The United States' civil space agency NASA has announced plans to launch a crewed mission around the moon in April next year, although it could potentially come as early as February.

The 10-day mission involving four astronauts is part of NASA's Artemis program, the flagship US effort to return humans to the moon as early as 2027.

"This flight is another step toward crewed missions to the lunar surface and helping the agency prepare for future astronaut missions to Mars," NASA said in a statement.

The crew — comprised of three US astronauts and one Canadian — would become the first to orbit the moon in more than half a century.

"We together have a front-row seat to history: We're returning to the moon after over 50 years," NASA acting deputy associate administrator Lakiesha Hawkins said at a news conference on Tuesday.

The Artemis 2 crew comprises of astronauts (from right to left) Reid Wiseman, the mission's commander who last flew on a Russian Soyuz rocket to the International Space Station in 2014; Victor Glover, the pilot who flew to space in 2020 on a SpaceX ISS mission; Christina Koch, a mission specialist who flew on a Soyuz ISS mission in 2019; and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen, another mission specialist who will fly to space for the first time. Source: Getty / Austin DeSisto / NurPhoto

Multiple setbacks have delayed Artemis 2 but Hawkins says NASA intends to keep the commitment of an early 2026 launch.

According to NASA, the Artemis project's goals are to "explore the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and to build the foundation for the first crewed missions to Mars".

A 'free ride' and a 'slingshot'

Richard de Grijs from Macquarie University's Astrophysics and Space Technologies Research Centre likened the Artemis 2 mission to "a test drive of a new car".

"This is a test drive of a new spacecraft that's meant to bring humans back to the moon. But this is the first time, so they'll do a fly-around rather than a landing," he told SBS News.

"They will go up into orbit, they'll circle the Earth once, and then — if everything goes well, because tests will be done, of course, during that orbital journey — they'll set course for the moon."

"This is done in such a way that they'll use, in essence, the moon's gravity to get a free ride back — just in case anything happens," he said.

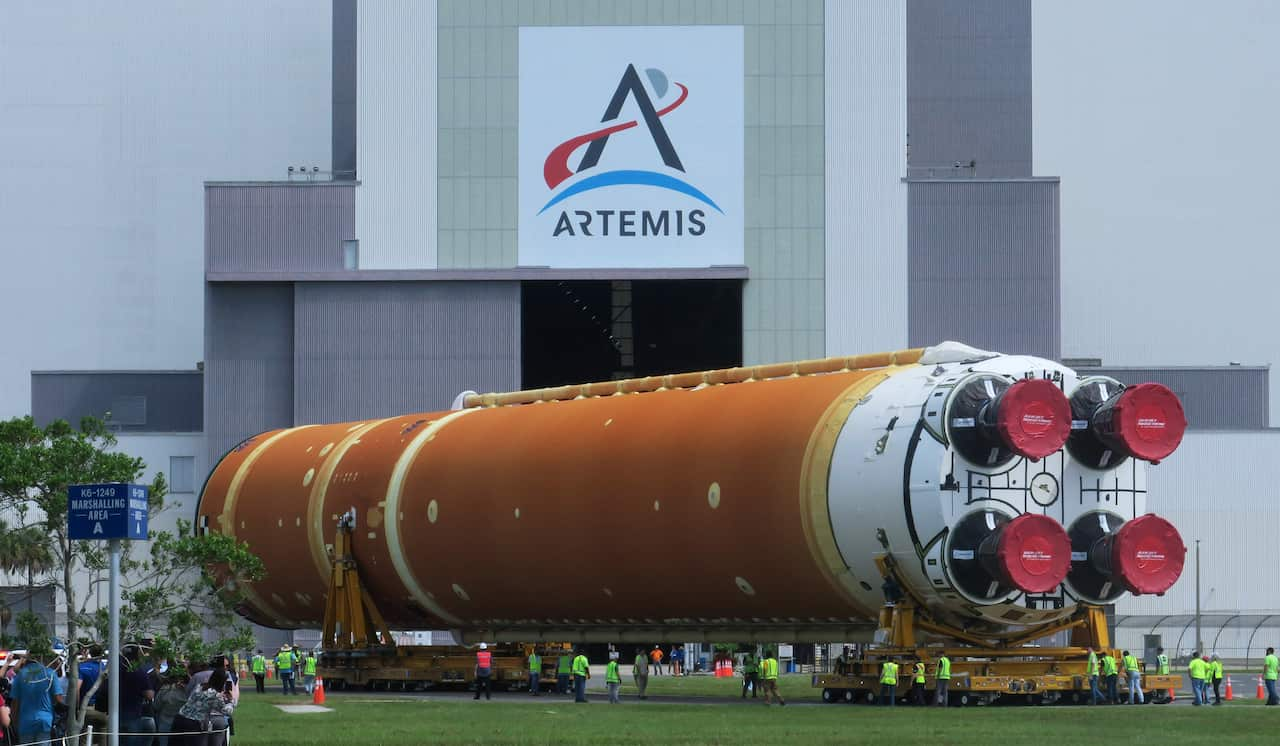

Workers transport the 64m tall SLS core stage for the Artemis II moon rocket at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida in July last year. Source: Getty / Paul Hennessy / Anadolu

Lead Artemis 2 flight director Jeff Radigan has said that the mission will take the crew at least 9,000km past the moon.

"So, the moon's going to look a little bit smaller," he said.

NASA has said, should the mission go according to plan, the Artemis 2 spacecraft will land in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego.

'The Apollo program for our era'

The last time humans landed on the moon was December 1972 — the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, a series of space flights undertaken by NASA between 1961 and 1972.

It was the sixth time humans had set foot on the moon, with the first human moon landing being that of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin in July 1969.

"[Artemis] is the Apollo program for our era. That's how you could characterise it. It's a big, bold thing," de Grijs said.

"They want to bring people back to the Moon, not just for three years as they did during the Apollo era, but for a more sustainable presence."

Jonti Horner, an astronomer based at the University of Southern Queensland, characterised a permanent human presence on the moon as "a stepping stone to the rest of the solar system".

"One of the goals is this idea of having a permanent presence at the [moon's] South Pole, having a station in orbit, and also using it as a place where we can then build to go out to Mars or to go to the asteroids or wherever we choose to go," he said.

Horner said the program was likely to have "a huge amount of benefit" to science.

"I think once we can get people to the moon, or to Mars down the line, that will open up huge avenues for exploration because it's a lot easier if you are there in person to walk around and go: 'That looks interesting. I'll go look at that'."

"You'd learn more about Mars by sending a geologist there with a hammer and giving them one hour than we've learned from all the years of robotic spacecraft going there."

De Grijs said one of the key scientific benefits would be the ability to analyse large amounts of lunar soil.

"At the moment, we've had a few sample return missions, most recently by the Chinese. But what they bring back is a relatively small volume of material, often no more than one or two kilograms of regolith, which is the lunar soil," he said.

A 3.2-billion-year-old rock of sintered lunar soil collected by Apollo 15 inside a pressurised nitrogen-filled case. Source: AP / Michael Wyke

"And so, depending on where you are on the moon, different soil samples, regolith samples, will be able to tell you a lot more about the origin of the moon. And so you need to sample much more than just a few kilos here and there."

According to NASA, "several theories about our moon’s formation vie for dominance" but nearly all agree that the moon "was born out of destruction" — most likely an object or series of objects crashing into the Earth and flinging molten and vaporised debris into space around 4.5 billion years ago.

'Some very difficult conversations'

De Grijs said that, while scientific progress was definitely a key motivator of the Artemis program, "in the end, it's also about resources".

Mining of mineral resources was "definitely on the horizon", he said, but water was likely to be the first resource extracted.

"Over the last couple of years, there has been a lot of interest in the southern hemisphere of the moon, particularly south of the moon's polar circle, where there might be frozen water that could potentially be used for resources for more permanent settlement or even as a reservoir for further journey into the solar system," he said.

Horner said this water could be "really valuable" to provide fuel for rocket launches.

"If you can extract that from the south pole of the moon, launch it to the station orbiting the moon ... you can use that to fuel all your missions and save a lot of money."

However, Horner expects extraction of moon resources to trigger "discussions in the decades to come about the balance between our commercial use of the moon and what people on the ground see when they look up".

"For different cultures around the world, the moon is very sacred," he said.

"And so there's going to be some very difficult conversations and hopefully some really good understanding reached, to ensure that we get the best for everybody with a minimum harm."

A new space race?

China also has a space program that's targeting 2030 at the latest for its first crewed mission to the moon and also plans to eventually establish a base on the moon.

US President Donald Trump, who announced the Artemis program during his first term, wants the US space agency to return to the moon as soon as possible and, during his second term, his administration has piled pressure on NASA to accelerate its progress.

The Trump administration has referred to a "second space race," a successor to the 20th-century Cold War competition over spaceflight technology between the US and the Soviet Union.

"There's definitely a sense of competition there, and that done rightly is not actually necessarily a bad thing," Horner said.

"It can be a real driver of technological development and of pushing the boundaries to what we can do," he added.

"I'd much rather countries be looking at exploring as a way of showing their might rather than flexing their military muscles."

De Grijs, who is also executive director of the International Space Science Institute–Beijing, says that it may be "seen as a space race from the US side", but that's not a feeling shared by China.

A Yaogan-45 satellite blasts off from the Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site in Hainan Province, China, on 9 September. Source: AAP / Yang Guanyu / EPA

"[The Chinese] work on a five-year schedule. They have five-year plans, and every five-year plan, they have certain things they want to achieve, and they go slowly but steadily, and they build up their expertise and their innovation.

"The Chinese have a plan to also go to the moon, but I don't think they're going to be rushed by what the Americans are doing."

— with additional reporting by Reuters and AFP