The Rabbit-proof fence is the world’s longest fence - at roughly 2,400 kms long, it runs from south to north in Western Australia and was built to keep rabbits and other vermin out of Western Australia.

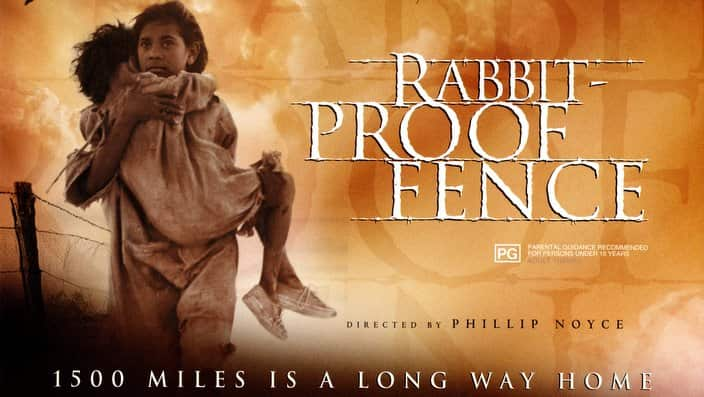

The fence was also made famous as a way home for three little Aboriginal girls, Mollie, Gracie and Daisy. The film 'Rabbit-Proof Fence' is loosely based on the true story of three girls who were members of the Stolen Generation.

"Mollie Gracie and Daisy are three of the most amazing Australian women to have ever lived," Sarah Hyde tells SBS Norwegian.

Taken from their mother by the authorities in 1931, they were placed on a rural settlement and internment camp near Perth but instead escaped and made the remarkable journey all the way back home on foot through the desert to their community at Jigalong - 2,400kms away. They followed the path of the world's longest fence for guidance and made the journey in just nine weeks, all the while being trailed by the authorities.

On a personal mission in the name of reconciliation, Hyde decided to walk in the footsteps of Mollie, Gracie and Daisy along the rabbit-proof fence.

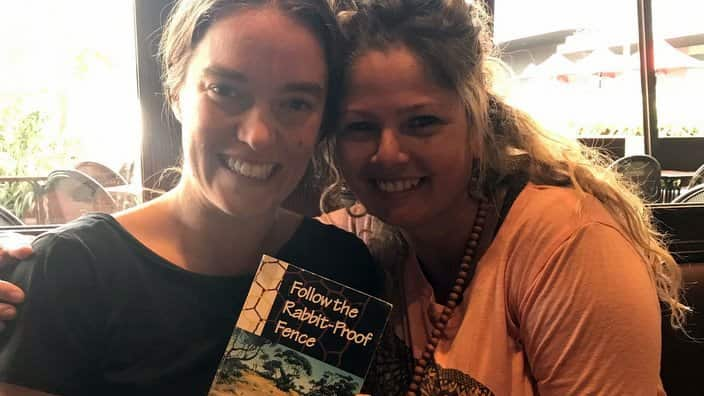

She explains the idea came to her as a perfect storm of a number of events. She was looking for inspiration about what her next adventure could be, she met family members of Mollie, Daisy and Gracie, and she had bought the book about their story and realised it wasn’t called ‘Rabbit-Proof Fence’ as the film, but in fact it was more of a directive: ‘Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence’. So that's what Sarah decided to do.

As she explains, "This walk is about women connecting with themselves and with each other, together, as they walk this significant story in Australia’s history."

"Following the rabbit-proof fence has led to conversation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women about what respect, culture, permission, language and Australia means to each of us."

The moment she saw that title of the she knew, this was her adventure and started planning.

When not out following the Rabbit-proof-fence, Sarah works as a speech pathologist in Sydney University and has lived and worked in the Australian outback including Alice Springs and the Pilbara. Sarah has been involved with the Grandmothers Against Removals and is a member of Desert Discovery, through which she spent five weeks in the western deserts learning about Indigenous science and tracking from the women Rangers of Kiwirrkurra, Australia's most remote community. Sarah is also learning Pintupi-Luritja and more recently, Mardu.

Sarah says, "the walk was never about a physical adventure."

She's never done an adventure like this before but are genuinely passionate about Aboriginal affairs and want to increase awareness.

"It’s not 'my walk,'" she says. "It’s always been about community understanding, listening and learning and connecting with the land the Australian country that unites us."

To raise awareness for the reconciliation she uses the walk to reach out to many communities, like schools, guides and scouts.

The walk presents a great opportunity to come and visit and through talking about the walk and engaging in conversation she raises awareness.

She tells about one scout group she went to see and they were wondering how she would get her cart over the fence.

One realisation she came to when thinking about her own place in today’s Australia is defining herself as a woman of colonial descent or first fleet heritage

They brainstormed some ideas together, and tested them out. After the walk she will get back in touch to let them know how it went, another way to keep the conversation going.

To Sarah, reconciliation is a conversation and sharing stories to understand another person's experiences and how these experiences have changed a person’s life.

"Language is important for reconciliation," explains Sarah.

And she says it is "important to use a respectful language."

One realisation she came to when thinking about her own place in today’s Australia, is defining herself as a woman of colonial descent - or 'First Fleet' heritage. Her great, great, great, great grandfather was the third governor of New South Wales

She explains that "using language in this way is important to me to define who I am in Australia today."

"My family has only been in Australia for about 200 years - while the traditional custodians of the land have been here for thousands and thousands of years."

Sarah says it is important to understand who she is and where she is from.

To prepare for her journey, Sarah has spent days mapping the course, been on reconnaissance trips, undertaken a survival course and done a lot of physical training.

Having a clear north has been important in planning as it made it easy to assess if things was going to help the walk or not and hence prioritise what needed to be done.

She has also enlisted the help of friends and is currently managing a team of more than 20 people helping her out.

Sarah also explains that having been a scout has been a long term preparation for daring to take on such an adventure.

Asked before she started the trip, she insisted she was ready.

Reflecting on her own walk Sarah thinks back onto Mollie, Daisy and Gracie’s journey. She says "they were just kids doing this."

"They didn't have the chance to plan and prepare for their journey like I do."

They took a chance and went, and used skills that their culture had taught them about the earth to survive their journey back to their families.

"I didn’t need to be afraid at all - as they are some of the most beautiful people."

Sarah says "there is a difference between permit and permission."

She explains that to cross certain lands and areas she needed a range of different permits.

More importantly to her was to get permission from the families of Molly, Gracie and Daisy to retrace their steps, as it wasn’t all that long ago since they did the walk.

She was very nervous about approaching the families and says she wrote seven different letters to the family but didn’t send any of them.

In the end she explains, "I didn’t need to be afraid at all - as they are some of the most beautiful people."

Shortly before she started the journey along the rabbit proof fence she met Shari Pilkington for the first time - the granddaughter of the acclaimed Australian author Doris Pilkington Garimara, who penned the book. She was given a first edition of the book that was gifted to Shari from her grandmother. It had the following greeting written inside:

"To Shari (and her children), With all my love and good wishes for good health and happiness. Your grandmother and great grandmother, Doris Pilkington."

Sarah was asked to walk the book along the rabbit proof fence in the footsteps Mollie, Daisy and Gracie and she sees this as the ultimate blessing of her journey.

You can follow Sarah's journey on www.rabbitprooffencewalk.org and on her Facebook page.

Listen to her whole story on the podcast on the top of the page.