Twenty-three years ago today the Australian government first recognised the rights of Indigenous Australians to "possess, occupy, use and enjoy" culturally-significant land.

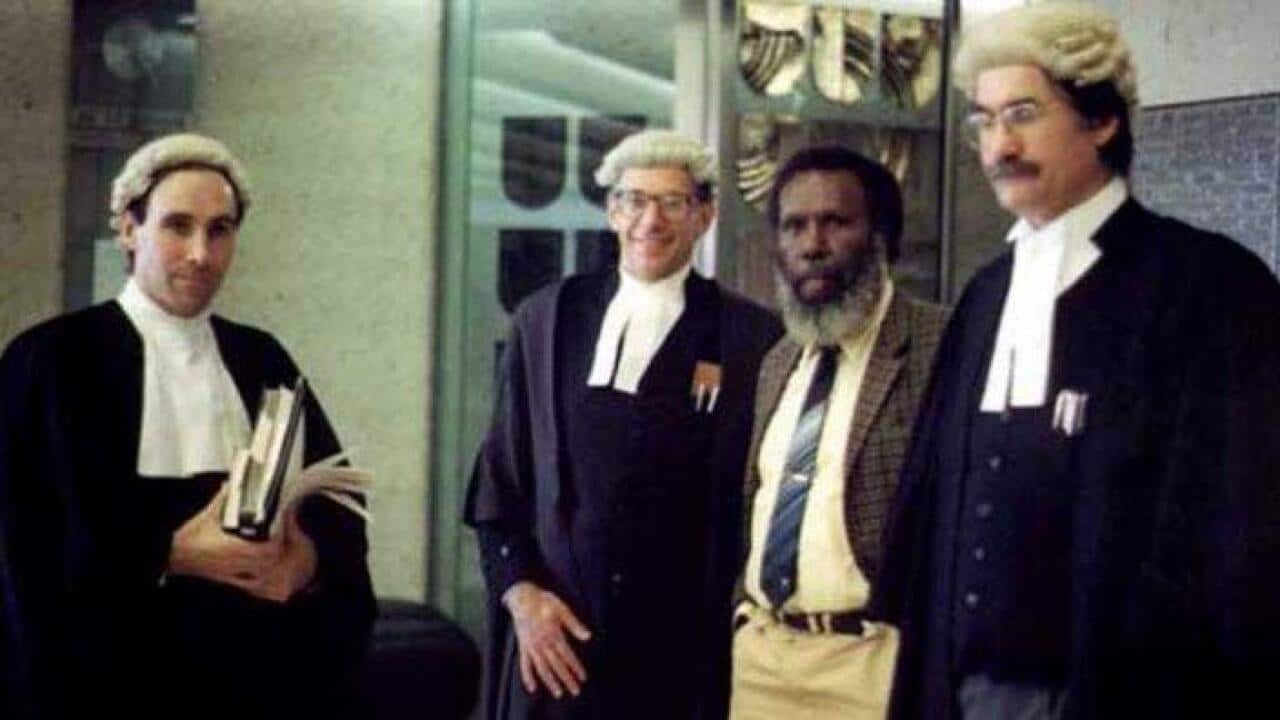

On June 3, 1992 the High Court of Australia overtuned the notion of Australia being 'terra nullius' (nobody's land) before settlement. The Mabo decision, as it become known, followed a decade-long legal battle by Eddie Mabo and several others to have their land rights recognised.

Edward Koiki Mabo was born at Mer (Murray Island) where Meriam people are the traditional custodians of the land.

Eddie Mabo, Celuia Mapo Salee, Sam Passi, Father Dave Passi and James Rice had sought a declaration that the annexation of Murray Island by Queensland in 1879 had not extinguished native ownership of land.

Sadly, Eddie Mabo did not live to witness the descion. The ruling that Meriam people did have native title at Mer, in the 'Mabo and others V Queensland' case, was made in the High Court of Australia, five months after Mr Mabo died from cancer.

The lead judgement came from Justice Sir Francis Gerard Brennan, who said the description 'terra nullius' meant colonists could legally take land, according to international law at the time. The ruling overturned the concept of 'terra nullius' and found the Meriam people did have native title rights to areas of Murray Island. It found the British soverignty enforced in 1788 still applied, meaning the land was still part of Australia.

"International law recognised conquest, cession and occupation of territory that was 'terra nullius' as three of the effective ways of acquiring sovereignty," he said.

“When sovereignty of a territory could be acquired under the enlarged notion of terra nullius, for the purposes of the municipal law that territory (though inhabited) could be treated as a 'desert uninhabited' country."

Australian Professor Henry Reynolds said the British use of the term 'terra nullius' reflected an attitude similar to other European powers at that time.

“European powers adopted the view that countries without political organisation, recognisable systems of authority or legal codes could legitimately be annexed,” Professor Reynolds wrote.

The effects of the Mabo decision continue decades later. Today native title rights exist across about a quarter of Australia.

Native title is granted when the Federal Court of Australia determines Indigenous claimants have unique ties with the land, or certain marine areas, where acts of government have not removed the connection.

Today native title exists in the Northern Territory and every state except Tasmania, where there have been no native title claims.

Western Australia has a particularly high proportion of land – 43 per cent of land in that state – recognised as having native title.

Native title exists in many areas across the north eastern region of Western Australia, the Kimberley, which stretches between south west of Broome to the Northern Territory border.

"Before Australia was settled there wasn't ownership. The land sustains you. You don't sustain the land."

The Kimberley Land Council was formed in 1978 as a political land rights organisation.

“Native title means a lot to our members of the community, it gives us greater access to land,” said KLC chair Anthony Watson, from Nyikina Mangala country.

“It means ownership, to get back to your country.”

Mr Watson said having native title gave traditional owners a say in what should and should not happen on their country.

“Like Mabo said, it’s a bundle of rights,” Mr Watson said.

He said Mabo Day was important to remember when the land rights of First Australians were recognised.

Native title does not mean areas are locked up.

Voluntary Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) can be negotiated between native title holders and others who wish to use the land or water.

People or companies may want to access the land for mining or water rights, in return for services that benefit the people living on country.

"We had an ILUA with Shire of Derby, that could expand into delivery of services," Mr Watson said.

Eddie Mabo's daughter, Gail Mabo, has been in Tasmania for Reconciliation Week.

She said Mabo Day was a turning point in this country.

"People should celebrate what the day is about, which is his achievement," Ms Mabo said.

The south west of Western Australia, which the Noongar People call 'Noongar Booja', or Noongar country, has several active native title claims.

The Mabo decision meant greater rights for the Noongar People, South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council acting chief executive officer Wayne Nannup said.

"Native Title was born out of Eddie Mabo’s actions," Mr Nannup said.

"The Noongar People of the south west are in the position they are in today as a result in part, of what Eddie Mabo started 23 years ago."

He said native title was more about taking care of the land, rather than owing it.

"It's something you've got a responsibility to look after," he said.

"Before Australia was settled there wasn't ownership.

"The land sustains you. You don't sustain the land."

Several claims in the Noongar area overlap, but they were more or less the same people, Mr Nannup said.

However, the Noongar people are not placing all bets on native title.

"We aspire to work toward self-determination for our Noongar People, this requires more than what native title can deliver for us," Mr Nannup said.