Like many of the traditional languages which became extinct since 1788, the Kaurna (pronounced as “gar-na”) language of the Adelaide Plains was last spoken as an everyday language in the 1860s.

After hibernating for over a century, the language was brought back to life in the late 1980s when a few Elders, community members and a linguist decided to team up to restore the language.

Kaurna and Narrunga (pronounced as “na-roong-ga”) man Vincent ‘Jack’ Buckskin was one of the first students to relearn the language.

“My mother’s generation didn't get an opportunity to speak it or utilise it because she was the first generation that grew off with the missions and her father didn't have the opportunity to speak it and if he did it he was punished for it because he lived on the missions. For me, it’s a massive spiritual connection and gateway to our culture but i want to be able to speak it and utilise it today because my generation is the first generation to be able to utilise language freely.”

Jack is currently one of five fluent speakers of the Kaurna language.

“Some are more advanced than others. Some of those are young kids that have worked with us too that I’ve worked with since they were year 8. Now they’re working alongside me on the journey of language revitalisation but we get around to lots of schools just give them tasters so small group but it’s starting to make traction as an everyday language as well now.”

Jack is teaching Kaurna language to people of all ages, including his mother.

“Yeah it’s hard teaching mum she’s probably the hardest student I've had because you don't tell your mom what to do and she’ll tell me what to do. So a lot of those older people in the older generation are just going well we’ll learn the basics just to get by but the younger kids will learn and take off with it.”

Professor Jane Simpson is the deputy director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language at Australian National University.

She says Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities often go through an arduous process to piece together and restore a lost language.

“It is a hard job restoring a language so we have so many things that we need to talk about and we need to talk fairly fast and communicate ideas quickly so to do that with a language where you only got 200 words recorded that’s really tough.”

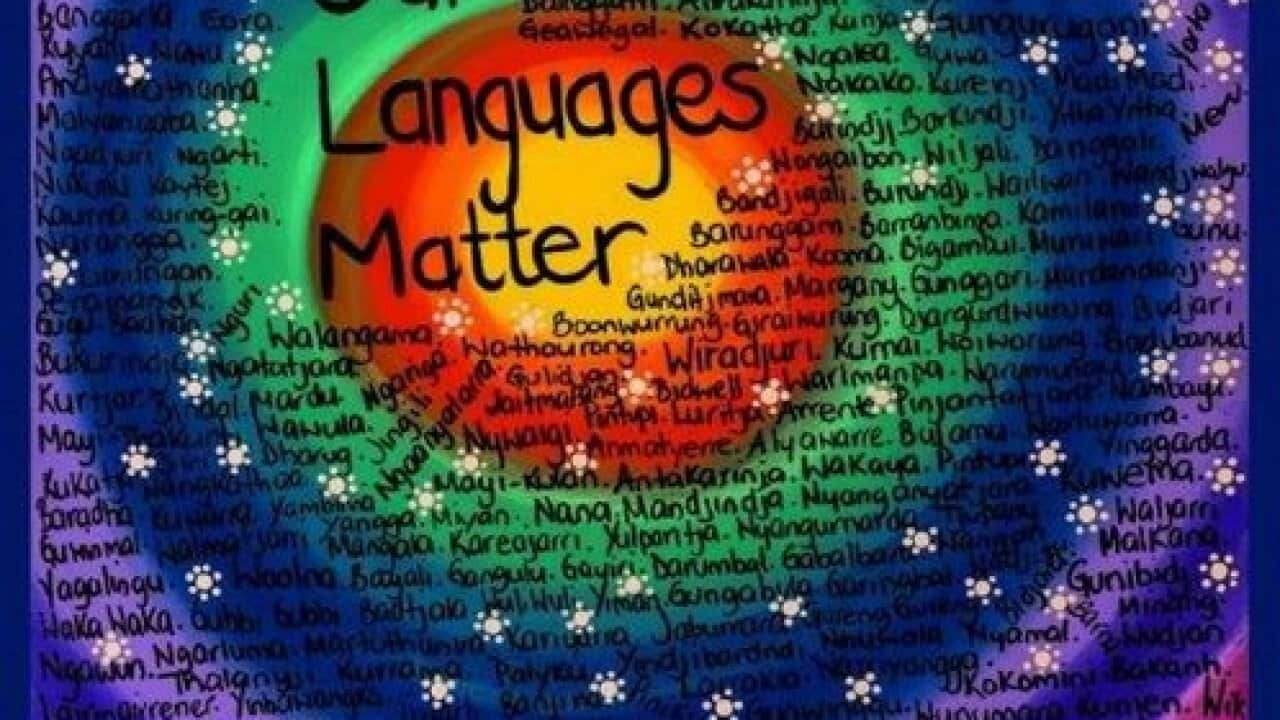

Professor Simpson says successful examples of communities reclaiming their language heritage by using old written sources include the Ngunawal (pronounced as “ngu-na-wowl”) language in the Australian Capital Territory, the Wiradjuri (pronounced as “wi-ra-jer-ree”) and Gamilaraay (pronounced as “gir-miller-rai”) languages in regional New South Wales.

“Probably the best example is Kaurna which was recorded by missionaries in the early 1840s and they provided a dictionary and a grammar and some sentences and a couple of songs and now there are Kaurna people like Jack Buckskin who speak Kaurna fluently and who've been raising families to try to speak Kaurna.”

One of the most spoken Indigenous languages in Australia is the Yolŋu Matha (pronounced as “yoln-ngu-ma-tha”), a term for the 40 Yolŋu (pronounced as “yoln-ngu”) languages spoken across northeast Arnhem Land where the traditional culture has stayed strong.

Miriam Yirrininba (pronounced as “Yi-ri-niin-ba”) Dhurrkay (pronounced as “Dor-gie”), also known as Yinin (pronounced “Yee-nin”), is a proud Wangurri (pronounced “Won-goo-ri”) woman from Dhalinybuy (pronounced as “Da-leen-booey”) homeland.

She teaches the Yolŋu studies course at Charles Darwin University.

The interview is conducted in her native language Dhangu (pronounced as “dthan-ngu”) with translations from her colleague Sylvia Ŋulpinditj (pronounced as “ngool-pin-dee-chi”).

Yinin sees her mission as teaching the new generation to speak their mother tongue and learn their roots.

“And where it is linking, where the idea of using language links to people, from people to people speaking in different dialects but still understanding when it comes to ceremonies and that is what is making us together one hopefully strong.”

Yinin says songlines, which are songs and stories of a journey made during the Dreamtime, are an important tool for language teaching.

“We can understand and clearly hear language in different dialects cos of different songlines and we know of it. What we need to do, how we need to dance but young people they don't have the intention and interest to learn but it is there it was always here.”

Professor Jane Simpson says it’s important for all Australians to embrace Indigenous languages as they mean more than our shared heritage.

“But they are specifically part of the heritage of Indigenous Australians and the wellbeing of many people is bound up with recognition of their language and their language rights and support for them communicating in both their traditional language and in English and at the moment we've got a situation where people don't feel particularly valued. Their languages aren’t valued so that results in social disharmony.”

With the latest Census showing only 1 in 10 Indigenous Australians speak an Indigenous language, Jack says the languages can really strengthen with the support of all Australians.

“Our languages are local to our areas and specific to those areas for all people to be able to utilise it, you know as like the old saying goes, ‘when in Rome, do what the Romans do’, and our languages are unique to our country. One of the old rules is to speak the language on the country you’re on and Aboriginal people knew that, Aboriginal people do that. Now we’re all about teaching the non-Aboriginal people to embrace and utilise those rules as well.”

He suggests perhaps the first step is to start with learning a simple greeting in Kaurna.

“One of the basic ones that we teach a lot of non-Aboriginal people is nee-da-no-mee means ‘are you good?’. I’s like a contemporary greeting it’s not how aboriginal people greet each other we’ve sort of created these new phrases for people and i guess non-aboriginal people how they speak today. But traditional greeting for us is wan-ti-nii-na where are you going? Cos everybody’s obviously busy and keeping themselves occupied so we don't really care how you feel. It’s not how we greet each other but we wanna know what you're going.”

Share