I was six months old when I came to Australia.

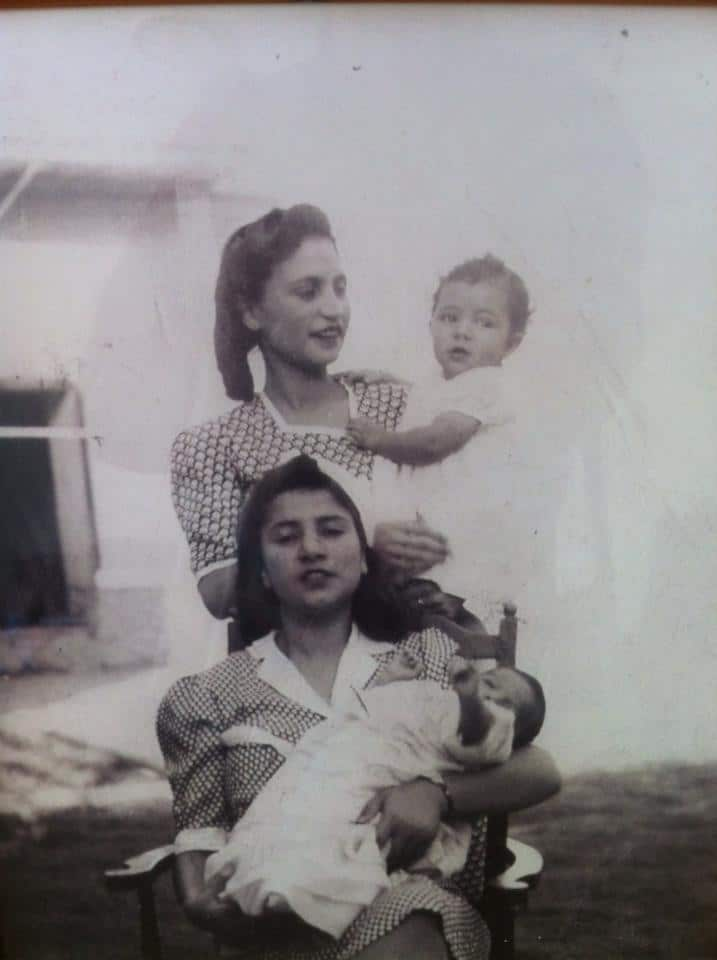

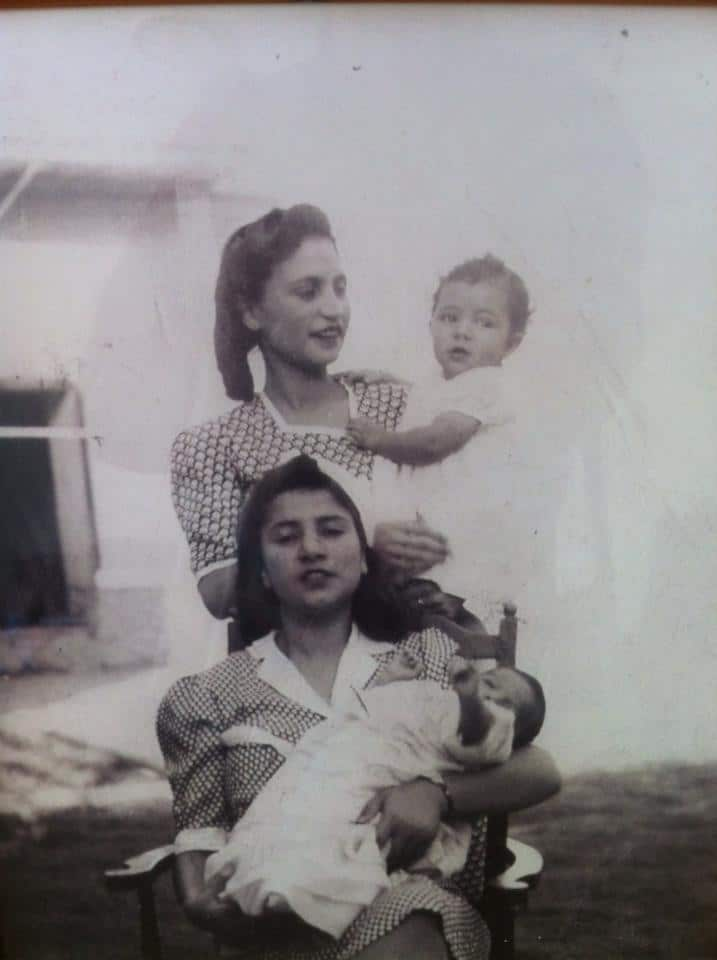

I grew up with stories of inspirational women from my place of birth, Afghanistan. Women like my grandmothers, Khadija Ali Ahmadi, who paved the way for nurses after becoming one of the country’s first midwives and Zahra Kohistani, who despite living in the outskirts of the country was awarded Mother of the Year for raising eight educated children.

That was back in the 1920’s. Today Afghan women’s rights are at crossroads, a cocktail mixed with fear and hope. Fear of their hard-won progresses reversing as troops withdraw and hope for a new beginning. A century and precisely two generations later, I found that ray of hope after speaking with Director of the Afghan Women’s Educational Center Zulaikha Rafiq and Colonel of the Afghan Police Najibullah Samsour at the Amnesty International/Oxfam event.

"The situation on the ground has changed dramatically with women entering public life as professionals in various fields," Zalaikha said.

"There are more than thirty channels on television, featuring women as journalists and singers," Colonel Samsour told me.

Right now is a crucial turning point for women in Afghanistan as they get ready for a new president. They have come so far, but they need the support of the international community. I recall going to an event a few years ago to discuss the implications of foreign troops withdrawing and meeting the wife of a soldier who died in Afghanistan. It was about the time that there was an acid attack on schoolgirls when this woman expressed her views while commemorating her beloved husband.

I recall going to an event a few years ago to discuss the implications of foreign troops withdrawing and meeting the wife of a soldier who died in Afghanistan. It was about the time that there was an acid attack on schoolgirls when this woman expressed her views while commemorating her beloved husband.

"If we were to abandon these girls now it would be a disservice to those brave men who have sacrificed their lives protecting them," she said.

"They are grateful, they are hopeful that the world will stand with them and not turn their backs," Zulaikha said about the women’s attitudes towards foreign troops.

The progress of Afghan women’s rights since the reign of the Taliban is undeniable. Infant mortality rates have reduced, there is access to education and women are claiming their place in the public sphere.

Today Afghan women are sadly symbolic of a piece of blue cloth, declared as "women living in one of the worst countries on earth". We often hear of forced marriages, honor killings and rape as every day atrocities, unfortunate realities that have been magnified on television screens and papers since the West’s mission to "liberate" Afghan women in the 2001 US-led intervention. A mission that began with the US funding of the Mujahedeen where Afghanistan became a proxy during Cold war rivalries and extremism flooded the country, a country that had been quite moderate until then.

A mission that began with the US funding of the Mujahedeen where Afghanistan became a proxy during Cold war rivalries and extremism flooded the country, a country that had been quite moderate until then.

It was a breakthrough moment for Afghan women when they took the streets to vote on April 5 to be a part of shaping their country’s future. But the complexities that Afghanistan poses internally and regionally makes this a crucial moment for advancing Afghan women’s rights.

"We cannot forget Afghanistan has a society entrenched in tribal customs ... ten years is not enough," Zulaikha said.

After a decade long involvement with the country, Australia has the ability to make Afghan women’s rights a priority through their role in the United Nations Security Council and allocation of aid money to grassroots organisations rather than government bodies.

Women can no longer be bargaining chips in negotiations; the time to act and implement legal mechanisms that uphold their human rights is now. To only be known as the "worst place in the world to be a woman" defies our historic foundations, everything that women like my grandmothers worked to achieve then and all that we have lost along the way.

Amnesty International has worked for more than 20 years to protect and advance Afghan women’s rights.

Share