How did we end up in this nightmare?

As an eight-year-old Roza was forced to pray for a long life for Saddam Hussein - now an adult, she describes her life in hell, and her journey to Australia.

Iraqi border with Iran, 1991

As I look out of the car window, I can’t really tell what is happening. People and snow cover the mountains. Where are we? Ruins of a town lie before me. The image is stuck in my mind, we are stuck. Our car cannot move, the traffic is jammed.

My mother who is six months pregnant, my four-year-old brother, Dilan, and I sit in the back seat; my father and a friend in the front.

Still in her work uniform, my mother’s tummy becomes a pillow for Dilan. There’s no food, no clean drinking water and no bathrooms, it’s like a nightmare. Sharing one potato cooked on a small open fire between three adults and two children is all the food we have.

Western media and aid helicopters hover above our heads, watching the exodus of people. From the ground we don’t know who they are, my mother holds tightly to my brother and I. Each time we think, that’s it - any second now we will die.

How did we end up in this nightmare?

All my life so far I’ve lived in wars.

I was born in 1981 into the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq - a war that was never discussed openly. Occasionally I would hear my family and close friends talking. But my efforts to find out more would always result in the same response, “Nothing, you shouldn’t be listening!” At the same time, I was aware of many things through my daily experiences. It was common for the army to be knocking at the door. Sometimes so hard it felt like our house would collapse. They would search for anything, anyone or any sign of opposition to Saddam Hussein and his Ba’athist regime.

By March 1991, with the Gulf War over, US President George Bush told Iraqis to “put Saddam aside”. So they did. Shia in southern Iraq and Kurds in the north rose up against Saddam’s regime.

We were hearing that the south of the country was now no longer under the Ba’athist rule. Every morning my father would wake up and listen to the fearless Kurdish radio.

Roza with her parents on her 3rd birthday.

Roza with her parents on her 3rd birthday.

Then on 12th March, Sulaimaniya, a city one hour from our home in Kirkuk, fell to Kurdish forces. It was unreal! I had thousands of questions to ask my parents about the situation, and this time they explained everything to me! Now I knew now why our people had been suppressed for decades. I was full of hope; I had dreams of a very exciting future.

Kurdish radio; Voice of the People of Kurdistan, was updating listeners around the clock about Kurdish victories, as they took control of more cities and towns in Iraqi Kurdistan.

But on 16th of March, 1991, Ali Hassan Al-Majeed – infamously known as Chemical Ali for his role in the poison gas attack on thousands of people in the Kurdish town of Halabja in 1988 – was put in control of Kirkuk’s security. He rounded up every male aged between 16 and 65 considered to be a security threat. Fortunately, not my father, as had slept at his abandoned workplace outside the city.

No one was allowed to leave their homes. Helicopters and planes controlled the skies and the army guarded every street. Simply looking out of a window could have resulted in being shot at. People were terrified and were running out of food. But at the same time, there was hope. If this was the price they had to pay to be free, then that was okay.

On 21st March, the day of Newroz, the Kurdish new year and national day, my city was finally freed by Kurdish Peshmerga forces – Saddam’s army mostly fled, but this freedom didn’t last long.

Soon things changed.

Regime loyalists went on an offensive to reclaim the cities. We knew we were not safe, we had to leave.

With my aunt, her husband and four kids we left with my family in one car.

Travelling through the central Kirkuk there were dead people everywhere, executed bodies lying in the dirt, bodies taken away had left fresh trails of blood on the ground. Their families rummaging through the dirt trying to scavenge a shoe or any clue to identify loved ones.

Travelling northward with warplanes bombing overhead we contemplated hiding in the bush like many others.

I remember two chickens starting to fly around inside the car. My aunt had secretly brought them along. My mother was angry, “we can’t fit in the car ourselves and you brought your chickens!” As kids, we found it hilarious and couldn’t stop laughing.

We travelled on to Sulaimaniya where we had relatives, and then on towards the mountains that have been the Kurds’ only true friend throughout their history, hence the Kurdish saying “no friends but the mountains.”

All roads leading to the borders of Iran and Turkey were jammed with traffic. By dawn, we were not even close to leaving the city. We saw a family friend and had to make room in the car. Many others with no transport were begging for a ride. That day I experienced what I never believed could happen let alone see with my own eyes.

Some women were giving birth in the back of pick up trucks, in tractors and even on the snow outside. Injured civilians including women and children were lying helplessly on the roadsides. Everyone was running to save their lives.

I was constantly crying in this living nightmare. All we had to eat was a packet of biscuits that ran out very quickly. We collected drinking water from melted snow, under the rain, or from the waterfalls and rivers that ran in this mountainous region. We were all suffering from diarrhea as a result of the lack of clean drinking water.

After a week we arrived at the border town of Penjiwen, which was in ruins. It was one of the 5,000 towns and villages that Saddam’s regime had destroyed in the late 1980s as part of the Anfal Campaign, an ethnic cleansing campaign against the Kurdish people. Nearly 200,000 Kurds lost their lives, over 5,000 died when the regime bombed the town of Halabja and its surroundings with poisonous gasses, the rest simply disappeared.

We spent one day in a ruined house with some friends and were reunited with my father’s family. There I met a girl my age who had lost her parents and was now in the care of our friends. The next morning we continued our miserable journey to the border. Many left their vehicles and started walking to the Iraq-Iran border simply because the traffic was jammed. The enemy was chasing us and time was running out.

Our hopes were shattered when we finally reached the border and found no one was allowed to cross it.

Then, sitting in the car while my father went in search of food, there was a knock on our window – a French journalist wanting an interview. In our eyes this was a very immoral act; the whole world was out there watching us but nothing was being done to help.

After spending several nights in the car, the pain of my mother’s pregnancy became too much. She left us angrily, climbing down the mountain to a Red Cross tent, not sure if the six-month-old baby she was carrying was alive or dead. As my father ran after her, my brother and I were left crying helplessly in the car that had now become our home.

Then, they came with permission for us to cross the border to Iran.

Leaving our car with my father’s family we stood near the Iranian checkpoint where we waited for the Red Cross vehicle to take us to the border town of Meriwan in Kurdistan Province in Iran. We waited in the pouring rain, but the vehicle had not arrived.

“Madam, what are you waiting for?” asked a man in a pickup truck in Kurdish.

My mother told him we were waiting to cross the border and he said, “Well, come with me I’ll take you.”

He was our saviour.

He gave us dates to eat and a plastic sheet to shield us from the rain. He was the kindest man I have ever met and soon picked up everyone who was trying to cross the border.

His name was Sadiq and a Kurd from Kurdistan of Iran, who had come to the border to bring food and clothes to the refugees.

Sadiq and his family saved our lives. We stayed in their home for a month and then moved to a refugee camp. In total, we spent 2 months across the border in Kurdistan of Iran.

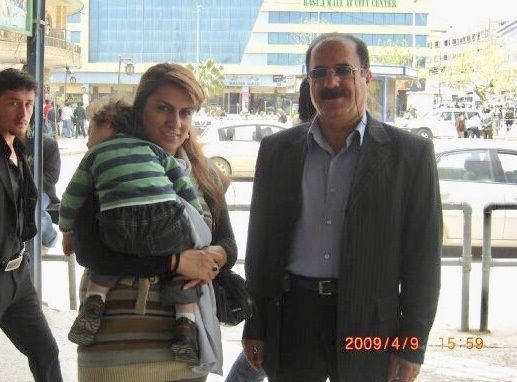

Roza reunited with Sadiq in Sulaimaniya in 2009.

Roza reunited with Sadiq in Sulaimaniya in 2009.

Then, we heard that civilians were slowly trickling back to their homes. By that time it was spring; the snow had melted and the journey back to Sulaimaniya now took us four hours. It had previously taken us 14 days. The mountains were green and full of colour with the newly bloomed wild spring flowers.

Iraqi Kurdistan was safe and under Kurdish control but Kirkuk was scarred by the effects of Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship. As we entered the city, the smell of blood from the dead was still prevalent and the city was still mostly empty. Hardly any of my family had returned yet. We visited my mother’s oldest sister who had just returned from Iran. Their three-storey house had been looted, not even the family photo album was left.

It had been Saddam’s plan to destroy the whole city, but the plans had stopped when the Kurdish leaders agreed to negotiate with him. Slowly the city was returning to its normal life.

On June 12, 1991, my sister Batin was born and we remained in Kirkuk for another three years.

However, the city was not the same - we could no longer own our shop or our house if we did not change our ethnicity to Arabic. Money no longer meant anything. People simply couldn’t find food to buy in the markets due to economic sanctions. We were even being forced to change our names as they were Kurdish names.

So, in 1994 we left the country and travelled to Turkey where we spent two very long years. In Ankara, we experienced racism towards Kurds - to some degree, the Turkish treatment towards the 25 million or so Kurds was worse than Saddam’s treatment.

Our journey continued when in 1996, through the UN in Turkey, we were approved humanitarian visas and arrived in Brisbane to start new lives.

I was 15 and had to learn English. Now I’m lucky enough to have accomplished three university degrees. Since arriving in Australia, only twice had I wished that I was home in Kurdistan. That was when I lost both of my beloved grandmothers.

Roza's brother Dilan and sister Batin in 1997, a year after arriving in Australia.

Roza's brother Dilan and sister Batin in 1997, a year after arriving in Australia.

As I watched Saddam’s statue fall in Baghdad in 2003 and later in Kirkuk, and the allies uncovering decades of crimes against humanity, I never imagined this would happen during my lifetime.

My family and I were able to revisit Iraqi Kurdistan in 2004. We were told stories of unimaginable harsh times in Kirkuk under the brutal Baathist rule since we left.

Almost 30 years later, and now that Saddam and his men are long gone, the fate of Kirkuk and its people still remains undecided.

I cannot imagine what my life would’ve been like if I had not left Kirkuk. I would have gone through at least three more wars. While the wars continue to rage in my homeland so very often, I battled another war inside me. Constantly worrying and dying to know what was happening to my family in Iraqi Kurdistan.

*This article was originally written in 2003 at the start of the war on Iraq which toppled Saddam Husain.