Highlights

- Hours before its expiry on 14 July, Department of Home Affairs extends humanitarian visa program for displaced Ukrainians to 31 July

- Since February, Australia has granted over 8,000 visas to Ukrainians after Russia’s military invasion; over 3,200 visa holders already in Australia

- Ukrainian community remain dissatisfied with extension, loses hope of bringing relatives to Australia

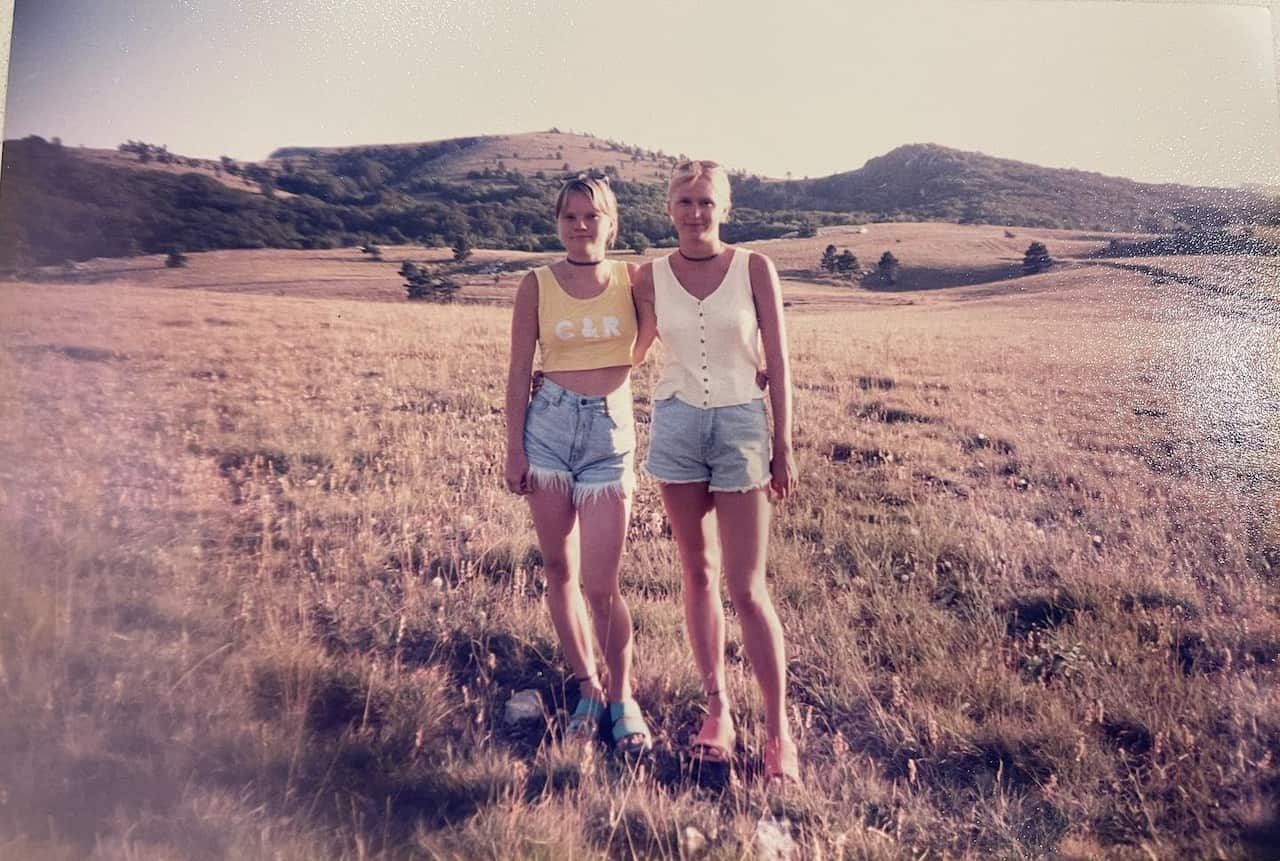

Sydney resident Nataliia Poloziuk lost her sister Irina, who lived in Dnipro, to one of many Russian rockets pounding Ukraine since the war started earlier this year.

She wants the surviving members of her family to come to the safety of Australia but given the Australian government’s deadline for humanitarian visa applications, families like Mrs Poloziuk’s may not have much to hope for.

The deadline for the temporary three-year humanitarian visa was extended hours before its expiry scheduled for 11.59 pm on 14 July.

Immigration Minister Andrew Giles issued a media release on 14 July to announce the deadline had been extended to 31 July. When it was launched, the expiry date of this visa program was 30 June.

"It also became apparent that the initial 30 June expiry date, as set by the previous government, had not been communicated to the Ukrainian Australian community," he stated.

I am extending the deadline until July 31 for all Ukrainian nationals, and their immediate family members, to allow those who were not aware of a deadline time to make arrangements to accept their offer

In order to apply for a humanitarian visa the applicants must be present in Australia at the time of the application, which means that Ukrainian nationals now have until the end of this month to leave Ukraine and reach Australia.

They can also arrive after the deadline but that will be on tourist visas, which means they won’t have access to Medicare, rental assistance or working rights. This means they will be dependent on help for basic necessities.

Talking to SBS Russian, Mrs Poloziuk describes the emotional toll the first announcement about the deadline had taken on her personally, and those who have lost loved ones in Ukraine.

She says that while today's announcement of an additional two weeks has given hope to many Ukrainians, it will make little difference for her family as they will not be able to arrange their travel in the next two weeks.

This news was another blow for me

"We consulted a migration agent if any other refugee visa might be available, but were told that Ukrainians weren't eligible for that type of visa ,” Mrs Poloziuk says.

Loss of family, loss of hope

On the morning of June 28, Ms Poloziuk, a finance supervisor, habitually reached for her phone to check the news from her home country, Ukraine, where all her close relatives live.

In recent months, the news from the part of the world she left behind, have almost always been gut-wrenching because of the continuous war there. But that morning, she woke up to the most terrible news that came with her mother’s text message.

“The first message I saw on Viber was from my mother. She wrote: ‘Natasha, a shell hit Irina’s office, we are going there. I don’t know if she is alive or not. She doesn’t pick up the phone. Probably not alive’,” Mrs Poloziuk tells SBS Russian as she recalls the events of that horrific morning.

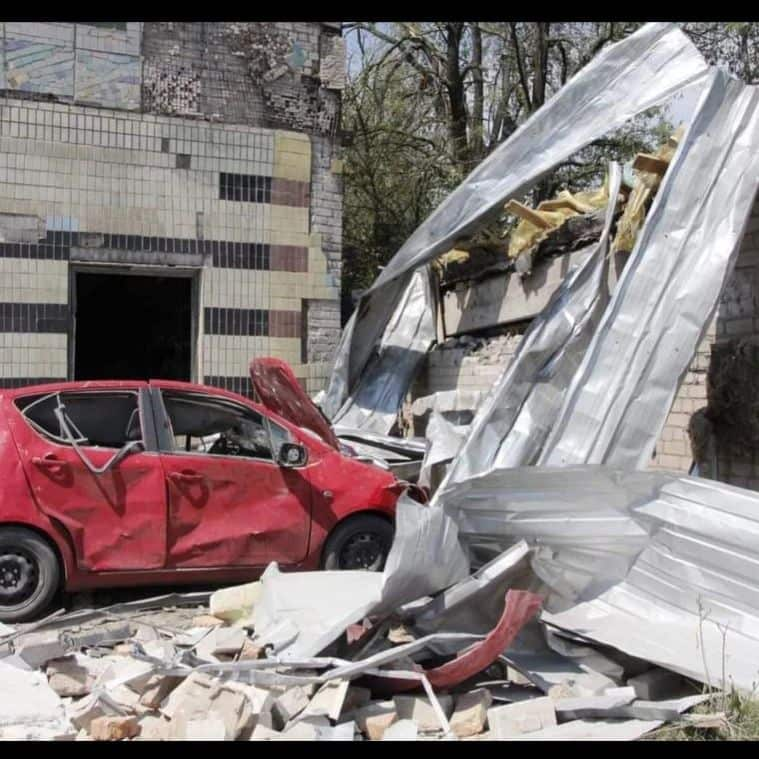

She says that it was already night in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, where the tragic incident had happened around 4 pm the day before. The search operation was still on and they found only fragments of the body of a man, the director of that company where Mrs Poloziuk’s sister worked. But Irina remained missing.

She recollects how she spent the next few hours giving hope not only to herself but also to her mother by talking about cases where people had survived under rubble.

“Several hours passed and my mum sent another text message: ‘That’s it, they recovered her body’. I immediately called her.

But what can you say to a mother whose child has been killed?

"I’m on the other side of the earth. I left my parents’ home early and moved to Australia. While my younger sister was with our mother all her life, they lived together,” she said.

‘Terrible kaleidoscope of events’

Mrs Poloziuk describes what happened next as “a terrible kaleidoscope of events”, with people writing and calling her to express their condolences which, she says, was very difficult to hear because she couldn’t believe that her little sister had died.

“When my cousin sent me photos from the site [of her death], I realised that there was practically no chance for her to survive.

“On that day, it was reported that six rockets were fired at the Dnepropetrovsk region, three of them at Dnipro. Two were shot down. My sister and her director became the first victims to be killed by a missile strike in Dnipro. All the local media wrote about them,” she adds.

Dnipro, as Mrs Poloziuk explains, was considered a relatively safe city. So, her relatives were in no hurry to leave. Irina worked as an accountant and was the main breadwinner in the family. She had a 13-year-old daughter.

“I didn’t push them to leave, I just told them there were options.

“I got a tourist visa for my mum at the very beginning of the war. My dad said that he wouldn’t go anywhere, because he was old and had all his relatives in Ukraine.

“Mum said she wouldn’t go anywhere without my sister and my sister said she wouldn’t leave without her husband, who was prohibited to leave Ukraine under martial law,” says Mrs Poloziuk as she talks about her close-knit family.

After the death of her sister, she again asked her mother if she would come to Australia. This time, she said that she wouldn’t mind, but first she needed to deal with her daughter’s funeral and all the paperwork.

Over 8,000 visas granted to Ukrainians

A spokesperson from the Department of Home Affairs told SBS Russian that since 23 February, the Australian government has granted over 8,000, mostly temporary, visas to Ukrainians in Ukraine and hundreds more to Ukrainians elsewhere, who were forced to flee from Russia’s military invasion. Over 3,200 of these visa holders have arrived in Australia since 23 February.

The department promised to continue to progress visa applications from Ukrainian nationals as a priority, particularly for those with “a strong, personal connection to Australia”.

The spokesperson also told SBS Russian that Ukrainian nationals who have arrived on a temporary visa, and wish to extend their stay in Australia, can seek information about visa options from the Department of Home Affairs.

The Australian government will not require these people to return to Ukraine under the current circumstances.

‘Now, I feel bad I have Russian roots’

Nataliia tells that her mum became an orphan at the age of 14 and grew up in her aunt’s family in Russia, along with her cousin. Both families always stayed in touch. When the war began, she was expecting words of support and sympathy from them but didn’t receive any.

“I was waiting for her [cousin] to check on my parents about what was happening. There were zero questions. It was not at all incomprehensible to me, but my mother told me to leave them (Russian relatives) alone as they had their own lives to lead and everything was fine there. But after some time, I decided to write a message to my cousin to find out her position,” Mrs Poloziuk says.

Her cousin avoided using the word “war” and clearly gave the impression of being “undecided” about the situation.

“I don’t understand these “undecided” people at all. How can you be undecided when people die every day?” Mrs Poloziuk asks.

On the day of her sister’s death, she wrote again to her cousin in Russia:

Do you understand that the cause of her death is your country?

“In response, she [cousin] began to write that Bandera and nationalists were to blame. To be honest, when I hear all this nonsense about Bandera, I just can’t stand it. In any country, there are some extreme movements, but they have never prevailed in Ukraine,” she adds.

“My mother is Russian. My maternal relatives live in Russia while my paternal relatives live in Ukraine. In the family, we always spoke Russian. I don’t associate the Russian language [only] with Russia. This is my native language, in which my mum sang lullabies to me and read fairy tales,” she says talking about her familial ties with Russia and its language despite the military attacks.

After the death of her sister Irina, their relatives in Russia offered Mrs Poloziuk’s mother to join them. But she says she no longer wanted to have anything to do with that side of her family. The “Russian” part of her, which she always appreciated and owned in herself, now feels differently.

I had always been very loyal towards Russia, but my loyalty ended at this point.

"Now, I feel bad that I have some Russian roots,” Mrs Poloziuk adds.

Asked if it is possible in the foreseeable future to restore relations between Russians and Ukrainians, she gives a hard no.

“The restoration of relations between Russians and Ukrainians will definitely not happen during my lifetime and is unlikely to happen during the lifetime of my children. Perhaps later, as was the case with the Second World War, there will be some changes, but I will not see it in my lifetime,” she concludes.