Malaria transmitted by mosquitos kills half-a-million people globally every year but at this Brisbane laboratory, they’re turning the tables infecting a human with malaria first.

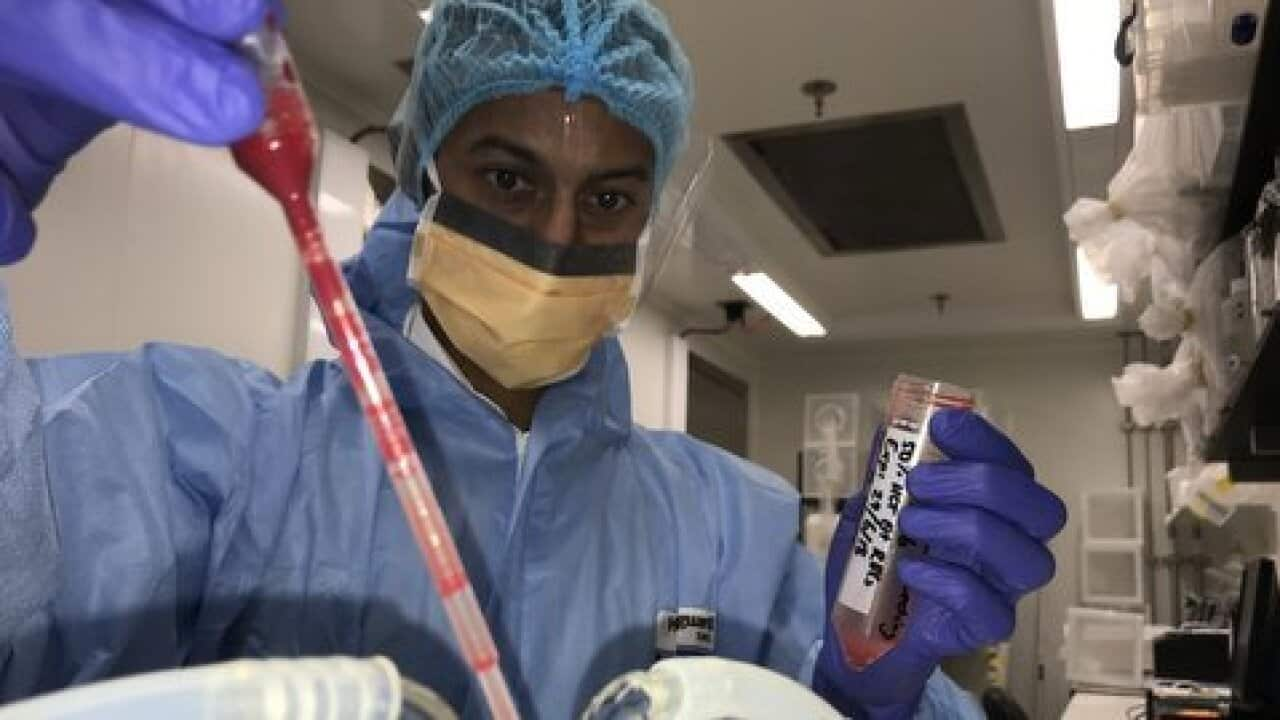

Hundreds of volunteers have been infected in clinical trials to test for human-to-mosquito transmission of the malaria parasite by Doctor Anand Odedra, a clinical researcher at Q-I-M-R Berghofer.

"Lie back and make yourself comfortable, Andrew, as you know today was going to infect you with malaria it’s less than you would get from a mosquito bite. And we just make sure you’re okay, everyone has been okay so far, we’ve done this more than 300 times.

Volunteer Andrew is not worried, he regularly gives blood and says he is doing this for the public good.

"No, it doesn’t make me nervous at all because I know there are two different types of treatment that are very effective."

Doctor Odedra says in a world first, they have been able to achieve human to mosquito infection in a safe clinical environment, but what they’re trying to do now is perfect a reliable technique to test the effectiveness of drugs that stop transmission.

"So we're the world's experts in these kind of trials, we have infected more people with malaria in a controlled environment than anyone else. We're also now working towards, as well as assessing how well drugs work to treat malaria, we're looking into trying to prevent the spread of malaria and testing new drugs and interventions and we’re the first to really successfully do that in this kind of setting."

After two weeks, the volunteers are active malaria hosts ready for human to mosquito transmission.

The adult malaria parasite that causes the sickness is killed with a drug leaving only its male and female offspring to incubate.

The new method sterilises the parasite at the critical time when it becomes sexually active and spreads.

Senior scientist Professor James McCarthy is an infectious disease specialist at Q-I-M-R Berghofer and will lead its delegation to the World Malaria Congress in Melbourne.

"So what we're trying to do is to think outside the box and develop a way to actually interrupt the malaria transmission, normally we're aiming to treat the parasite inside people that’s making them sick, but if we can get rid of the ability of the malaria parasite to transmit to mosquitos, then we can actually block the onward transmission of malaria and therefore basically get rid of it. So this is a completely new way of approaching malaria elimination.'

Currently, the same type of tests can only be done in infection zones.

Australia been a leader in malaria research since the Second World War and has been disease free since the 1960s.

Professor Sir Richard Feachem helped found the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria and chairs the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication.

He says Australia’s role in funding research and the global campaign is recognised internationally.

"Australia punches well above its weight on malaria through both fundamental and applied malaria research and that is happening and it's largely funded by the Australian taxpayer, through the Australian government.

Malaria afflicts more than two-hundred-million people globally, the highest rates are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia and Papua New Guinea.

Huge progress has been made globally fighting the disease with Paraguay last month being declared the latest malaria free country, and Algeria, Argentina and Uzbekistan to follow shortly.

But Sir Richard Feachem says the emergence of drug resistant and monkey strains of malaria in South East Asia could reverse decades of gains and cause millions more deaths.

"What we currently face is the third time in history where the commonly used malaria drugs have met increasing resistance by the parasite and in every occasion this has occurred first in the Mekong countries of South East Asia and then has subsequently jumped to both India and South Asia and to Africa, so we’re very apprehensive about this."