Since civil war broke out in South Sudan in late 2013, tens of thousands have been killed and more than two million people have been displaced from their homes. Among the staggering number forced to seek shelter in refugee camps in neighbouring countries, have been thousands of children and teenagers. Many of whom have been left orphaned by the ongoing conflict.

While life is hard for all the children and teenagers living in the crowded refugee camps scattered around Kenya, Sudan, Congo, Ethiopia, and Uganda, girls have the added difficulty of trying to manage menstruation without essential hygiene products.

When they get their periods, girls and women in refugee settlements have no other option but to isolate themselves. Many are even forced to leave their homes to find somewhere to hide while they are menstruating.

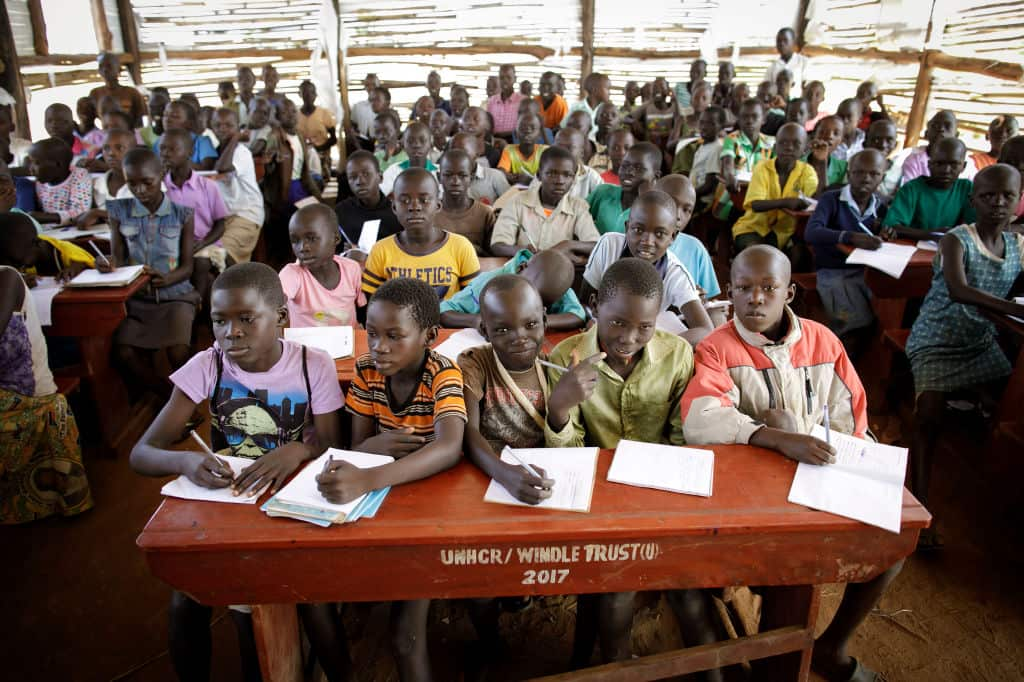

The constant interruption in the girls' and young women's lives has a huge impact on their schooling. Girls without access to sanitary pads miss an average of three months of school every year.

With such a huge chunk of time spent away from the classroom, many girls fall behind their classmates and if they can't catch up they have to drop-out. Girls forced to leave school can sometimes end up marrying and having children while still very young.

Someone who understands all too well how crucial sanitary pads are to girls' futures is Akeer Chut-Deng, a South Sudanese refugee herself whose family was given asylum in Australia when she was a child. In her new home, she embarked on a career as an international model, but it was motherhood which triggered her need to do something for the thousands of young South Sudanese girls still living in refugee camps.

Ms Chut-Deng was born in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan. At a very young age she had to flee home with her family and seek refuge in camps Ethiopia, and then Kenya. She and her family were subsequently granted refugee visas and arrived in Australia more than 20 years ago.

Now living in Toowoomba in Queensland, Ms Chut-Deng hadn't seen the country of her birth in decades when the birth of her daughter brought back memories of the harsh life girls in South Sudan faced.

“When my daughter was born, I asked myself… if this daughter of mine was not born in this free country, what would her life be like in South Sudan?" she told SBS Dinka.

"My daughter, Yar pushed me to do things that I have always wanted to do.”

The young mum and former-model decided to begin the Freedom Pads Project to provide sanitary pads to South Sudanese school girls because, "There's no country on this earth that can develop without women... or women not having a voice."

"We must educate girls and look after them if we want a better country,” she said.

Through social media Ms Chut-Deng advertised her campaign and quickly also created a space for people to talk freely about the health and well-being of girls in war affected areas in South Sudan and the refugee camps.

It was a topic that resonated with the many South Sudanese women who didn't have access to hygiene pads during their teenage years.

By March 2018, the Freedom Pads Project raised enough in donations to travel to Uganda and South Sudan to distribute reusable sanitary pads to girls in refugee camps. It was the first time Ms Chut-Deng had been back since she left as a refugee herself more than 20 years earlier.

A total of 1,500 pads were given to school girls in refugee camps in Uganda and to schools in Juba, South Sudan.

While in Uganda, Ms Chut-Deng heard for herself from a young girl how her monthly periods impacted her life and her education.

"Every month when I am on my period I don’t attend school," the schoolgirl told her.

"[She had] missed out on one of the pads distributions organised by one of the NGOs. As a result, she was trying to buy pads from other girls and nobody would give her their own pads.

"She was missing lessons and had to repeat a class. It was presumed the reason she was repeating for the second time was that she is stupid or limited."

In many of the South Sudanese communities Ms Chut-Deng visited, she discovered that speaking about female menstruation is still incredibly taboo. Through feelings of shame, girls and women had been silenced from speaking about sexual health and well-being.

Even though male school teachers and doctors dominate the education and health sectors, Uganda is still considered progressive in how it values girls' education and health issues. Even on her short visit to schools and refugee settlements, the difference between South Sudanese and Ugandan communities was obvious to Ms Chut-Deng.

“When I went to a refugee camp in Northern Uganda, the feedback was very positive and a lot of the males and teachers in general mentioned the relevance of this project and said: ‘This is a fantastic initiative and we appreciate you. We need the girls to improve their education and your present is a great thing'".

Yet, despite these advances, when it came to giving girls a space to talk freely about their own sexual health and well-being, traditional tropes surrounding gender still held girls and women back.

“One of the things I didn’t like was when I asked the teachers to give me access to senior girls to help me with the pads distribution and also to have a little group session and to talk about menstrual cycle, the response was that ‘they are not intelligent enough,'" Ms Chut-Deng recalled.

"I didn’t like that and I felt offended. How are they not intelligent?”

During her visit to South Sudan's capital city, Juba, Ms Chut-Deng saw for herself how the country's citizens were being pushed further into poverty.

“Out of my experiences in Juba, when we went to pick up pads from the depot, there were a group of people sitting on the side of the road and I noticed an old lady with a rope tied around her stomach," she said.

"I was walking pass her when she said, ‘dear daughter, can you help me with something to buy water?’

"I looked at her and I nearly cried because she looked very frail. I gave her some money but that money didn't solve the [the situation].

Sudan's two decades of war

After 22 years of civil war for independence from Sudan, the Sudanese People's Liberation Movement arrived to power in 2011. The Army fractured along ethnic lines 18 months later when President Salva Kiir, a Dinka, faced a leadership rival in his deputy, Riek Machar, a Nuer. Last year the war spread, drawing in other ethnic groups in west and southern South Sudan.

More than one million children have fled South Sudan because of the conflict, the UN Refugee Agency said in February 2018.

Another 17,000 youngsters are believed to have been recruited as child soldiers.

The fighting has pushed 30 percent of the country's 12 million people to flee their homes.

Despite the crisis, the White House has just announced a review of its assitance programs to South Sudan under the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission.

The United States government has said they need to be sure their "assistance does not contribute to or prolong the conflict, or facilitate predatory or corrupt behavior."

The cut of humanitarian aid would have a significant impact in South Sudan since the United States is the largest donor of humanitarian assistance to the country.