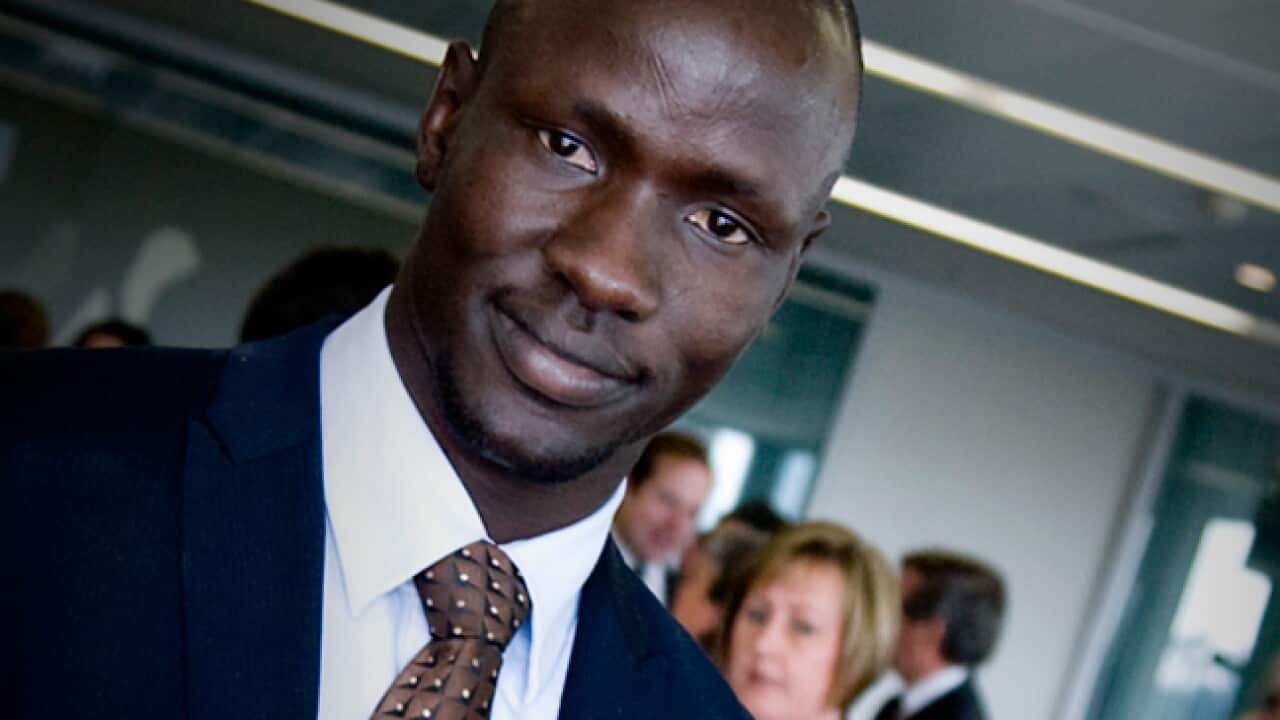

“A child with a gun is somehow not a child any more – they're a solider, a killer” – former child soldier Deng Adut

Deng Adut's time as a child soldier taught him a lot of things: how to plant a landmine, how to operate an AK-47 gun, how to conduct a daylight raid on government targets, who the bad guys were and how to keep quiet to avoid being caned. Unfortunately, he missed out on a host of essential things that most Australian children would take for granted: an education, proper shoes (his were made out of old car tyres and nails) and basic knowledge of personal hygiene. Schooling was a luxury Deng didn't dare dream about.

“We didn't even know how to clean ourselves, to brush our teeth,” he remembers. “In the army, there was no formal [educational] training. Our training was in the use of the gun, on the parts of the gun.”

Incredibly, Deng says he wore the same pair of shorts from 1990 to 1992, all day and night. Every now and then he took them off for few hours to kill the lice by scrubbing them in hot water and burying them in the sand.

“Now I have five pairs of jeans,” he says with a smile. “Sometimes I wonder why I'm buying all this stuff when I was living on one pair of pants for years.”

A refugee from the southern Sudanese conflict in the 1980s, Deng was inducted as a child soldier into the Sudanese People Liberation Army (SPLA) at the age of seven.

“We were not taken [into the army] against our will because we did not even have a will from the beginning,” he tells me.

The children were told how the government in Khartoum (Sudan's capital city, in the north) detonated bombs and killed civilian children.

“They preach these stories…and for kids you take those things seriously…so your main aim becomes to grow up, go to Khartoum and fight them in war, and to kill as many people as you can…That was our aim as children.”

Soldiers in the SPLA were subject to regular torture rituals as military discipline for failing to obey orders. “Some of them are horrible”, Deng recounts. “As a kid, I went through about 40 of them.”

Canning was standard punishment, but there were more severe forms for troublemakers.

“An extreme one is…basically they dug a hole and put you in it [standing up]…they get a barrel, cut the top off and put it on top of you. And leave you there for hours, in the sun. It's extremely hot in there…your head feels like it's going to pop,” Deng explains, “and when you get out you can't even stand up”.

The last resort for a disobedient soldier? Facing the firing squad, which Deng witnessed several times.

With war came injuries and near death experiences.

“I was running away and got shot in the back. It went through my groin but I kept running because I was scared to death…when you're that scared, you don't even know that you've got shot. So I reached a hiding place and realised I had a bullet in my back. Then I collapsed because of the blood.”

He was taken to a hospital in Kenya, where the staff knew very well he was a child solider but were apparently unable and perhaps unwilling to act.

Besides, the reality and desperation of the situation was clear to everyone. “They knew we were doing our best to liberate our country…Besides, if they don't support that idea [of child soldiers], where is the SPLA going to get their soldiers from?”