Battered and bruised, 26-year-old Pia Jain* barricaded herself behind the bedroom door of her home and dialled the number for the police. Moments before she had been pinned to the floor by her husband’s foot, struggling to breathe and, for what wasn’t the first time, thinking he might be about to kill her.

This was almost four months into the marriage that was arranged by Ms Jain's parents. The abuse had started on her wedding night.

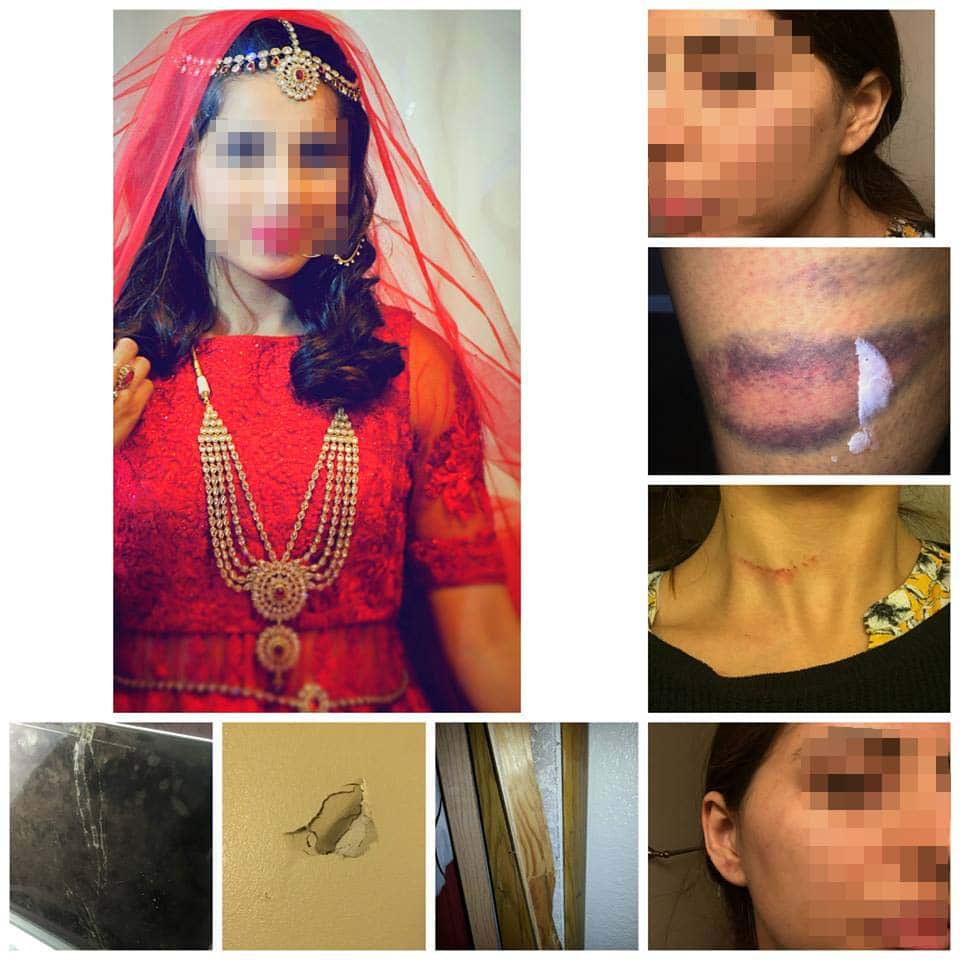

"He would pull my hair and punch me so badly my contacts would fall out"

In Ms Jain's own words, she was "crazy about getting married" to the man her parents had picked to be her husband.

"[I was so] smothered by his charm, kindness and politeness. And not just me, my whole family was," she said, recalling the six months leading up to their wedding in which they mostly spoke over the phone.

"I was head over heels [in love] with him."

Like her, he was highly educated and came from an affluent Hindu family who had migrated from India -- his family to the United States, Ms Jain's to Australia. Both had successful careers and financial independence. He was a financial adviser while Ms Jain was running her own fashion label.

There was no dowry exchanged. The soon-to-be wedded couple had no need for it -- they were equals when it came to their socio-economic status. They seemed like a perfect match.

"I got married to what I thought was a really amazing, sensitive, really intelligent man," Ms Jain told SBS Hindi.

She said she could have never predicted his personality changing within hours of their wedding.

"My wedding night was miserable," she said. She remarked to her new husband that she was missing her brother when he turned on her. "How dare I say I love someone else but my husband," she recalls him saying.

Their honeymoon was similarly unpleasant and by the time they were living together in his hometown, she said it was "the most miserable time of my life".

"Before he started hitting me he used to just be very rude," she told SBS Hindi.

"He started talking like he owned me, like he could tell me what to do, and if I miss[ed] one thing and didn’t listen to him he would get so angry and mad that he started throwing things around."

Within no time, she too became one of those things being thrown violently around by her six-foot-two husband.

"[I had] bruises on my face because he kept smashing it against the bathroom shelf. [He would] choke my neck to take my phone away and lock me in a room so I [couldn't] call anyone for help," Ms Jain said.

"He would pull my hair and punch me so badly my contacts would fall out."

Despite this, Ms Jain didn't want to shame her family with a divorce. She was well-educated, well-travelled and had grown up in Australia but Hinduism was the centrepiece of her life.

"As a cultured woman, I couldn’t let my marriage break," she said. "I always wanted to be with one man for the rest of my life".

The shame and stigma of a divorced daughter

This is a common dilemma for many Indian women even if they are second- or third- generation Australians, according to Dr. Manjula O'Connor, a Melbourne psychiatrist and the Director of the Australasian Centre for Human Rights and Health.

"The continuity of Indian culture, in Indian diasporas or Indian migrant communities in Australia and everywhere in the world, is very, very strong. They strive to maintain the tradition, language and the family system," she told SBS Hindi.

"Young women from Indian-origin backgrounds often get married within their community -- so there is a lot of pressure on them to maintain cultural continuity and family tradition even if the women are second or third generation.

"An unsuccessful marriage, or a single daughter, or a divorced daughter, is a shame and stigma for most Indian-background families."

While Dr O'Connor stressed that domestic violence happens in every community and country, she previously told SBS News that "cultures where there are male patriarchal attitudes tend to be more permissive of domestic violence".

"The patriarchal system allows the man to make all the decisions. He is supposed to be the main breadwinner; he is supposed to be the person who should look in charge not only within his home by his wife, his children but also by society," Dr O'Connor told SBS Hindi.

The wider Australian community is not exempt from these patriarchal attitudes that domestic violence experts suggest drive violence against women. According to a 2015 research paper published by national domestic violence prevention organisation Our Watch, more than a quarter of Australians think men make better political leaders, and that one in five think men should take control in relationships and be the head of the household.

The report also added that in the 2014 Global Gender Gap Index, Australia was ranked 24 out of the 142 countries. "We are currently below similar countries such as New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America, and also behind developing countries such as the Philippines, Nicaragua and Burundi," the report said.

"An unsuccessful marriage, or a single daughter, or a divorced daughter is a shame and stigma for most Indian-background families."

In February 2017, the general manager of the family violence helpline 1800RESPECT, Gabrielle Denning-Cotter, told SBS that callers of Indian background were the second highest number after Australian-born women.

Brisbane social worker and adviser to Sikh Helpline Australia, Jatinder Kaur told ABC News that while there are no Australian statistics available to help ascertain the prevalence of family violence in Hindu and Sikh communities, she believes this apparent increase in Indian callers may be due to a "huge wave of migration" over the past decade.

Like Dr O'Connor, Ms Kaur believed that Indian culture and its emphasis on the importance of marriage encouraged women to make it and their husband the priority, rather than their own safety.

"Our community come from India, where patriarchy and women's rights are not equal. It is an accepted cultural norm in their country of origin. This is a generational shift which will take time," Ms Kaur said.

"Part of the challenge we face in our communities is a push to preserve the marriage and the sanctity of the marriage."

According to a survey of community attitudes around domestic violence conducted by VicHealth in 2013, "respondents [born in countries where the main language wasn't English] have a relatively high level of awareness of violence, but a poor understanding of its gendered patterns and particular dynamics."

While a relatively small proportion of this group were prepared to justify violence, those who did, agreed that "domestic violence is a private matter to be handled in the family" and were twice as likely as all of those surveyed to believe that "it is a woman’s duty to stay in a violent relationship to keep the family together".

'If your partner hits you once. Please leave. Don't stay. Because it will happen again.... You deserve to be loved and treated with respect.'

At the height of the violence Ms Jain was experiencing from her husband, she called friends and family for help. What could she do to make him stop hitting her?

They all gave the same advice: be patient and don't antagonise him. Her grandmother especially voiced these sentiments: don't "add fuel to the fire"; "stay quiet"; and don't react when his temper flares. But Ms Jain very quickly discovered this approach had the opposite effect on him. Her silence made him even more furious.

In a 2016 opinion piece published by SBS Punjabi, Dr Manjula O'Connor quoted sociologist Martin Rew who argued that "mothers and wives are inextricably connected with maintaining patriarchy, male honour and prestige. She is rewarded with special privileges if she stays complicit – public respect, awards, money, and prestige all come her way."

After both Ms Jain's family and her husband's family realised her staying quiet was enraging him more, they tried to make him understand that "hitting his wife was wrong".

When he became violent, she would call her in-laws for help, but "as soon as his dad comes over" he would start to cry. Then she would watch as he was consoled.

"[It was] a mind-baffling experience," she said.

"I did not know if I should feel sorry for him or run for my life".

Her mother travelled over from Sydney to support her daughter and even in her presence, he continued to beat and abuse his young wife.

"It was tough for my mum to see her daughter who was a fun-loving woman, full of life, turn into a slave-housewife who cooks, cleans and gets beaten up by her husband," Ms Jain said.

"[I couldn't] even leave the house with Mum without his permission. I wasn’t even allowed to buy bedsheets, crockery, or even hang a picture in the house without his permission. I wasn’t even allowed to wear lipstick, dresses, everything has to be long to cover my butt, no shorts or skirts."

While her husband's violence and abuse continued, so too did his apologies afterwards, with him crying, begging, and promising he wouldn't hurt her again.

Ms Jain twice packed her bags and twice bought a one-way ticket back to Sydney. Both times he talked her out of it and promised he would change.

"He promised me, he promised my mum, he promised his dad, he would not hit me again but it happened again. And it happened again and again."

The months of torment finally came to a head soon after Ms Jain's husband convinced her again to stay, four days after her mother returned to Australia.

'I called the police because I was scared for my life'

Early in the morning, her husband went to kiss her when he saw a pimple near her lip. He accused her of having an affair and stamped his foot down on her chest. Although struggling to breathe, she managed to scramble out from under him and lock herself in another room, where she called the police.

"I was so scared," Ms Jain said, "I called the police because I was scared for my life".

Officers arrived and surveyed their home: the broken laptop and bookshelf, the door pulled off its hinges, the broken windows and the bruises on her chest. They handcuffed him and took him away.

Over the next year and a half, Ms Jain received a criminal protective order and restraining order against her former husband, and when her divorce was eventually finalised, she posted a long message on Facebook declaring: "I am so happy to say I am no longer married".

After thanking her family and friends who supported her through her ordeal, she finished her post with a direct plea to other people trapped in abusive relationships.

"I know how hidden this topic is... If your partner hits you once. Please leave. Don't stay. Because it will happen again. Ask for help. Don't be ashamed. Seek therapy, see a psychologist, recover, meditate, travel and love yourself, respect yourself. You deserve to be loved and treated with respect."

*Names and some locations changed for legal and security reasons

Family and domestic violence support services:

- 1800 Respect national helpline: 1800 737 732

- Women's Crisis Line: 1800 811 811

- Men's Referral Service: 1300 766 491

- Lifeline (24 hour crisis line): 131 114

- Relationships Australia: 1300 364 277

- Sikh Helpline: 0401 401 040

- InTouch Multicultural Centre Against FV: 1800 755 988 (Vic)