John Young Zerunge believes that what goes around, comes around. The acclaimed Hong Kong-born Australian artist recently spent time in Young, the New South Wales township that played host to the Burrangong goldfields — where Chinese miners endured ten months of threats, burglaries and violence between 1860 and 1861. Although over 150 years have passed, he says that some things haven’t changed.

“The Lambing Flat Riots are not part of mainstream history,” he tells SBS. “But they’re a political flashpoint and a catalyst for the restrictions on Chinese immigration that led to the White Australia Policy later on. The hate speech I came across in newspapers from the 1860s is so relevant to this Trumpian moment. Back then, the alpha right also considered hate speech to be free speech. I thought that was really interesting.”

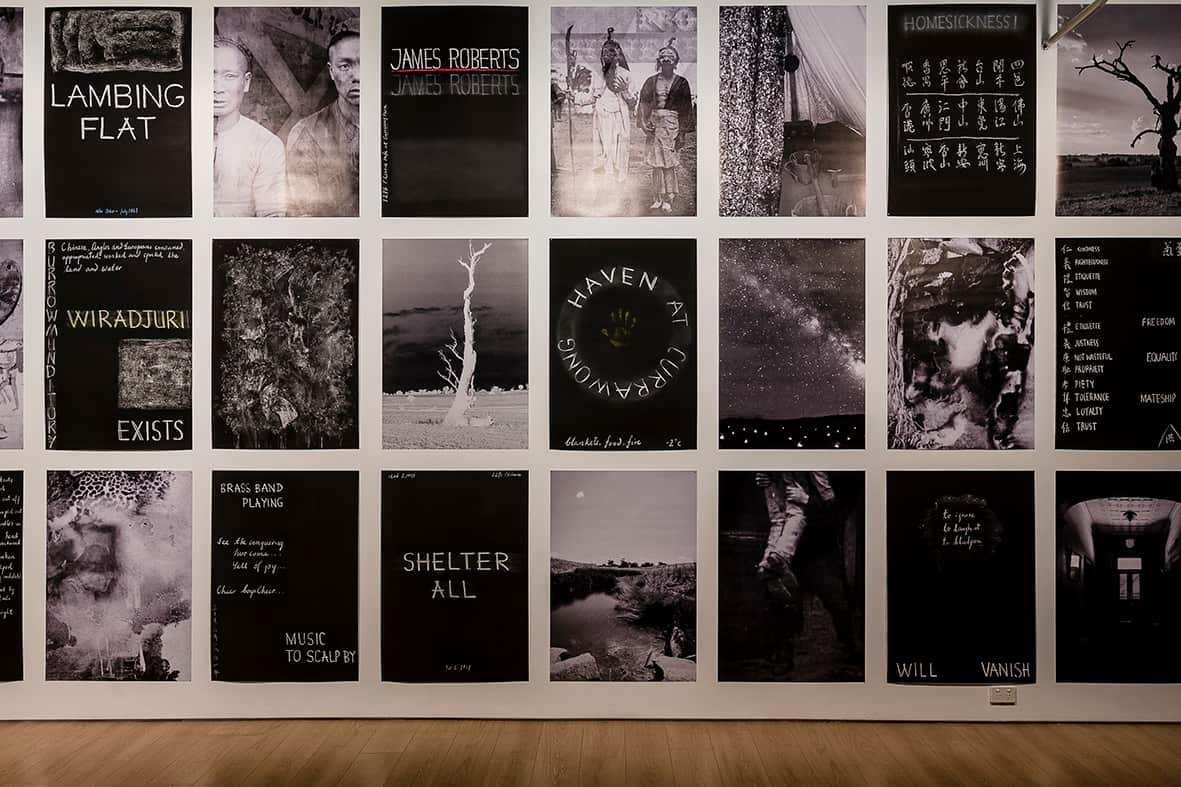

Young Zerunge’s discoveries are the basis for The Burrangong Affray, an ambitious exhibition at Sydney’s 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. The show, which was curated by Mikala Tai and Micheal Do and also features mixed-media installations and paintings by rising Chinese-Australian artist Jason Phu, revisits this underexplored part of Australia’s becoming. But while it draws attention to these dark narratives it uses playfulness and empathy to divest them of some of their heaviness. It also lends the racist caricatures associated with the Chinese-Australian experience in Australia a sense of complexity and depth.

On the first floor of 4A, Phu re-imagines “Roll Up, Roll Up, No Chinese”, the slogan that adorned the cloth banners British miners waved during “roll-ups” — weekly gatherings organised to protest the Chinese presence in regional Australia. (Phu’s version riffs on Chinese contributions to Australian society). And on the far wall, Young Zerunge nods to pigtail-pulling that was rife on the goldfields via The Field, a hypnotic video work that sees a man’s hand tug a braid belonging to a freckled, Anglo-Australian girl. Young Zerunge says that he wanted to foreground the violence suffered by Chinese miners — while drawing attention to the ways in which we can all be complicit in abuses of power.

“The Field references the pigtail pulling, the altercations between the miners and the Chinese but the whole thing plays out like a dream sequence,” he explains. “I reversed all the signifiers and in doing so, tried to universalise this act of violence. It’s about taking the event out of the particular and into the general.”

In Australia, anti-Chinese sentiment started life on the goldfields. You can hear its echoes today from debates about housing affordability and selective schooling to the return of Pauline Hanson. But Young Zerunge believes its equally important to focus on the affinities that have always existed between Australians of different backgrounds despite the odds. The exhibition also features a series of images of the land near Currawong Farm, where a squatter called James Roberts offered food and shelter to the nearly 1500 Chinese miners who were fleeing for safety. In a world that’s increasingly defined by polarities, it’s an invitation towards optimism and hope.

“For me, it’s important to concentrate on a history of benevolence amid all these traumatic events,” he says. “In the show, there’s a lot of focus on Currawong Farm where 1500 Chinese were housed by James Roberts after being beaten up and chased out of the goldfields. Roberts’ descendants still live there and were so generous to us."

Mikala Tai, the director of 4A, says that The Burrangong Affray has been years in the making. She hopes that the exhibition sheds light on the history of racist rhetoric in Australia as well as the stories of inclusiveness that are easy to forget.

“Our past is our greatest teacher and this cultural moment illustrates Australia's conflicting tendencies to both welcome and to restrict strangers,” she says. “The exhibition traces how protectionism can cause long-term cultural division while welcoming and sheltering can build shared communities. In some ways, this story is a warning to us all.”

The Burrangong Affray shows at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art until August 12.