On the morning of 1st February 2021, Myanmar’s democratically elected government was overthrown by the country’s military, and a one-year state of emergency was declared. Telephone networks and the internet were disrupted throughout the country and private and public TV channels banned, with only the state’s military-run TV channel able to broadcast.

For journalist Som Thapa*, it was a case of "not again", as his social media feed started filling up with posts about what may have happened to the ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other senior political figures from the National League for Democracy (NLD).

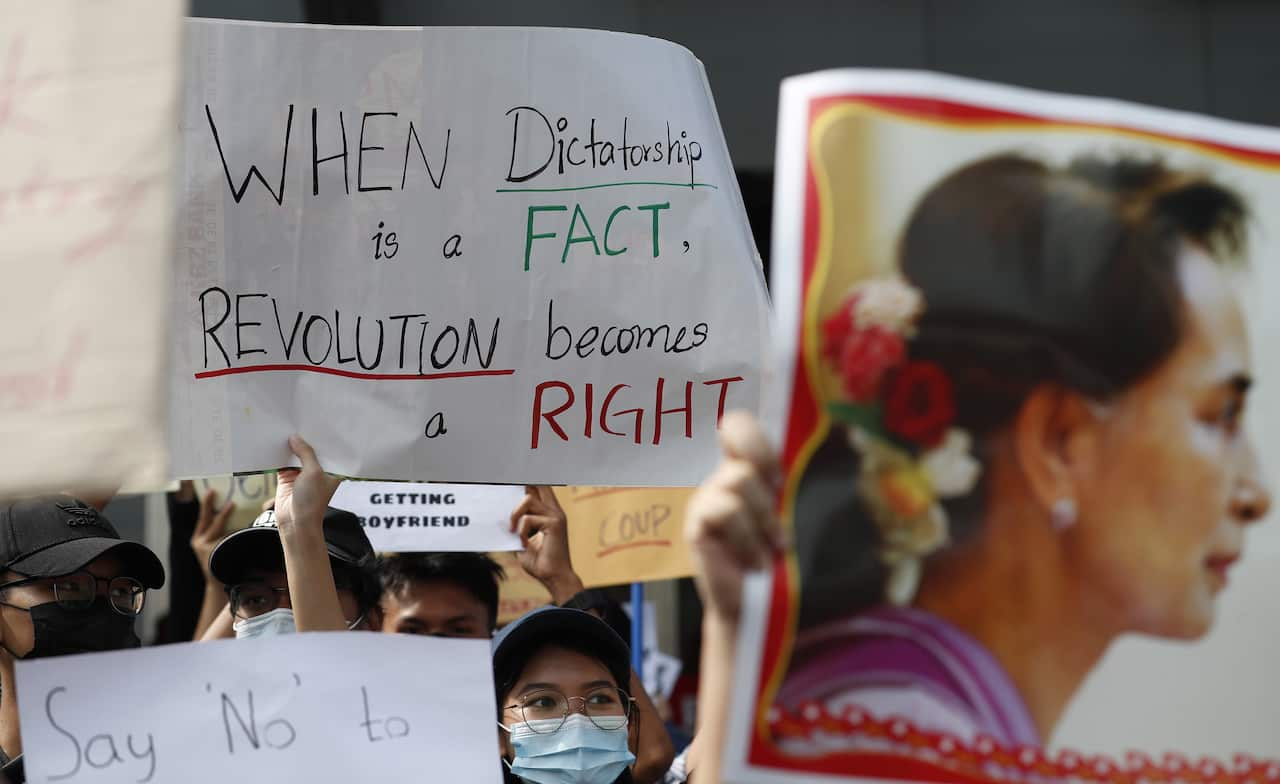

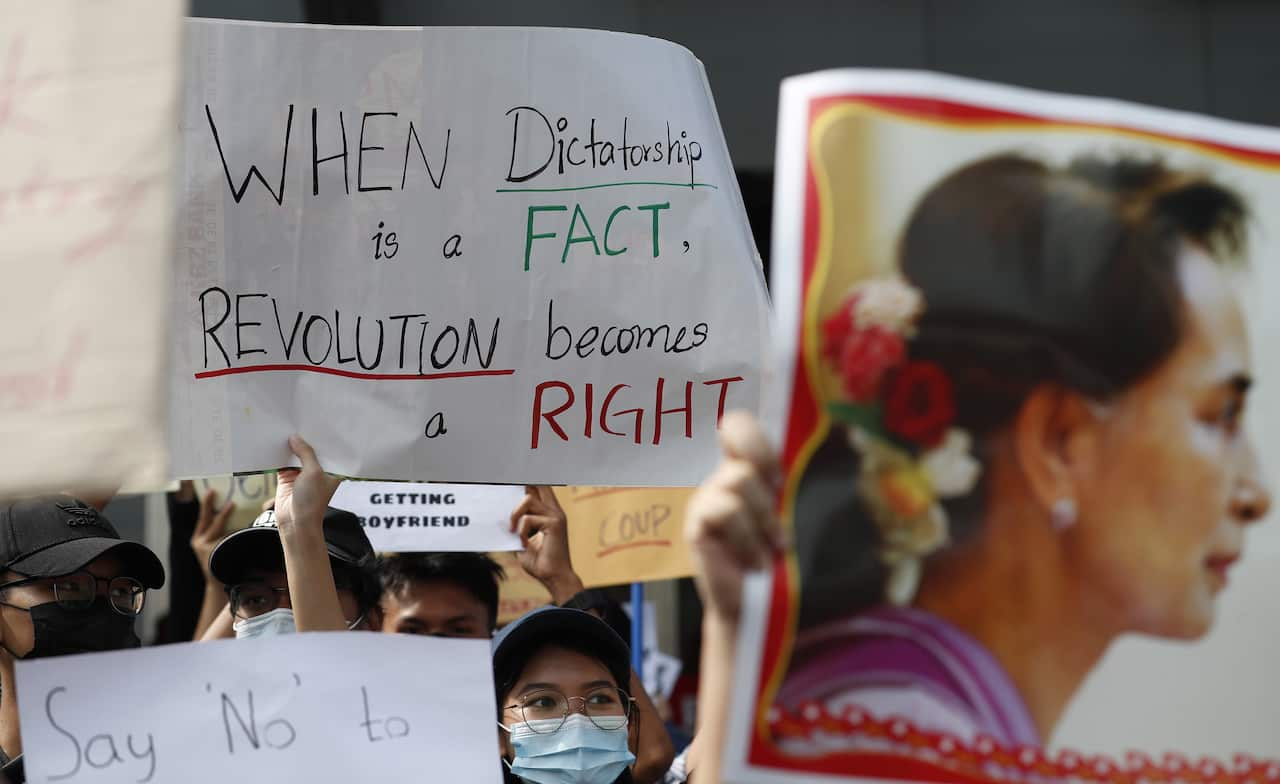

Hundreds gather to protest against Myanmar coup in Melbourne on Saturday 6 February, 2021 Source: SBS/Jin Sun Lane

Déjà vu for a Nepali journalist in Myanmar

On the same day 16 years ago, Som Thapa had experienced another government take over - in Nepal - with soldiers stationed in the newsrooms of various media outlets.

In 2005, the then King of Nepal, Gyanendra, had sacked the democratically elected government led by Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba. Mr Deuba and other politicians were detained under house arrest, communications cut, there was complete censorship over media and a state of emergency declared.

Mr Thapa, who was working as a journalist for a private television company in Nepal, clearly remembers how events unfolded on the day.

"I was on my regular workday and suddenly there was news from the government broadcaster – Radio Nepal or Nepal Television – that the King [Gyanendra] is going to address the nation."

"I talked with the cabinet ministers, but no one was sure what the King’s speech was going to be about," he told SBS Nepali. At the time Nepal was a constitutional monarchy, like Australia. However, it wasn't the first time the King had sacked Prime Minister Deuba and assumed executive control of the country. He had taken the same steps in 2002.

At the time Nepal was a constitutional monarchy, like Australia. However, it wasn't the first time the King had sacked Prime Minister Deuba and assumed executive control of the country. He had taken the same steps in 2002.

An armed Nepalese policeman stands guard in front of a billboard portraying King Gyanendra with a slogan "Beginning of Nepal's new era" in Kathmandu, 3 Feb 05. Source: EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images

"For the ministers to be unaware of the King’s agenda was unusual, it raised many questions," he says.

With his camera crew, he headed to the residence of Madhav Kumar Nepal, then chief of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified-Marxist Leninist) [CPN (UML)], which was also a part of the coalition government.

As the royal coup was being declared, events took an unprecedented turn.

All telephone networks and internet connections were disrupted within minutes, and prominent leaders detained. "As I was interviewing Mr Nepal, the deputy superintendent of Police from the armed forces' unit, came and detained the communist leader."

"As I was interviewing Mr Nepal, the deputy superintendent of Police from the armed forces' unit, came and detained the communist leader."

Nepalese soldiers patrol a street near the Royal Palace in Kathmandu, 01 February 2005, after King Gyanendra dissolved a coalition government. Source: DEVENDRA M SINGH/AFP via Getty Images

"He could not complete his sentences in front of my camera – he was against the coup and was saying it was “unacceptable” and “people will protest against it."

"Back in my office - a major and some soldiers from the Nepalese army had come to our newsroom and went through all the news items and every political news about the royal coup was censored.

"We were only allowed to broadcast the diverse beauty of the country", he adds. Media and newspaper censorship, along with no telephone connection continued for many weeks – followed by protests, and widespread criticisms at home and abroad.

Media and newspaper censorship, along with no telephone connection continued for many weeks – followed by protests, and widespread criticisms at home and abroad.

A group of journalists hold dead mobile phones, whose service has not been restored, in a protest rally against the government plan to muzzle the press. Source: DEVENDRA M SINGH/AFP via Getty Images

The reason the king gave for his action was that the political parties were only focused on power and unable to end the armed insurgency launched by the Maoist rebels against the government. The conflict had claimed the lives of more than 11,000 people by then.

Situation in Myanmar

Fifteen years on, rumours and concerns over a possible military coup had already started in Myanmar prior to 1st of February.

The country’s November 2020 elections were followed by numerous allegations of fraud by the military leaders, with claims such as names of deceased people being on the voters' list.

The National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi had achieved a landslide victory securing at least 397 seats in the 476 seat parliament. This was the second democratic election of the country after its 49 years of military suppression, which ended in 2011. As thousands of protestors swarmed the major cities in Myanmar in the last few days, the army has now restricted outdoor gatherings. However, protestors have continued to take it to the streets in cities like Yangon and Mandalay.

As thousands of protestors swarmed the major cities in Myanmar in the last few days, the army has now restricted outdoor gatherings. However, protestors have continued to take it to the streets in cities like Yangon and Mandalay.

Thousands of people took to the streets for a third day of mass protests against the military coup in Yangon. Source: EPA

Protesters chanting slogans of "we need democracy” and “reject the military” are demanding Aung San Suu Kyi's release from house arrest.

With private and public media broadcasters banned, the safety of journalists has also become a big question.

"Journalists are not feeling safe – some have already started reporting from hiding and some are fleeing to the Thai-Myanmar or Myanmar-India borders for reporting. However, there have not been any reports of journalists being detained or bullied so far", says Som Thapa.

In areas with internet access, social media has been a helpful tool to send and receive the latest information to the rest of the world. Mr Thapa continues to post the latest news about the country through social media when the internet isn't shut down. Since the announcement of the coup on February 1 last week, the Tatmadaw’s Senior General, Min Aung Hlaing made his first national address on Monday, February 8.

Since the announcement of the coup on February 1 last week, the Tatmadaw’s Senior General, Min Aung Hlaing made his first national address on Monday, February 8.

Myanmar senior general Min Aung Hlaing. Source: EPA

Although he said fresh elections will be held and power handed to the winner, no date has been set for the elections.

"We don't know what the future holds for Myanmar. We don't know if there will be free and fair elections in the future, we don't know if supporters of democracy will accept the outcome of such elections."

"But, what we know is that people haven't been able to think that far ahead with what is happening in the country at the moment", says Som Thapa.

In Nepal, however, the country's February 2005 state of emergency was withdrawn by the King in April 2005, and eventually, the monarchy was abolished in 2008. The country is now a democratic republic.

*(name changed for security reasons)