A career retrospective of Australian film pioneer Charles Chauvel in the idyllic country setting of Dungog will be a homecoming of sorts for a director whose underlying themes reflected the man's deepest respect for rural pioneering, Australians at war and Indigenous stories.

For Graham Shirley, Senior Curator (Film) at the National Film and Sound Archive, Chauvel represents qualities that define Australian filmmaking. “Chauvel made films that were personal, epic, distinctively Australian and vividly engaging,” says Shirley, who will attend the Dungog Film Festival for a series of retrospective screenings of the director's work. “Chauvel was essentially a showman, but he was also consciously an artist who wanted to 'paint' Australia on screen. And he did so often by filming on remote and arduous locations that brought that extra something to his films.”

Like a great many craftsmen across all manner of Australian industries, Chauvel began his film career as an apprentice (“A general roustabout,” in Shirley's words) on silent action films being directed by one of Australian film's unsung innovators, Snowy Baker. He followed Baker to Hollywood, where he honed his craft before returning to Australia in the 1910s. The film community of the time was led by an old-guard of directors such as Raymond Longford, Franklyn Barrett and Beaumont Smith, and it was struggling in the face of American imports.

“Chauvel was of a new, younger generation determined to make Australian films that were so uniquely Australian, they would appeal to audiences at home and abroad,” Shirley recounts. But this was easier said than done. “To screen his two silent features, Moth of Moonbi (1926) and Greenhide (1926), Chauvel had to literally pay exhibitors to discard the US films they were contracted to run in their cinemas.”

His early films (Moth of Moonbi, Greenhide and Heritage) were broad representations of the pioneering lifestyle through which Chauvel was able to hone his aesthetic . “The portraits of rural people reached their most sophisticated form in Sons of Matthew (1949),” observes Shirley, who notes that Australia's strong tradition in newsreel excellence was a factor in Chauvel's visual style. “He took until 1940 and Forty Thousand Horsemen to hit his stride as an accomplished filmmaker. His films about war – Forty Thousand Horsemen, The Rats of Tobruk and his World War II shorts for the Department of Information – were all based on a strong documentary reality.”

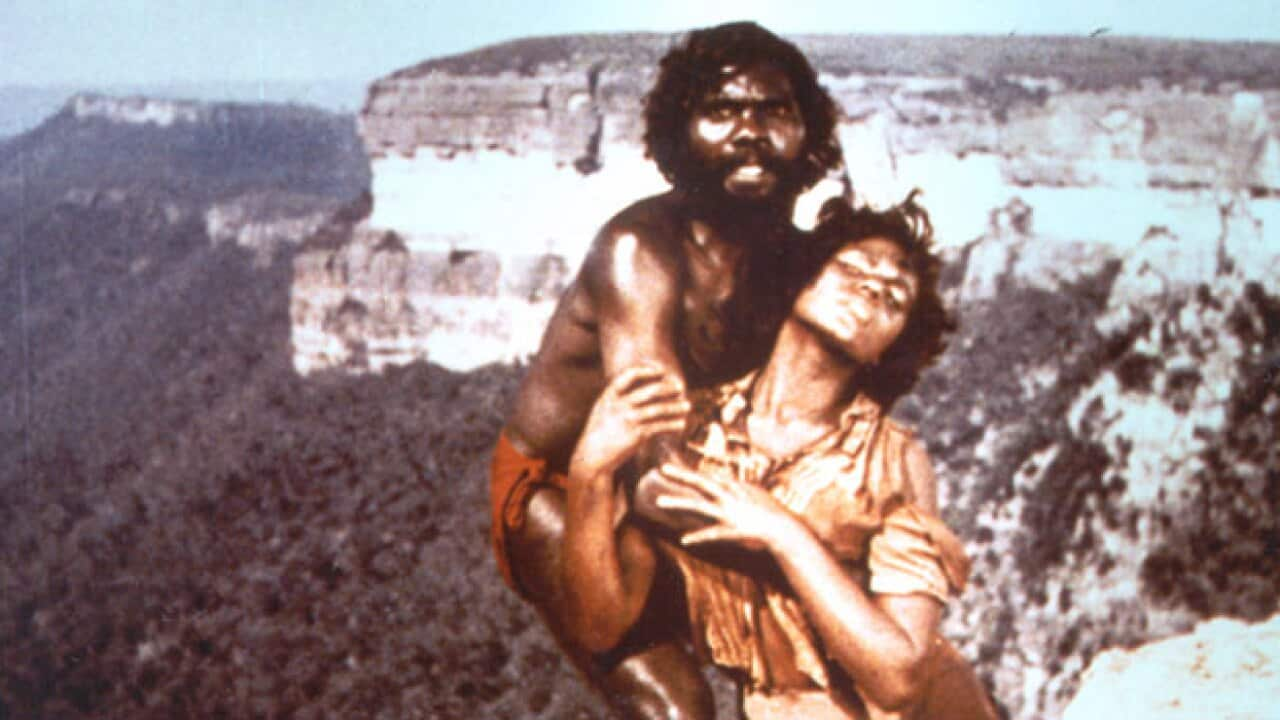

In addition to The Rats of Tobruk (1944, left), the Dungog retrospective will screen two of Chauvel's most accomplished works: In The Wake of The Bounty (1933) and his crowning achievement, Jedda (1955). All three films define clearly Chauvel's skill and growth as a director, and display the narrative and technical developments of the blossoming Australian industry. For example, In The Wake of The Bounty was a flawless mix of drama and documentary (the film includes historically significant footage of the mutineers' descendants on Pitcairn Island); The Rats of Tobruk production unit authentically recreated the deserts of North Africa on the sand dunes of Cronulla in Sydney's south, and blended actors Peter Finch, Chips Rafferty and Grant Taylor seamlessly into action captured by frontline cameramen during the actual conflict.

Graham Shirley notes that despite Chauvel's skill at capturing the psychology of men in conflict (be it Errol Flynn's turncoat Fletcher Christian in... The Bounty (left) or The Rats of Tobruk's traditionally 'Aussie' disregard for authority figures ), Chauvel himself was a humanist with no specific political leaning, onscreen. “Chauvel appears usually to have been apolitical in the public sense, although his family background was that of well-to-do farming and a military tradition,” concludes Shirley, who reminds us that this is in spite of an uncle being World War I military figure General Sir Harry Chauvel. Even Chauvel's wartime shorts were not so much political as propaganda. “(They were) educational and message films – emphasising the importance of contributing to the war effort in While There is Still Time, encouraging the greater production of coal in Power to Win, using ship-building to stress the great potential of national achievement in A Mountain Goes to Sea, and emphasising the importance of heavy industry in Soldiers Without Uniform.” But Shirley concedes that when Charles Chauvel finally expressed a political position, the resulting film was a masterpiece. “The closest that Chauvel came [was] through the portrayal of a 'stolen generations' figure in Jedda.” “A comparatively crude portrayal of Indigenous people in Heritage and Uncivilised gave way to totally believable Indigenous people in Jedda. (The film) mingled the documentary imperative with Chauvel's by now strong skills as a dramatist”.

But Shirley concedes that when Charles Chauvel finally expressed a political position, the resulting film was a masterpiece. “The closest that Chauvel came [was] through the portrayal of a 'stolen generations' figure in Jedda.” “A comparatively crude portrayal of Indigenous people in Heritage and Uncivilised gave way to totally believable Indigenous people in Jedda. (The film) mingled the documentary imperative with Chauvel's by now strong skills as a dramatist”.

Source: SBS Movies

Charles Chauvel fought to maintain the highest degree of dignity and authenticity in his portrayal of the orphaned Aboriginal woman (played by Ngarla Kunoth, who became an overnight sensation), raised by white settlers only to be lured by Marbuck (Robert Tudawali) back to her tribal people. “There were investors as well as politicians, including Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who thought Chauvel mad for wanting Jedda to feature Indigenous people centre-screen, “ recalls Shirley. “(But) Jedda was based on detailed and considerable research via the journeys that Charles and his wife and production partner Elsa Chauvel made, and from the government files they were given access to.” Graham Shirley recognises it as one of the most important cultural treasures in the nation's film history. “Over the years, Jedda has continued to be an iconic film for Indigenous people as well as white Australians”.

The film's success both at home and abroad, at a time when the industry was struggling (Shirley points out that “it was one of the very few entirely Australian features made in Australia during the 1950s”), did not go unnoticed by international producers. “Chauvel's skills as a showman led to an offer from the BBC for himself and Elsa to make and appear in the Walkabout documentary series,” says Shirley, who bemoans the tragic, early passing of the 62 year-old filmmaker. “Chauvel was still planning further feature films when he died in 1959.”

“Charles Chauvel became far better known nationally and internationally as an Australian filmmaker (than Hall),” says Shirley, drawing comparisons with fellow cinema pioneer Ken G. Hall, who was far more prolific, having produced 17 features in 14 years. But Chauvel, who directed 10 films between 1926 and 1955, changed and grew with a nation that was developing at a rapid rate.

Share