Australian scientists Mark Scarcella and Yi Ling Hwong have both worked on one of the largest and most expensive experiments in the world: the Large Hadron Collider.

It attempts to recreate conditions at the beginning of the universe, known as 'the big bang'.

Ms Hwong and Mr Scarcella are taking part in a new exhibit at Sydney's Powerhouse Museum showing people the science behind the Collider.

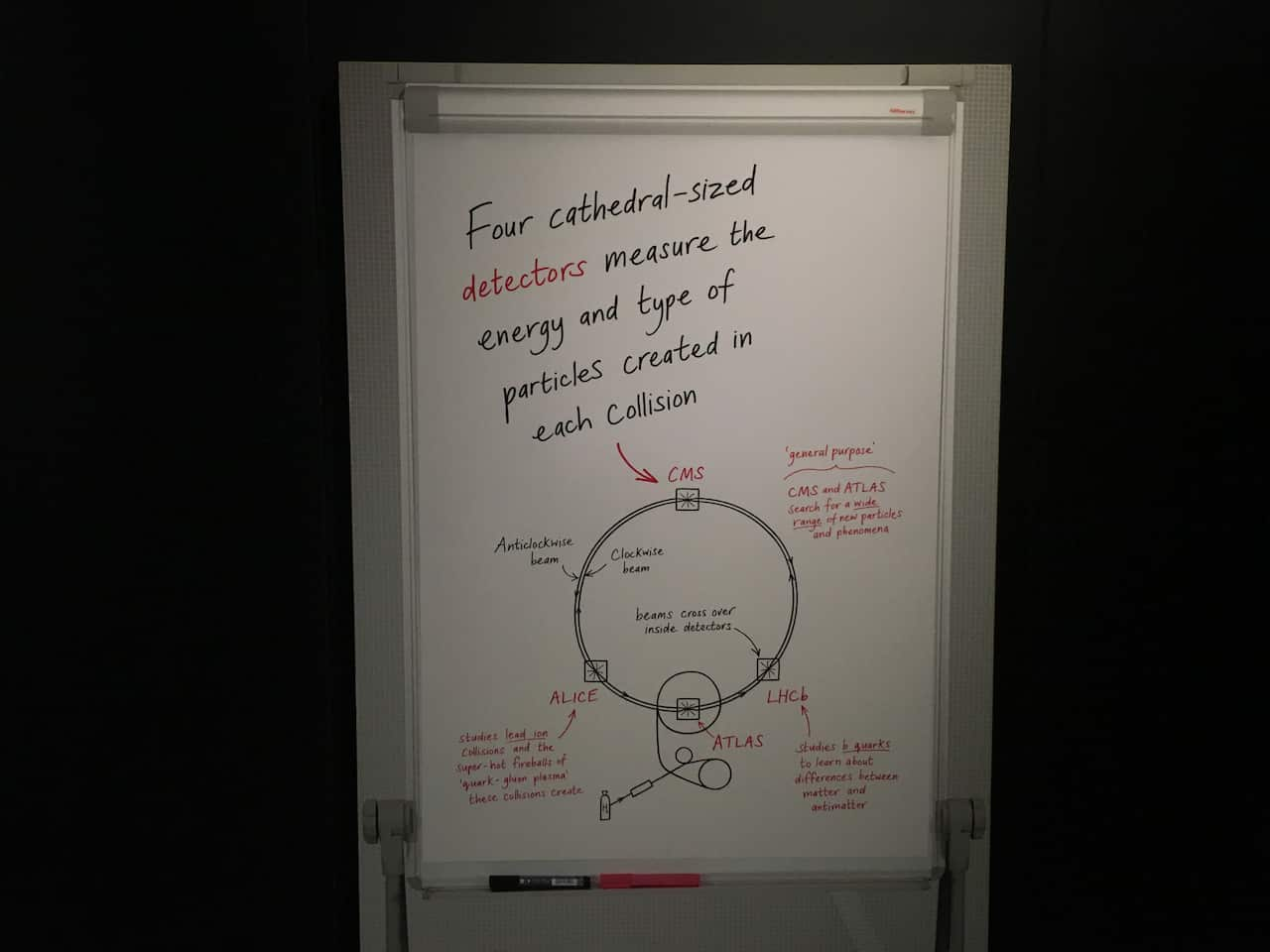

It works by accelerating beams of particles, usually protons, to almost the speed of light, and shoots them around its 27 kilometre-long circular tunnel which is buried 100 metres across France and Switzerland. Ms Hwong is one of the few female engineers at the European Council for Nuclear Research, or CERN. She has worked on the Collider for five years.

Ms Hwong is one of the few female engineers at the European Council for Nuclear Research, or CERN. She has worked on the Collider for five years.

The Large Hadron Collider is a particle accelerator - 27 kilometers long buried 100m under Switzerland and France. (SBS)

“So first of all we need very strong force and to generate this force we need strong magnets - and in order to make the magnets really powerful, we need to make them super conducting.," says Ms Hwong.

"That means we cool the magnets with liquid helium to a temperature of - 271.3 Celsius.”

Mark Scarcella is a particle physist. He analyses the data from the collisions, searching for answers about gravity, dark matter, anti-matter, and extra dimensions.

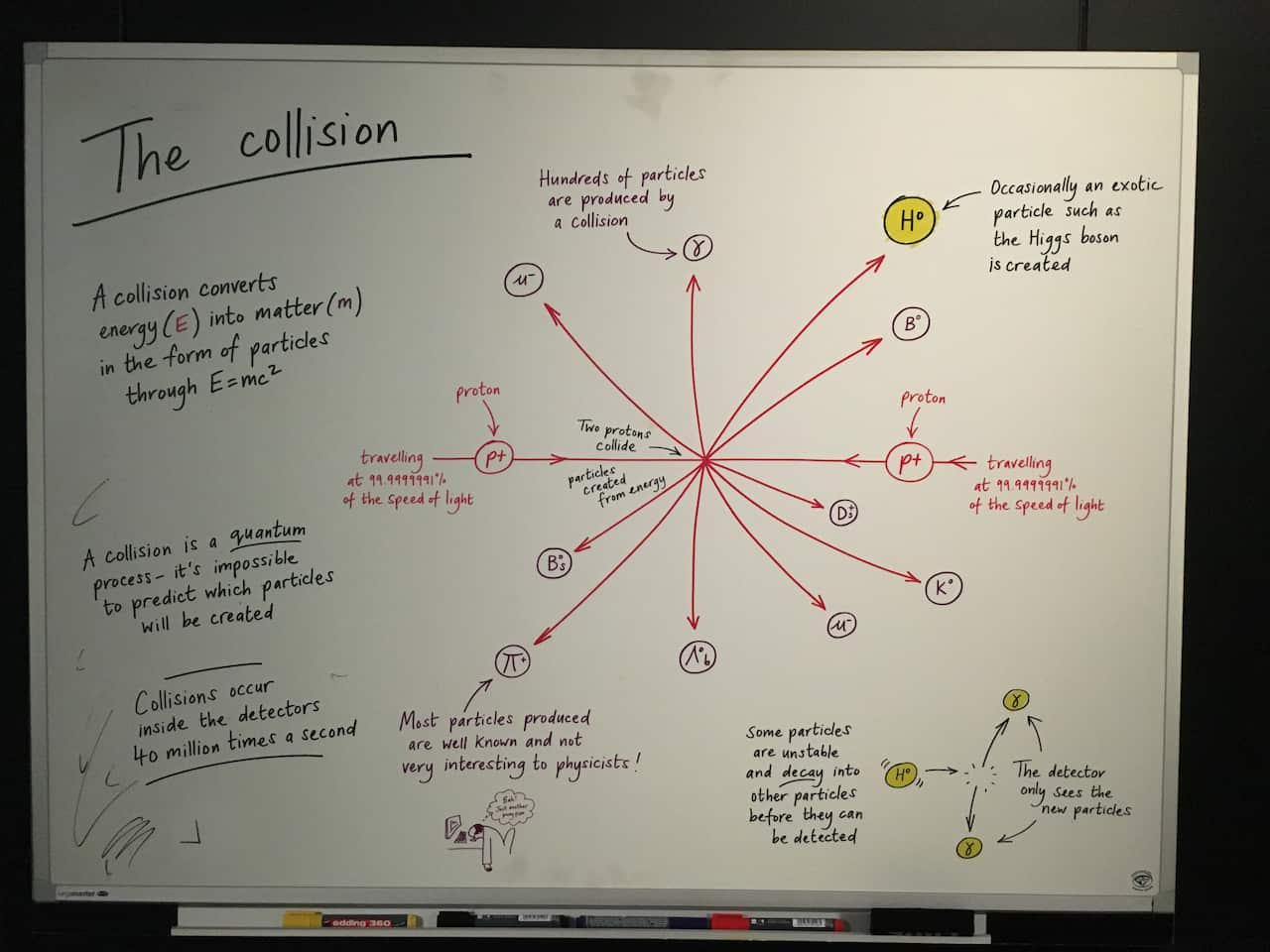

“When these protons collide, they're going extremely fast, 99.9999991 per cent the speed of light, so incredibly fast, and when they collide all of that energy can be turned into mass," he says.

"Hopefully that big mass will make something really interesting. It does explode out, like a car crash, but imagine getting all the parts from a car crash, without seeing the blueprints, or even knowing they were cars in the first place.” Physists have to sift through 30 million gigabytes of data each year.

Physists have to sift through 30 million gigabytes of data each year.

The biggest discovery was the Higgs Boson in 2012. Also know as the 'God Particle', it is responsible for giving other particles mass.

“We're not sure what's out there. Ah, dark matter, other theories like this are being looked at very closely now. But the fact that we haven't seen anything new, when we kind of expected to, is getting very interesting, and I'm quite excited to see what pops out,” Mr Scarcella says.

The Collider is now in its second round of research, and a major upgrade last year has made it nearly twice as powerful.

Ms Hwong says that level of energy -14 tetraelectronvolts - has never been a achieved before.

“So that means we are exploring new frontiers of physics like higher energy, probably new particles. People are really excited at CERN," she says.

"I'm not there, but on Facebook, all my friends are talking about it, so I can can kind of feel it even far away, from Australia.”