In June 1967, Tarsem Singh Sandhu found himself holding the baton of a ‘volatile’ campaign which initiated from a small town in central England but ended up resonating with Sikhs across the globe.

Beginning of the ‘turban dispute’

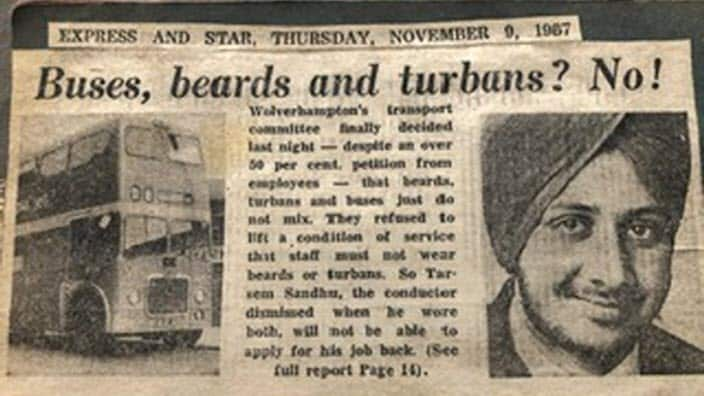

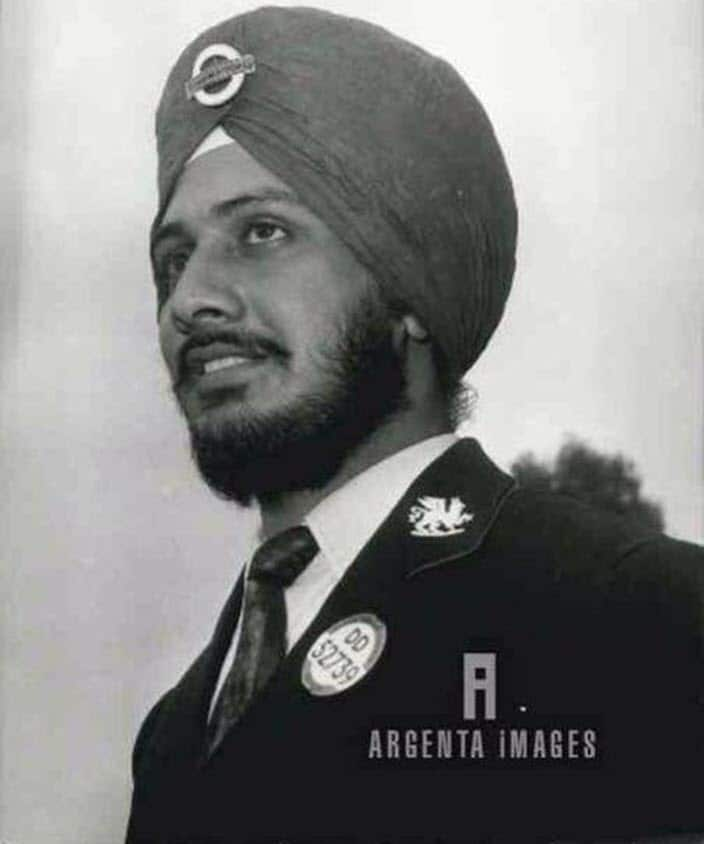

The controversy started when the then 23-year-old Sandhu, a bus driver with Wolverhampton Transport Committee returned to work after sick leave, wearing a turban and a newly-grown beard.

But after one round trip, the young driver was sent home by his supervisor for breaching the existing dress code, thus marking the beginning of a protest that two years later forced the UK authorities to change the law in Mr Sandhu’s favour.

Speaking with SBS Punjabi, Mr Sandhu who is now in his mid-seventies said he was sent home without pay and was asked to return to work without his turban and after shaving off his beard.

“By the time I returned from the first trip, it had created a riot back at work. The inspectors intercepted me and told me that I can’t drive. ‘Turban is not a part of the uniform, they said,’” recollects Mr Sandhu.

“They asked me to go home and return after removing the turban and shaving-off my beard. Something that I vehemently declined,” he added.

Tarsem Singh Sandhu's early days in the UK

Mr Sandhu confirmed that initially when he joined the bus company, he wasn’t a turban-wearing Sikh, explaining that when he arrived in the UK, an impression was formed that "finding work with turbans was hard".

And so he said his uncles pinned him down and he was forced to cut his hair, “against his will.”

But after finding his feet in the country, he re-embraced his religion and wanted that to be reflected in his adherence to traditional Sikh conventions of wearing a turban and maintaining an unshorn beard.

Impact of the ‘turban dispute’

After being sent home, Mr Sandhu launched a campaign which over the course of two years became embroiled in local, national and transnational politics divided between the supporters of city’s Member Parliament Enoch Powell, the Indian Workers’ Associations and the fledgeling Sikh party, the Shiromani Akali Dal.

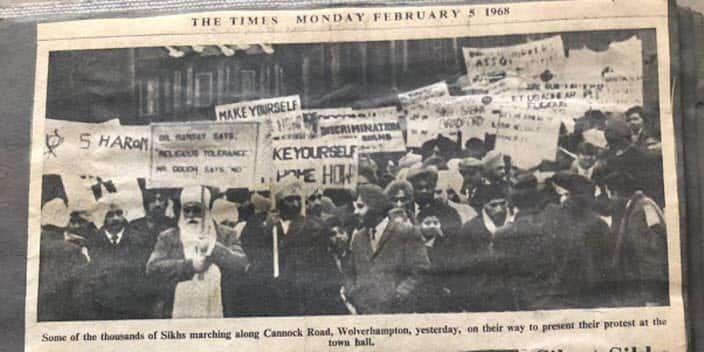

“Initially we didn’t get much support except for a few Sikhs who were keen to join our fight. But gradually, we managed to garner support and over 6,000 people joined our campaign,” said Mr Sandhu.

The then president of the Shiromani Akali Dal, 66-year-old Sohan Singh Jolly, quickly became a front-runner of the campaign.

And the conflict escalated to a point where Mr Jolly, an ex-Kenya police inspector, threatened to burn himself if the transport union refused to allow its Sikh drivers to wear their turbans to work by 30 April 1969.

The news of his ‘suicide campaign’ slowly reached India, where nearly 50,000 men took to roads to demonstrate their solidarity with Mr Jolly and Mr Sandhu.

Meanwhile, the anti-Sikh sentiment also kept intensifying against what was being touted as an “unusual demand” of the Sikhs in the British circles and media.

The conflict reached a crescendo in 1968 when MP Enoch Powell delivered his notorious “Rivers of Blood” speech warning the British population of the “dangers of immigrants gaining power in Britain.”

Mr Powell though was sacked for his fiery speech but his words did leave an impact on the minds of the locals, further strengthening the resolve of the transport union to not change its rule despite the swelling protests.

The end of the ‘turban dispute’:

According to the authors of the ‘historical studies in industrial relations,’ “the country (at that time) was in a grip of widespread industrial action; strikes were a commonplace of everyday life as well as bitter rows over race and immigration.”

As the deadline for Mr Jolly’s suicide threat drew closer, the pressure mounted on the Wolverhampton Transport Committee to review its ban.

Eventually, the committee met with Mr Jolly and other Sikh leaders and after a month in April 1969, it agreed to lift its ban on Sikh bus drivers, thereafter allowing them to wear turbans and beards to work.

While the Sikhs greeted the decision with jubilant cries of ‘Sat Sri Akal’ and ‘Wahe Guru ki Fateh’, The Express and Star editorial argued with a touch of irony that it was “hardly a victory for anyone.”

The media further reported that the committee was “cajoled and forced” to lift the ban, something that was also reflected in their statement which of the union which read that “The committee remains strongly of the view that its original decision was right and its rule both reasonable, and clearly non-discriminatory.”

But the episode nevertheless left an indelible mark on the British Sikh history and has been described as a "key moment" and a "historic shift" in the ‘historical studies in industrial relations.'

Mr Sandhu who emerged as the unlikely ‘hero’ of the long-standing dispute believes that “the hard-fought battle was worth the fight and justice it eventually begot.”

He continues to live with his extended family in Wolverhampton, now reportedly home to one of the largest pockets of the Sikh population living in the UK.

Listen to SBS Punjabi Monday to Friday at 9 pm. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.