India's media environment is often applauded for its sheer size, but a key question is the quality of information available to its voters – an acutely relevant issue as the country undertakes its general election.

The election, which is itself the world's biggest, is being held in seven phases from 11 April to 19 May, and will see some 900 million voters express not just their consent, but ideally their informed consent, for who should rule over them for the next five years.

These voters derive their information not just from legacy media - around 400 television channels dedicated to news, and nearly 18,000 newspapers - but also from digital-born news platforms, social media and mobile messaging applications.

Around 300 million Indians use Facebook, the largest number for any country, and around 200 million use the Facebook-owned messaging platform WhatsApp.

A Reuters Institute study released on 25 March says that English-speaking Indians are "embracing a mobile-first, platform-dominated media environment", and a white paper from US technology firm Cisco says that the country's smartphone users across languages are expected to double to 829 million by 2022 - up from 404.1 million in 2017.

But more channels don't necessarily mean better information, and since the last election in 2014, India's media environment has witnessed a rise in fake news, deepening polarisation, and changes in the media landscape that have challenged the available diversity of viewpoints.

The rise of fake news

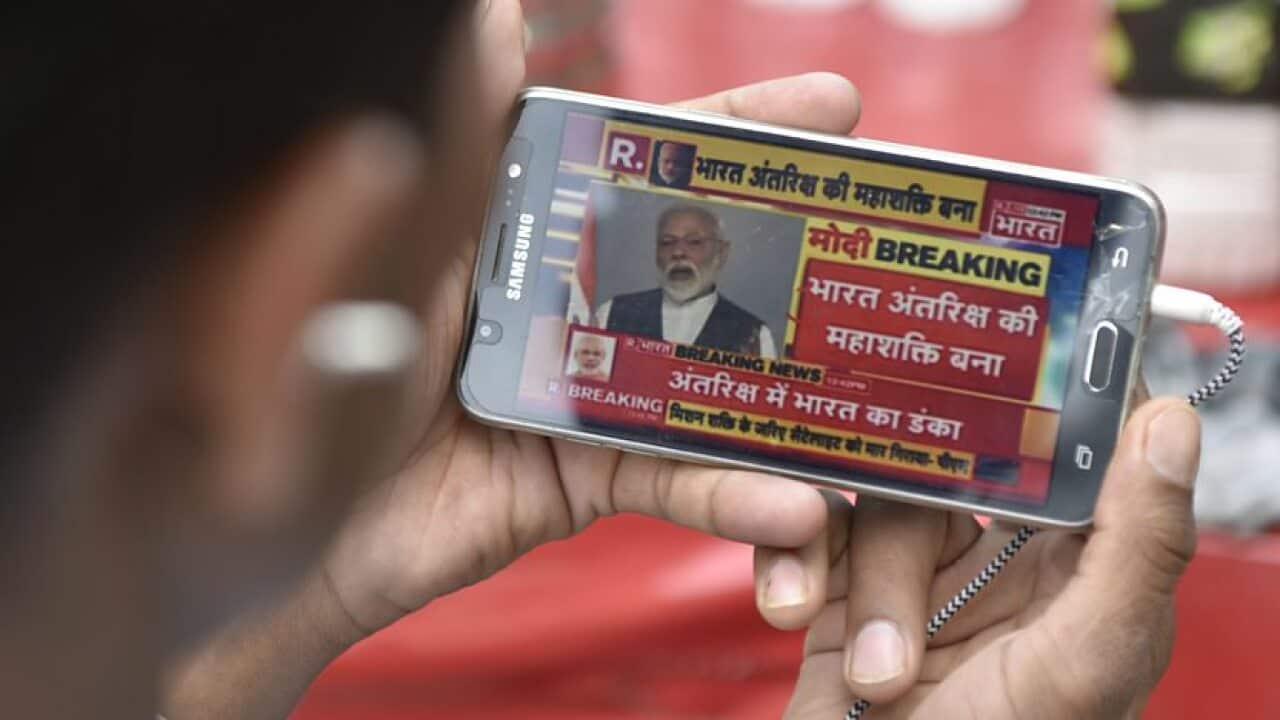

Over the last five years, India has seen a proliferation of falsehoods via WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter and other apps and social media – a Microsoft report in January 2019 said India was the first in 22 countries severely afflicted by fake news, while a BBC study published in November 2018 spoke of a nearly 200-per-cent rise in Indian media reportage on the fake news phenomenon in three years.

The rise doesn't just reflect the state of India's political discourse but has also had tragic human consequences.

Regarding the first, the BBC study asked why ordinary citizens spread fake news despite being concerned about its rise and identified rising "nationalism" as a factor, saying that "facts were less important to some than the emotional desire to bolster national identity".

The paper also suggested that "right-wing networks are much more organised than [those] on the left, pushing nationalistic fake stories further", and that there was "an overlap of fake news sources on Twitter and support networks of Prime Minister Narendra Modi".

Narendra Modi is from the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which, along with other Hindu nationalist organisations, is described as "right-wing".

A 27 January report from the newsletter DisFact found that Modi's personal Twitter-like app "NaMo" is also "plagued by the fake news menace".

The app, which was launched in June 2015 to "receive messages and emails directly from the prime minister", has been downloaded over 10m times and has an average of 1.43 million daily active users, who can post text, images, videos or website links.

"The visible lack of content moderation" makes the app vulnerable to intercommunal hate speech and fake news, the report says.

But aside from politics, India has also seen numerous cases of mob violence triggered by rumours spread over WhatsApp and social media – and legacy media have mostly discussed this aspect, rather than any organised use of fake news by political players.

Between February 2014 and July 2018, at least 31 people have been killed and dozens more injured in such violence in cases verified by the BBC, although the number of reported incidents is higher.

In many instances, false rumours on WhatsApp or other platforms have warned people that there are child abductors in their towns, driving locals to target innocent men who were not known to the community.

What has the response been so far?

Growing public concern, media criticism and an appeal from the Indian authorities have led WhatsApp to take steps such as tagging forwarded messages and limiting the number of forwards to five at a time in India, compared to 20 in other countries.

Since July 2018, WhatsApp has also been running campaigns using online, print, radio and TV advertisements to increase awareness about the dangers of sharing false rumours.

For instance, a WhatsApp ad aired on prime-time television shows a woman who uses the app to stay in touch with her family, but when a relative forwards a fake message, she tells him not to share rumours.

The company has also reportedly banned around 300,000 India-based accounts that show spam-like behaviour.

At the end of 2018, the Indian press reported the government was considering a change to the law that would force Facebook to police WhatsApp for "unlawful" content.This would challenge its use of end-to-end encryption technology, which means a message can only be read by its sender and recipient – but such a move would draw criticism from free-speech advocates who fear it could lead to censorship.

Apart from WhatsApp, India's Election Commission (EC) is coordinating its efforts with technology giants Google, Facebook and Twitter to take down content that violates the body's guidelines.

Further, Twitter's vice-president for global public policy and philanthropy, Colin Crowell, appeared before India's Parliamentary Standing Committee on Information Technology on 25 February to discuss concerns about citizens' rights on the platform.

Additionally, India has seen the rise of media outlets specialising in fact-checking: Alt News, Boom Live, FactChecker, Vishvas.News, Factly and Fact Crescendo are key examples, along with established media such as India Today and The Times of India, and digital outlets such as The Quint, also setting up such initiatives.

In step with this trend, Facebook has partnered with seven third-party fact-checking organisations in India ahead of the election.

Rising nationalism

Another trend seen since 2014 has been the rise of hard-line nationalism among influential sections of the media.

The change can be clearly seen on popular news channels where coverage has become largely characterised by shrill prime-time debates echoing a strongly nationalistic stance, often at the cost of objectivity.

Many channels such as Republic TV, Times Now and several regional news TVs regularly lean to the right (and in support of the government) on major issues that have hit the headlines since 2014.

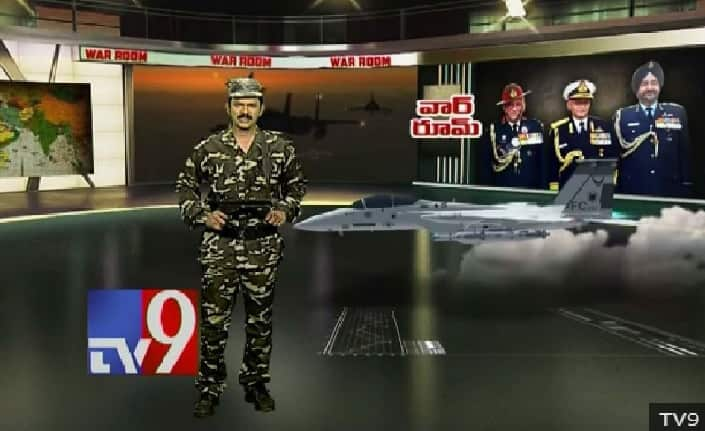

Nationalism on screen reached its frenzied peak in the aftermath of coverage of the suicide attack in Pulwama, Indian-administered Kashmir, in which over 40 soldiers were killed.

A number of channels made direct calls for reprisals and revenge against Pakistan.

Media monitoring website Newslaundry characterised the incendiary coverage across the channels as one led by the "war-mongering news anchor".

Singling out Republic TV's Arnab Goswami (who was earlier the face of Times Now) for leading the pack, the website wrote on 16 February: "Essentially, Goswami has set the template that all of them [other TV news anchors] try and ape."

This nationalistic coverage is marked by the increased use of the word "anti-national" in the media. So much that Goswami dedicated one of his prime-time debates to justify the use of the word "anti-national" for those who, in his opinion, were indulging in "anti-India activities".

Opposition parties and activists, however, say the words "anti-national" and "traitor" are being loosely used in the media to describe anyone holding liberal opinions or views opposed to those held by the right-wing groups.

For example, in a debate on the Indian military's response to the Pulwama attack, Goswami criticised "peaceniks" (those proposing restraint on India's part), telling them to "wake up" and change their ideology.

In April, a spokesman of the Congress Party threw a glass of water on a member of the rival Bharatiya Janata Party during a live debate on a Hindi TV channel. The Congress spokesman was angry over being repeatedly called a "traitor" by his political opponent.

Meanwhile, verbal abuse and threats have also become common on social media, and "liberals", including journalists, are often told by Hindu nationalists on Twitter to "Go to Pakistan".

Senior journalist Barkha Dutt recently said on Twitter that she had received death threats, and obscene messages and pictures on social media following her comments about the harassment of common Kashmiris across India after the Pulwama attack. Dutt was until recently a prominent face on NDTV, considered to be among the few remaining centre-to-left channels, though it is often accused of holding a pro-Congress Party stance.

Amid the changing nature of Indian news, some feel it is wrong to generalise the nature of coverage and blame the BJP government for it.

"If you go around today in 2018 arguing that media was unfettered and free and robust and vibrant in those years, and suddenly things have gone south, now that's just nonsense. There has been media that have been compromised and complicit and silent all through the history of media in India", BJP MP Rajeev Chandrasekhar was quoted as saying by The Washington Post in February 2018. He was earlier on the board of the ARG Outlier Asianet News Private Limited, which runs Republic TV.

The changing ecosystem

These trends have come within a context of a changing media landscape since 2014, particularly with respect to ownership, the rise of digital-only outlets and government action against some media groups.

Regarding ownership, a striking example is that of businessman Mukesh Ambani, the country's richest man who is said to be close to the BJP – a party that gives importance to shaping the media narrative, even as its critics say it refuses to allow space for dissent.

So when Ambani's Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) bought Network 18, one of India's largest media conglomerates in May 2014, commentators such as journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta saw it as a warning sign for the entire media industry.

"It is but natural that questions will be raised as to what this development means for freedom of expression in the world's largest democracy," he wrote, adding that Ambani's takeover could hamper the Network 18 group's freedom to report stories unflattering to him.

He added that "control over the media implies more political clout which, in turn, translates into greater power to influence economic policies and shape public opinion".

Adding to such fears is the fact that most Indian news companies survive on advertisements from big firms, and RIL is the biggest private Indian firm of all – meaning that concerns over editorial independence extend beyond Network 18.

Soon after the Network 18 takeover, almost all of the group's top officials left, including its founders Raghav Bahl and Ritu Kapur, and senior journalists Rajdeep Sardesai and Sagarika Ghose.

Nonetheless, news media remain a thriving industry in India. Over the last five years, a clutch of news websites and channels have come up on both sides of the political spectrum.

The website OpIndia has managed to become one of the country's leading right-of-centre voices in just four years since its launch in December 2014. Another right-wing publication, the 58-year-old Swarajya magazine, re-launched that same year with a new website.

In 2015, veteran journalists Siddharth Varadarajan and Sidharth Bhatia rolled out The Wire, a left-leaning website which runs on a non-profit business model based on donations and offers what it describes as "public-interest journalism".

But the biggest newcomer has been Republic TV, which became the subject of media scrutiny soon after its launch in 2017 because of investments from Rajeev Chandrasekhar, a politician considered close to the BJP.

Chandrasekhar has reportedly broken ties with the channel after formally joining the party in 2018.

Apart from these developments, critics often accuse the BJP-led government of intimidating the press by using the federal investigative agency and tax authorities against media firms.

In June 2017, federal officials raided properties belonging to the owners of NDTV, whose top staff have close ties to the BJP's political rivals, for a loan that the channel had taken nine years ago.

Another case involved The Quint - the website was set up in 2015 by Bahl and Kapur after their departure from Network 18. Three years later, tax officials turned up at The Quint's offices to investigate alleged tax evasion, which the founders described as the "most intrusive ransom".

Some critics, such as Aman Madan writing for The Diplomat, see this as part of a larger pattern, saying that Modi and the BJP have "moved to hijack the country's historically free press".

But Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has denied this, saying instead: "The biggest challenge today is how the media retains its own credibility so that it continues to become a maker of public opinion."

Source: https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk/