COMMENT

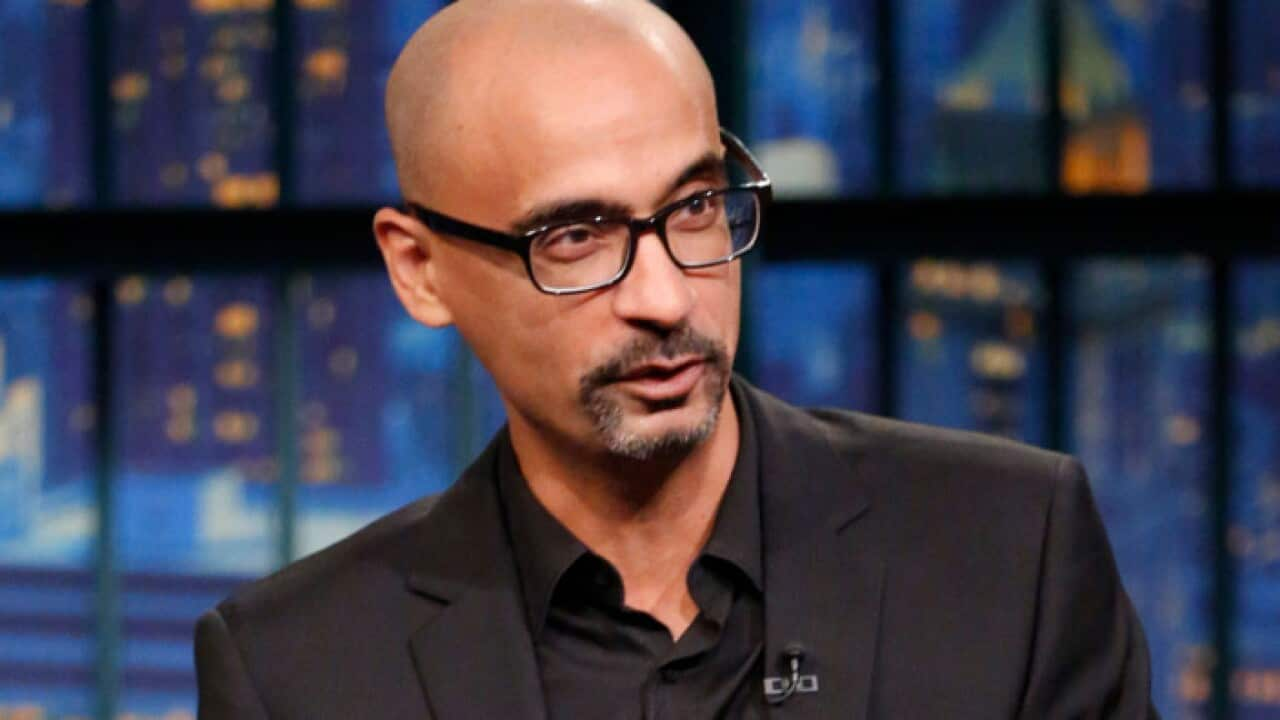

If Junot Diaz was hoping the accusations of sexual misconduct and misogyny that have dogged him in recent weeks would die away, he’s wrong.

Writer Tremenda Manguita has come out and talked about the challenges women of colour experience calling out PoC stars, in her blog post “I Tried to Warn You About Junot Diaz”.

She writes about her brief relationship with Diaz, how she felt used and discarded by the author and how the Latino literary community moved quickly to discount her experience and shield him.

Black and brown women function as collateral damage in his journey to recovery, and ask, 'What is it like?' Yes, he does leave his women behind in the darkness, emerging clean and free, but the hidden costs of this cleansing are borne by women of colour.

“I wrote on my own blog about the painful experience I had with him when I was in my 20s. He reacted badly to that post, calling me a 'bitch', denying my account, and badmouthing me to many people in NY publishing. The Latino power establishment was quick to slap me down. Who did I think I was? How dare I say anything bad about saintly Diaz, our Latino literary hero! Clearly I was just trying to drum up press for myself, right?”, she writes.

Shreerekha, a south Indian feminist, has also recounted her relationship with Diaz in an online essay “In the wake of his damage” as a story of a man who used women as a stepping stone on his own journey of redemption: “Black and brown women function as collateral damage in his journey to recovery, and ask, 'What is it like?' Yes, he does leave his women behind in the darkness, emerging clean and free, but the hidden costs of this cleansing are borne by women of colour.”

As a young reader I’d always smart at the way literary men treated their wives/girlfriends/mistresses. Ted Hughes and his two suicidal wives, Camus and his line of affairs that drove his wife mad, Sartre with his harem of barely legal students disturbingly sourced via his feminist partner Simone de Beauvoir, V.S Naipul and his physical violence against his wife.

Now we have Junot Diaz following in the great historical tradition of Celebrated Male Artists Who Are Total Arseholes to Women.

The difference is today women are not taking it anymore.

The disparities women experience in art, academia and journalism were once only railed about by women’s studies departments or feminists. They were easy to swat away, a sideshow distraction, while men continued taking the awards and accolades they saw as their due.

The disparities women experience in art, academia and journalism were once only railed about by women’s studies departments or feminists. They were easy to swat away, a sideshow distraction, while men continued taking the awards and accolades they saw as their due.

These conversations are now centre stage and part of a mainstream conversation fuelled by #MeToo and #TimesUp interrogating power and abuses of power by individuals, in our relationships and how it shapes all our institutions and culture.

Hell, even the Nobel Prize board is implicated, with the literary prize suspended this year in the wake of harassment accusations linked to the jury which administers the award.

The internet has opened up and amplified unheard voices, as women take to the blogosphere to speak about their experiences with Diaz in the wake of his controversial exit from the Sydney Writers’ Festival last month, after writer Zenzi Clemmons accused Diaz of sexual harassment.

Diaz was in Sydney to promote his children’s book Islandborn. He had just published a heartbreaking piece in the New Yorker about being assaulted as a child and how it has shaped his experiences with women, including his semi-autobiographical book This is How You Lose Her, based on a protagonist who deals (or not deals) with his trauma by cheating on his girlfriend in a series of brutally callous encounters.

I remember reading an extract of the book when it first came out with a vague unease. I identified with the women and felt their erasure of their voices, mediated through the male protagonist as a kind of violence. Here they were sidelined and flattened again not just in real life but in art. I wondered what were their experiences, their heartaches, their traumas, their stories? So much of this Diaz affair is symptomatic of the marginalisation women, and especially women of colour, experience not only in love and in patriarchal societies, but in art – the erasure, the laborious backdrop to someone else’s star, bearing all the social cost and pain and none of the fruit.

Even while being highly self-aware of racial and feminist politics, like so many so-called progressive men, Diaz steamrolls ahead bullying, harassing, and demeaning the revolving door of women in his life. Women who function as convenient punching bags to his star – students, fans and those with less power.

Even while being highly self-aware of racial and feminist politics, like so many so-called progressive men, Diaz steamrolls ahead bullying, harassing, and demeaning the revolving door of women in his life. Women who function as convenient punching bags to his star – students, fans and those with less power.

When Manguita, now a powerful author in her own right, offers Diaz a compliment on his Pulitzer Prize years later, he offers a backward compliment telling her “lots of girls in my classes like your books.”

“Girls like my books. Girls in his classes like my books. Not the guys, of course, because he’d never, you know, tell anyone about my books. Just girls read me,” Manguita writes in her blog post. “But the world – the WORLD – likes his books.

“I was pissed that the New York literary establishment coddled this vindictive, woman-hating machista writer, allowed him a high-profile, sanctimonious podium from which to present himself to the world as some sort of grand liberal with a bleeding heart for injustice, a profound voice we should all listen to.”

Male Genius, who could opine on injustice and humanity and art but paradoxically fail to embody those very virtues in their treatment of women.

Whenever I expressed misgivings at the Male Artist and the way men have centred themselves at the expense of women in these relationships of power disparity, it made me the "uncool" girl. I was somehow devaluing freedom and creativity. "It’s about the art not the artist", "but they are a genius!" "This is how artists roll – vive la liberte!"

There was never a consideration at how this libertine landscape impacted women around these Geniuses, who had less power. The women who were the muses, groupies, note-takers, child bearers, who did the domestic work and if they were artists, seemed to always play second fiddle and supportive cast member to Male Genius.

No more.