The fear of losing your job to a machine is not a new source of anxiety.

Ever since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, people have worried about the impact of technology.

Economist Jim Stanford heads the Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute in Canberra, and he offers a reassuring message: Work is not going to just disappear.

"You still need human beings, even to design and engineer, manufacture, install, operate and maintain the robots. They can't do it without human beings. So any process that involves automation and new machinery does have new work associated with it as well as the jobs that could be displaced, and what we have to do as an economy is a much better job at matching people who are negatively affected by tech change with some of the new opportunities and options that are opened up because of tech change. If we can do that, then, again, people will stop seeing technology as a threat and see it more as an opportunity."

Dr Stanford says technology itself is not the problem.

He says the issue is all about how Australia manages it.

Futurist Ross Dawson says, because some jobs will be created as others are closed, the focus should be on helping workers develop the skills and capabilities which draw on their unique human capabilities so they can do the jobs machines cannot.

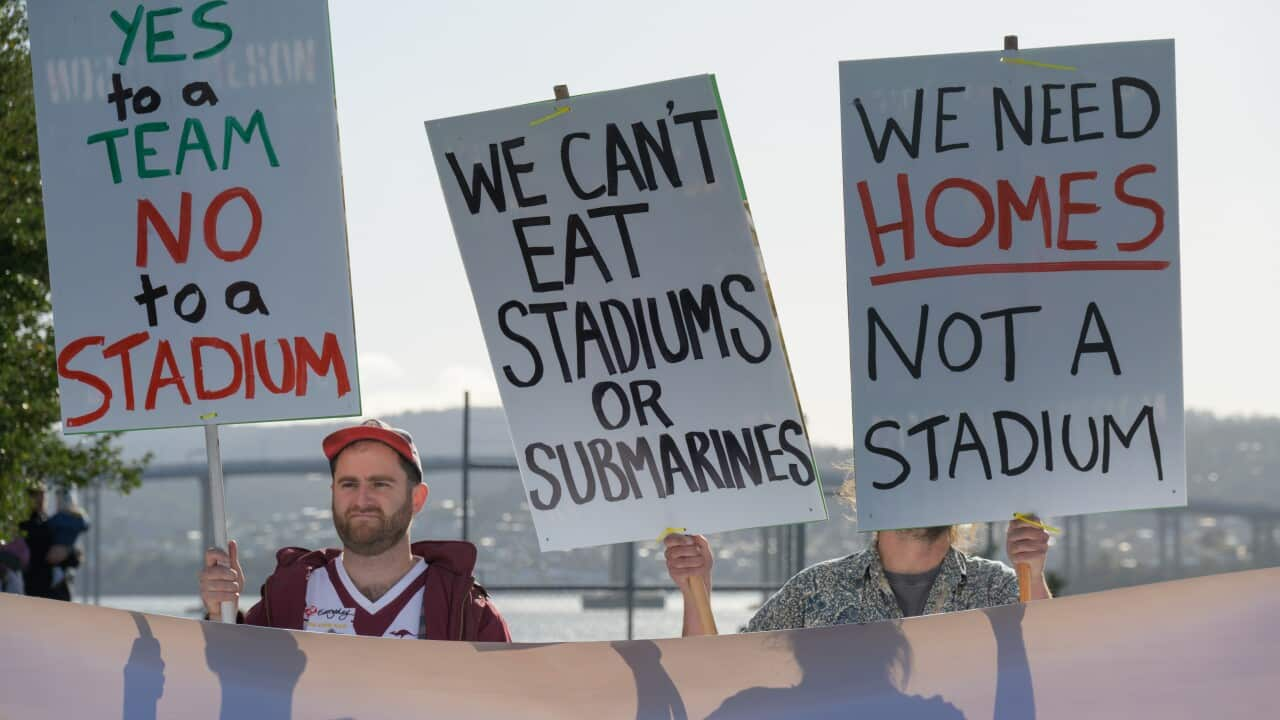

The secretary of the Australian Council of Trade Unions,

Sally McManus, says one straightforward option to protect current and future jobs is to strengthen Australia's workplace laws.

She says a weakening of industrial-relations laws has been detrimental to workers.

"It's allowed employers to just find all these different ways of making a job that used to be a permanent job with full rights into a job that's casual or labour-hire with very few rights. And so that isn't an issue of the economy changing. That's an issue of the laws, or the rights of workers, have changed. And so, absolutely, we can turn around the level of insecure jobs that we've got in our country by simply fixing those broken laws so that, if you're working in a job and you're working there for long enough, you should get all the proper rights and protections that we used to have."

Ms McManus says she would like to see governments work more closely with employers and unions to plan ways of addressing the impact of changing technologies.

Economist Jim Stanford from the Centre for Future Work says South Korea sets a great example of effective collaboration.

"Rather than just giving out tax breaks and subsidies, they actually say, 'We're going to sit down and build, we're going to develop, a world-beating smartphone, or a world-beating automobile, or a world-beating home electronics, and we'll all contribute to that mission.' And the proof is in the pudding,* because, again, the Koreans, like the Europeans, have just really eaten our lunch when it comes to real, deliberate innovation."

The employment website SEEK estimates around half of the existing jobs could be automated using current technology.

Sarah Maccartney says online education will be a key to helping workers upskill to be ready for future job opportunities.