For Dr Nouria Salehi, there was a period of time where the smell of garlic and onions would always linger on her hands – an unusual predicament for a nuclear physicist.

“Even now, whenever I smell that, it reminds me of where I came from. It was a difficult time,” she told SBS News.

“But I’m pleased with what I did because it did help a lot of people, so it makes me happy.”

Dr Salehi left a difficult life in Afghanistan behind when she moved to Australia – but she still did not opt for an easy one in Melbourne.

She was a nuclear physicist by day, a restauranteur by night, and a human rights activist around the clock.

The 73-year-old is one of the 755 Australians who received a Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) this Australia Day.

“I’m very grateful, but this award is for all Afghans. I’ve always been aware of vulnerable people, and what I can do for them,” she said.

In 1967, at the age of 22, Dr Salehi left Kabul to complete a doctoral degree on the use of nuclear medicine.

“When I left, Kabul had been poor but stable. When I returned four years later, the politics had changed, and the university was always closed,” she recalled.

She moved to France, where she continued her work on nuclear medicine – and at the age of 37, her brother asked her to join him in Australia.

In 1978, Afghanistan's President Sardar Mohammad Daoud Khan was killed in a coup – an assassination which would set off decades of unrest, culminating in Soviet occupation, and the formation of an Islamic militia which later evolved into the Taliban.

Knowing her beloved country was in crisis, Dr Salehi's flight to Australia was an emotional one.

“Even on the plane I was thinking about what I could do… I knew that I had to continue my professional work, but I was already thinking about how I could help people in Afghanistan,” she said.

“I felt so lucky to be in Australia, that on the day I arrived, I was very ambitious and wanted to contribute.”

Immediately after stepping off the plane, Dr Salehi recalled she asked her brother to stop at the Royal Melbourne Hospital so she could begin working on her research – at the time, there was no budget for a researcher, so she worked as a volunteer for two years, relying on the savings she had earned while working in France.

She eventually secured a position with the hospital, and went on to become a highly respected physicist – her research into the use of radioactive isotopes to detect and treat cancer still benefits many patients today.

But, for Dr Salehi, the plight of Afghan people remained at the forefront of her mind, and for many years she balanced her human rights activism with a demanding medical career.

“I was very naïve when I arrived, I wanted to sponsor people but I was not a citizen, so I couldn’t do that,” she said.

“I cried because I wanted to help them.”

As she walked through the streets of Melbourne, and realised she could not find authentic Afghan food, Dr Salehi decided to open her own Afghan restaurant, as a venture to sponsor Afghan families and to raise money for projects in Afghanistan.

She called the restaurant The Afghan Gallery – and today, it remains a popular spot in Melbourne’s Fitzroy.

“I would start early in the hospital, then cook in the restaurant, peeling the onions and garlic for the qorma (an Afghan meat dish),” she said.

“When my sister arrived, she started to help me. As the community became bigger, it became easier.”

Dr Salehi stopped cooking in 1987 and retired from her role at the hospital in 2017 – but even in retirement, she said she is unable to sit still.

“I always have something in mind, even before I finish one idea, the next idea comes. Now I am thinking about opening a jam factory,” she said.

“When the community needs me, I am there. My door is always open, children come to me, and families come to me.”

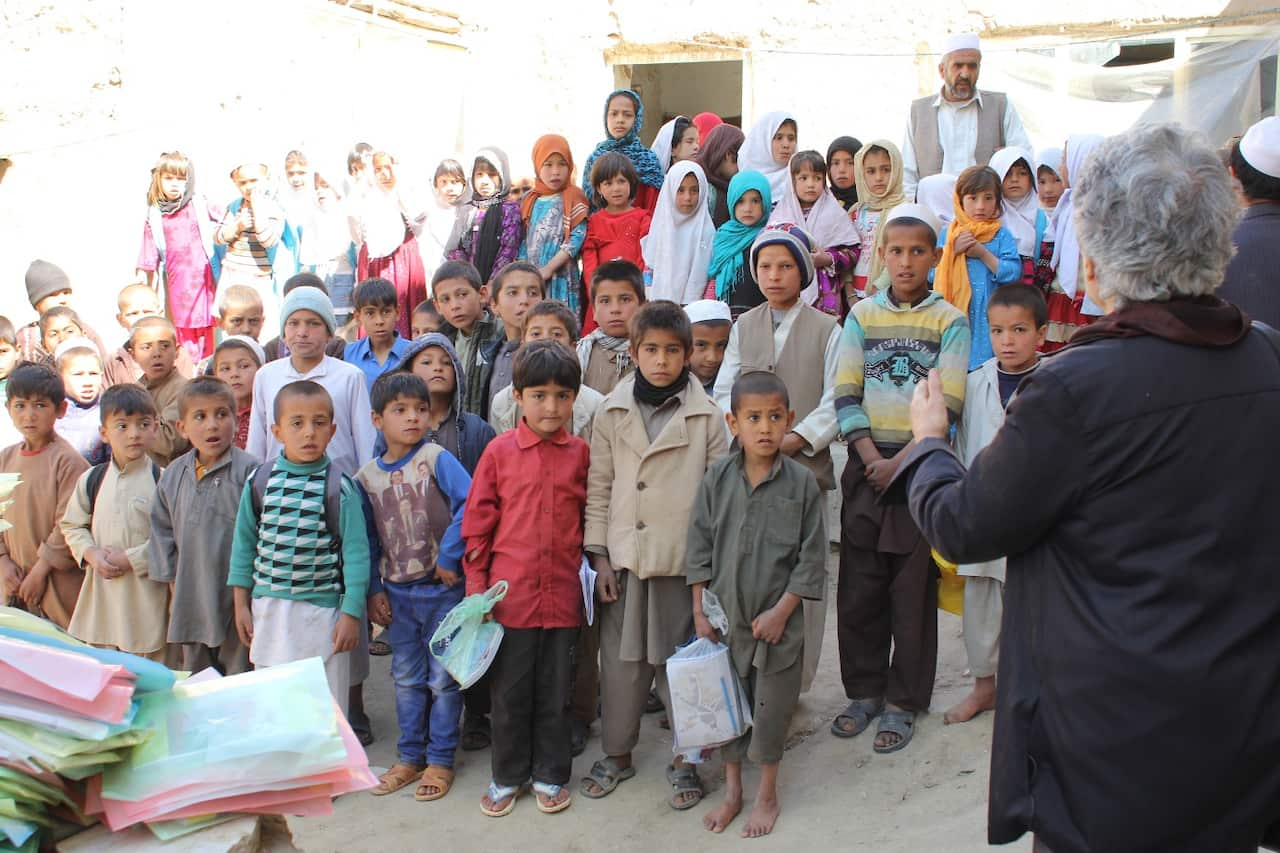

Dr Salehi visits Afghanistan every six months, and after a visit in 2002, she decided to create the Afghan Australian Development Organisation, which provides vocational training, science education, and literacy programs for women and youth in Kabul and nearby villages.

“When I returned to Afghanistan, at that point, the University of Kabul did not even have windows and doors,” she said.

“So from then, education was my focus – it is the key to peace, and we can use it to help people wherever they are.”

For the energetic retiree, it has been a lifetime’s work to bring more opportunities to Afghan people in Australia and in Afghanistan, but also to teach Australians about Afghan culture.

She knows that most people come to her restaurant for the palaw but she hopes that they walk away with a better understanding of the country she loves so much.

“I wanted to share Afghanistan’s culture with Australia, and I hope that in the future, someone will take responsibility for these things,” she said.

Would you like to share the story of a remarkable Australian? Email jessica.washington@sbs.com.au.