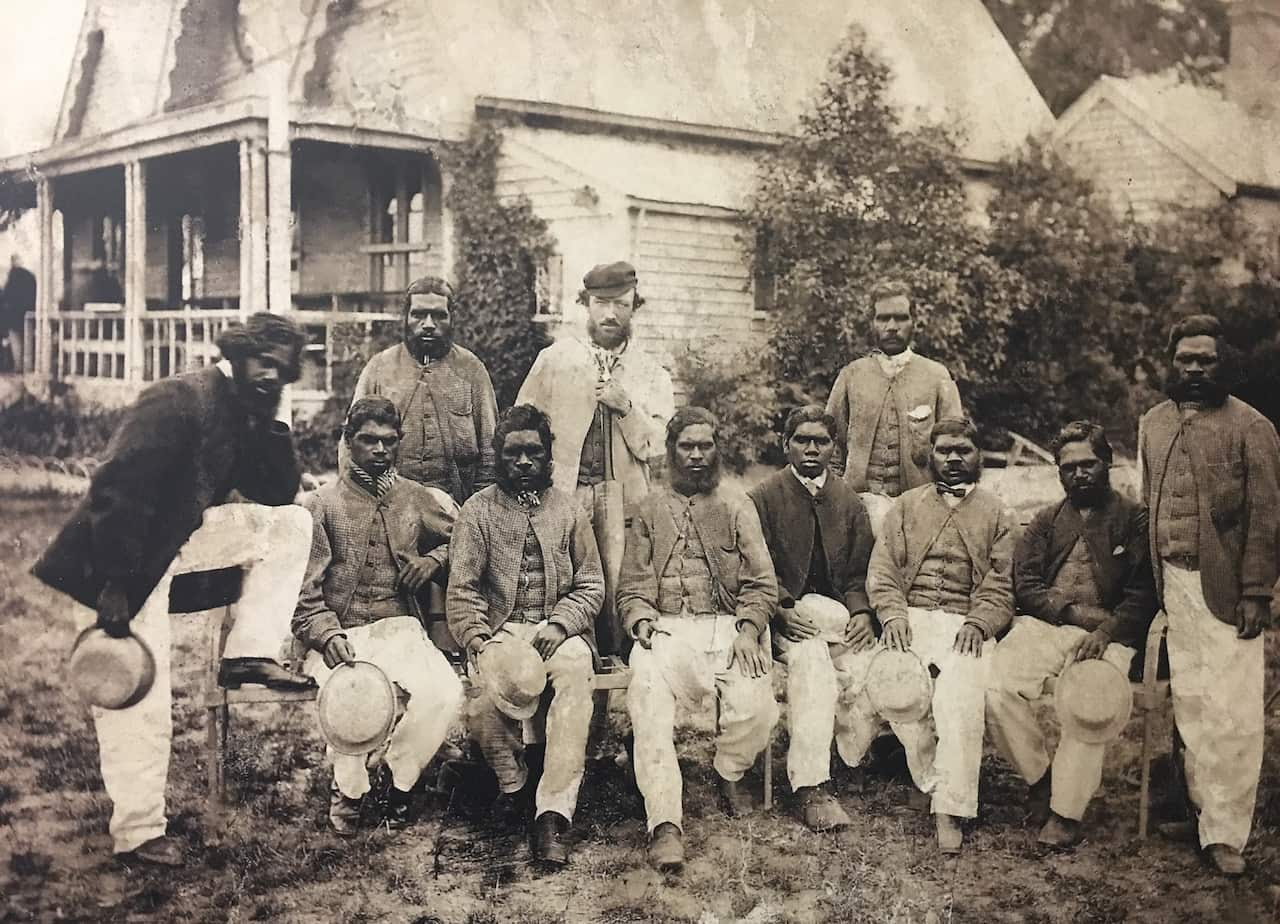

Gunditjmara woman Vicki Couzens grew up hearing stories about her great-grandfather, James Couzens and his brother John Couzens’ cricketing prowess. The brothers were part of the cricket team that represented Australia in its first-ever overseas tournament in 1868, nearly a decade before the first official Test match between Australia and England.

“Growing up, that was our family story about the cricketers and the cricket team and just knowing that the first cricketers from Australia were our mob,” she says.

The Couzens brothers were among the 13 Indigenous Wotjobaluk, Gunditjmara and Jardwadjali men from the Western districts of Victoria who toured England and played 47 games.

The men learned the game on cattle stations owned by English, Irish and Scottish, and began playing cricket for recreation.

It’s such an amazing story of resilience and triumph, but it’s also a story of tragedy and discrimination.

Josie Sangster of Harrow Discovery Centre says their natural athleticism made them excellent cricketers.

“[They] sometimes were just in a spot where the ball would be hit and they just casually picked the ball up and returned it to the stumps but with a speed and an accuracy that was exemplary and a lot of people that were part of this game would stand up and notice,” she says.

“Their natural hand-eye coordination and innate athletic skills applied to the game of cricket made them very good cricketers; it was a natural ability which led them to be amazing cricketers.”

English cricketer Charles Lawrence who began coaching the team, realised the potential of the men and organised the team's tour of England. However, the Board of Protection for the Aboriginal People refused them permission to travel because the voyage was deemed dangerous for the men.

Mark Greenwood, the author of the book Boomerang and Bat: The Story of the Real First Eleven, says the men decided to smuggle themselves out of the country.

“They packed their gear up and headed off to Queenscliff and smuggled themselves out onto a boat, and for most of the players, I assume, from Western Victoria they had never been on a boat, and they were sailing around the world for three months,” he told NITV Radio.

“And they arrived in England and when they did they weren’t the indigenous cricketers, they were Australians.”

Boomerang and the bat

Playing 47 matches against intermediate-level amateur teams there, the team won 14 games and drew 19.

The first Australian sporting team to ever represent this nation was an all-Indigenous cricket team which is a pretty sensational thing to consider in thinking about how cricket is celebrated in our country, and they were the first.

Though the players wore whites while playing at home, they decided to go with bright military green shirts with a coloured sash across and white trousers, on the tour. At the back of the shirts, they had a silver boomerang and a bat.

Between the innings, the men also performed their traditional sports, displaying a range of skills, including throwing boomerang and spear, dodging the cricket ball thrown by spectators, using a shield and club etc.

A story of “resilience and triumph” and “tragedy and discrimination.”

After their return to Australia, most of them resumed their life on cattle stations. However, Johnny Mullagh, who was the star performer during the tour, continued to play the game. He played for Victoria, including against England when the team visited Australia in 1879.

Cricket Australia’s manager of diversity and inclusion, Adam Cassidy says it’s important to talk about this story.

“It’s such an amazing story of resilience and triumph, but it’s also a story of tragedy and discrimination. I think areas of the story need to be talked about.”

To honour Johnny Mullagh, Cricket Australia will present the first Mullagh Medal to the player of the 2020 Boxing Day Test match.

“That will be the first true recognition to the best player in that team Unaararimin (Johnny Mullagh), and we are actually recreating the original belt buckle from that tour, and that will be the medal,” says Adam Cassidy, Diversity and Inclusion Manager at Cricket Australia.

Mr Cassidy concedes that the organisation hasn’t done enough in the past about the issues of racism and a lack of inclusion in the sport.

“We’ve had a number of issues, and it would be naïve to think that we know about all the issues and I don’t think any sport knows how big the racism wound is across the game particularly at the grassroots level. So, having these conversations is a really good start,” he says.

On the NAIDOC weekend, Cricket Australia is holding a Reconciliation Round across all clubs in Australia, encouraging players to form barefoot circles as a sign of acknowledgment and connection to country. It has also started an online panel series ‘Cricket Connecting Country’.