven children there.

With children of her own, it was important to Ms Ahmad that they knew about their Aboriginal and Syrian heritage so they didn't experience the same confusion about identity she had felt growing up.

As a result, her seven adult “are very proud about their Aboriginality and their Syrian background,” she said. "I spoke to them about my history, our Aboriginality and how long Aboriginals were there [in Australia] - they weren’t just black people running around naked. They actually had systems and they had social lives and a really strong cultural background," she said.

"I spoke to them about my history, our Aboriginality and how long Aboriginals were there [in Australia] - they weren’t just black people running around naked. They actually had systems and they had social lives and a really strong cultural background," she said.

Source: Supplied

"[Aboriginal people] had strict rules, and those rules are very similar to Arab rules: Eye for an Eye and punishment and birthing [rituals]… [are] very similar. It's just that the structure of the society was different.”

“My skin might get lighter but my DNA is still going to be Aboriginal.”

As a little girl who grew up feeling both confused and shame over her Aboriginal background, NAIDOC week carries a lot of importance to Ms Ahmad.

"My skin might get lighter but my DNA is still going to be Aboriginal," she said

“It’s okay to be Aboriginal now, it's safe to be Aboriginal now and that is really important."

To her NAIDOC week is also an opportunity to show Australia and the world that Aboriginals have not disappeared. And they still have the right to speak and to be heard.

"We are still here... This land wasn’t just here for the white man. It belongs to us. It was ours first," Ms Ahmad said.

“My mother once told me that we are connected to our past, we are connected to our ancestors, and we are connected to our future people...

"She was told [this] by her grandmother who was told by her grandmother. This is our DNA. We can’t take our DNA out.”

Share