In the hope of settling himself, Andre leaves the city behind and journeys to what he thinks is the empty heart of Australia. Except, as he discovers, it isn’t empty at all.

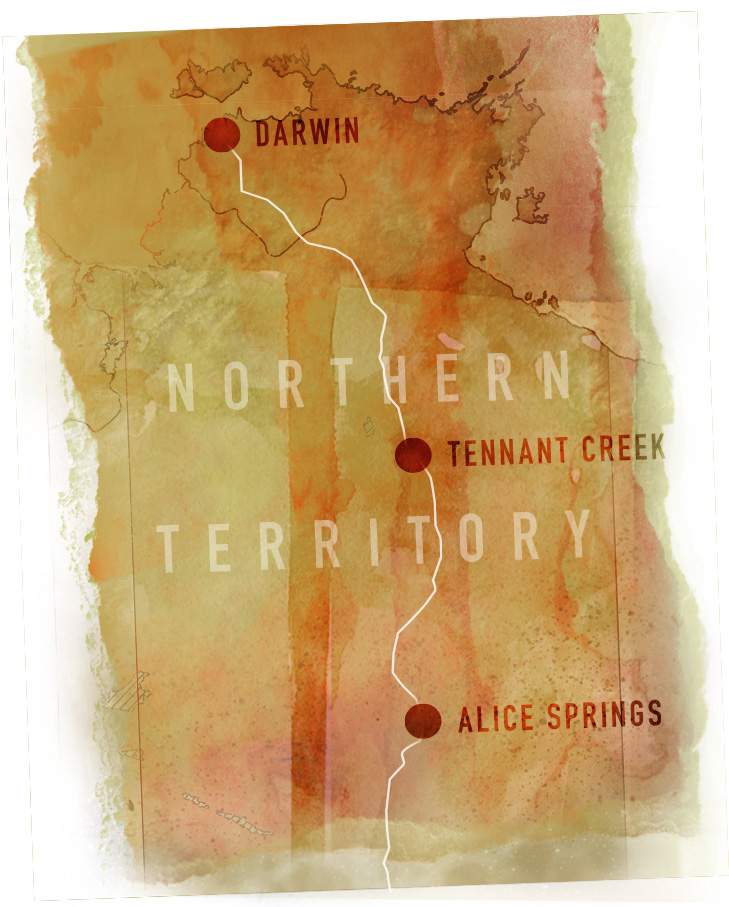

Tennant Creek is a thin sliver of houses and pubs scraped onto the sides of the Stuart Highway, a road stop for grey nomads and European backpackers between Alice and Darwin.

Like those travellers, I’ve been feeling restless lately – hemmed in by the city and frustrated by the news – so I’ve journeyed, in hope of settling whatever it is that unsettles me, to what I’ve always imagined to be the empty heart of Australia. Except that it isn’t empty at all. 100 kilometers down the highway from Tennant is Muckaty Station, where the Federal Government wants to build a nuclear waste dump. But Muckaty – like all the land around here – is a place full of stories and sacred sites. The two lawyers I’m travelling with are working with a group of traditional owners who oppose the dump. As I’m dropped off at a hostel on Tennant’s outskirts, I can see the endless Barkly scrub springing up just beyond the hostel’s fence line, and I imagine myself travelling on country with the traditional owners, learning their old stories – a neutral observer.

His breathing comes laboured and shallow. I’ve never seen someone so visibly sick outside of a hospital

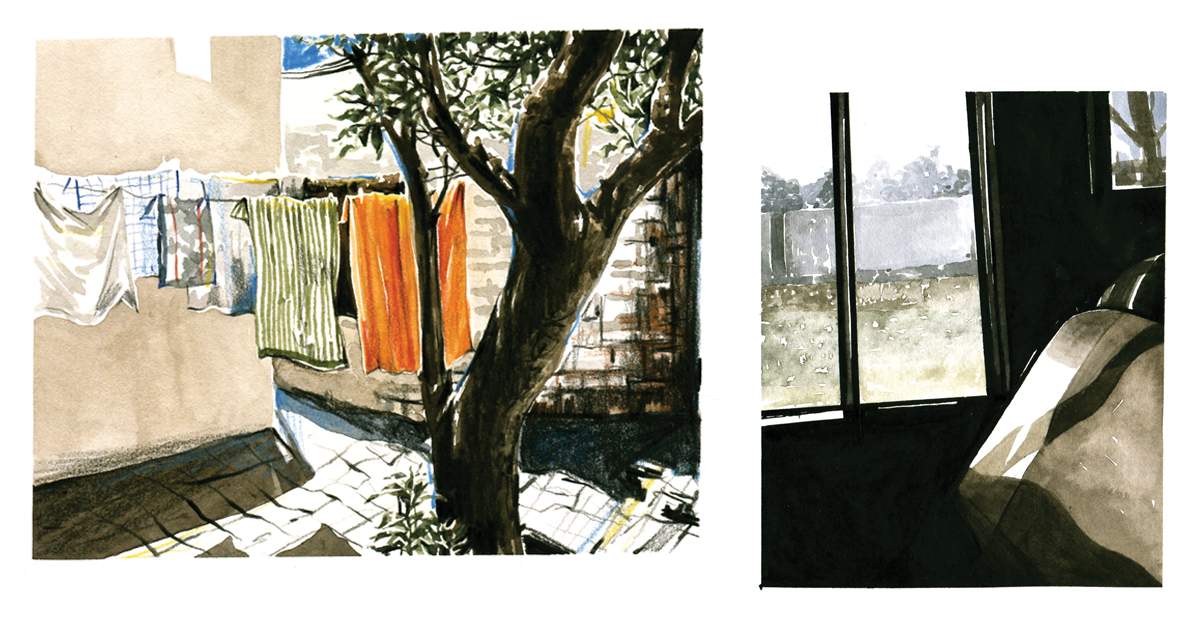

I meet Jim a couple of days in, on my way back to my shoebox room from the hostel kitchen, which smells of turps and rotting vegetables. He is sitting on a thin, fragile looking wheelchair-cum-walking frame, gazing out at the big sky and the boundless savanna which is surprisingly green – in my ignorance I had expected the Mars-red outback, but of course the rains have just been and the prickly grass is full of unexpected life. I nod as I pass him, thinking of the interviews I need to transcribe before the lawyers pick me up for another day’s work.

He shows no sign of having seen me or my nod, but just as I reach for the door Jim speaks.

"What’s your name", he says, still looking out at the scrub.

I tell him, my hand on the door knob.

"André, that’s a beautiful name", he says.

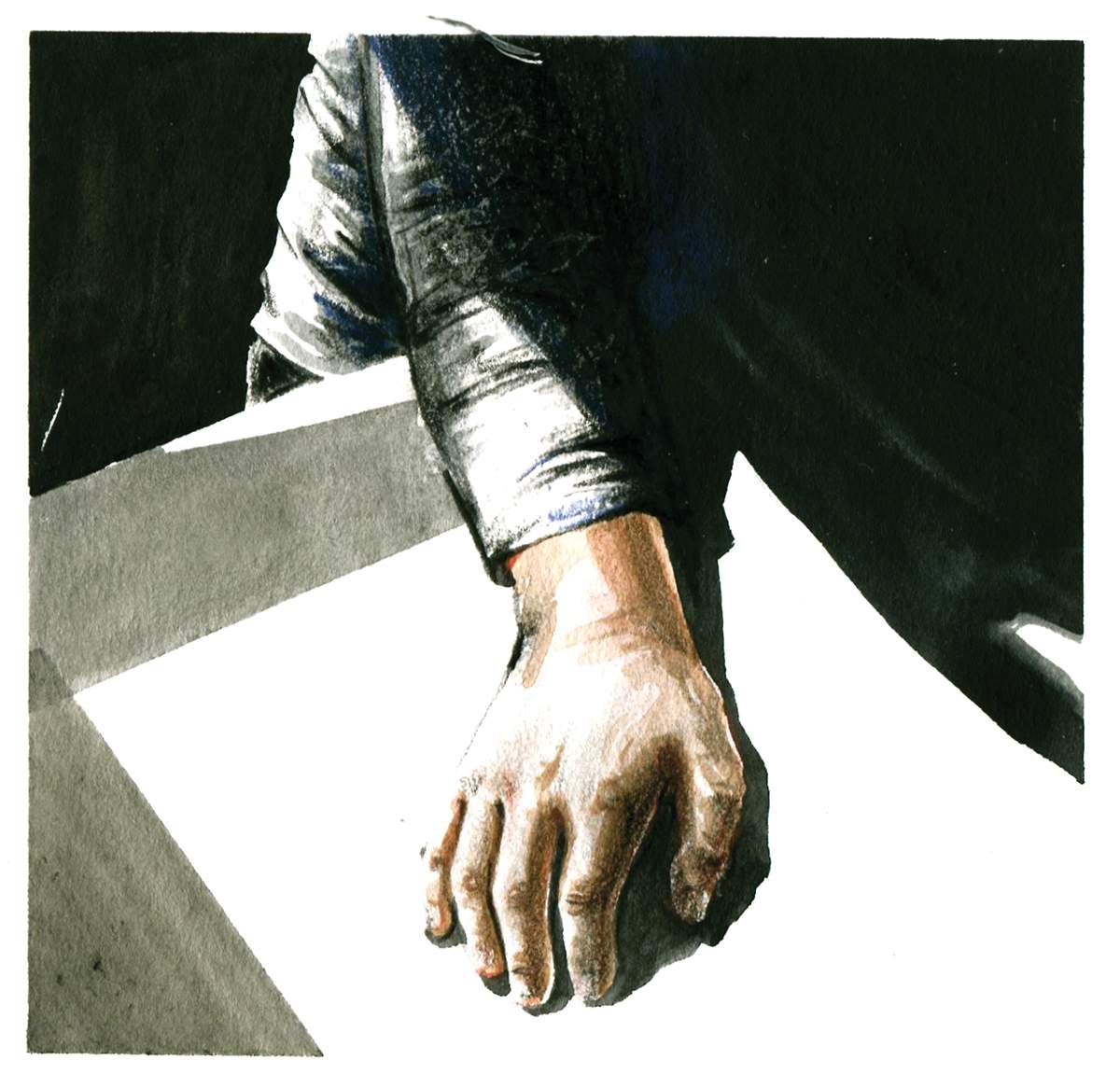

I have to turn around to hear him because his voice is so faint and only then do I see him properly – half his face is taken up by an enormous goitre, a heavy bag of excess skin hanging down from his left cheek. His hair is all gone but for a wisp of snow-white strands plastered across his liver-spotted skull. His breathing comes laboured and shallow. I’ve never seen someone so visibly sick outside of a hospital.

"My name’s Jim", he says. "Not nearly as beautiful as yours."

Not knowing what else to say I tell him how my dad is a Francophile, how after the war he lived in France and how he always wanted his Vietnamese sons to speak French, even though we lived in Bundoora, an outer northern suburb of Melbourne that was about as far from Paris as you could get.

I’m already anxious, exposed, vulnerable in a way that I’ve always hated.

"I never learnt", says Jim. "I should have, being Canadian. But I met my wife when we were both very young. And she was Australian, you know. So I moved to Adelaide, when I was 21. I never went back home."

A dozen budgies squawk and titter in their cages, waiting for Tony, the hostel’s owner-operator, to come and feed them.

"Can you help me, André?" The question catches me off guard, and I find myself saying, "of course, of course – what is it?" But even as I wait for his reply I’m already anxious, exposed – vulnerable in a way that I’ve always hated.

Now I think we were afraid, our whole lives we were afraid.

"Thank you", says Jim, and those two words, thank you, are filled with immense relief. He settles back in his seat. "I was very afraid", he says. "I didn’t know if I would meet anyone here, and I was afraid that if I didn’t – what could I do, but wait?"

I nod, a little distractedly, still waiting for him to reveal what he wants from me.

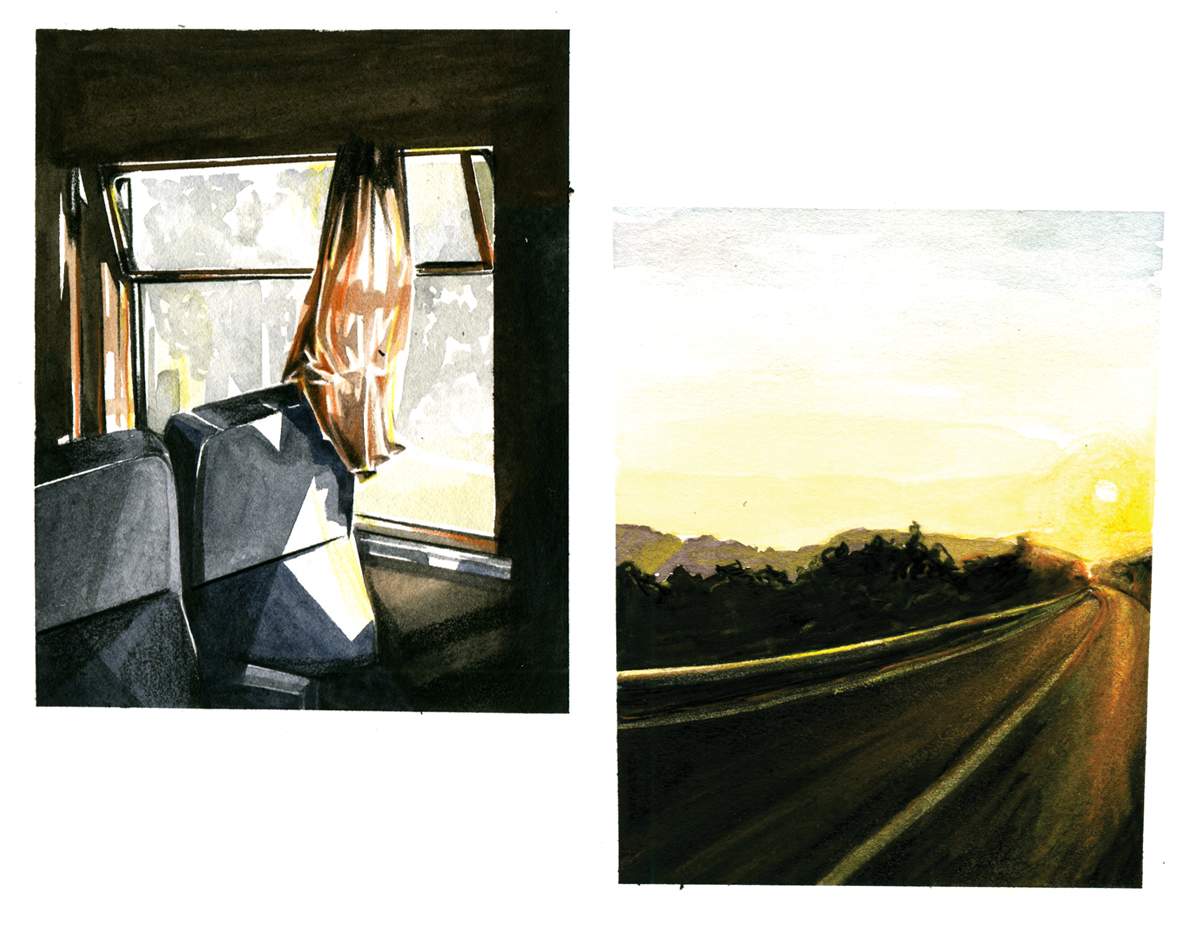

"You see, my wife died", says Jim. "Two years ago now. I got my diagnosis not long after that" – he waves a bony hand at the goitre – "and they had all sorts of treatments lined up for me, hospital visits, nursing homes. You can imagine. But I couldn’t bear the thought of it, the tubes and the gowns and the kind smiles. And besides, my wife and I, we had always wanted to travel, to see more of Australia. In all our years here we had only been to Sydney twice, Melbourne once. But we never found the time to do more. Now I think we were afraid – our whole lives we were afraid, but I can’t remember what we were afraid of. I only remember that we wanted to go and we never did. And then she died, and the doctors said I would die soon too. So I bought a bus ticket – it’s a marvellous service, the Greyhound buses. They can take you anywhere, anywhere at all, right across the country. I’m trying to see as much as I can, to make up for lost time. And I see things, through the bus window. Wonderful things."

I can hear Tony feeding the budgies, chirping back at them from his motorised scooter, his voice a gravelly drawl, "here Rosie, here, Rosie." I remember my own lonely bus rides, when I was eight, shuttling between Melbourne and Canberra, where my dad had gotten a job for the year. They had seemed endless, those trips, and the indifferent passengers had seemed strange and overgrown to my child’s eyes – sweaty and impatient to get to their destinations. I want to tell Jim about those memories, but I can’t find the words.

"So you see", says Jim, "I’m on my way to Toowoomba. But I don’t know how to get to the bus stop. I was hoping..."

In my relief, I say again, of course, of course.

I imagine myself being the kind of person who doesn’t let someone die alone.

When the lawyers arrive to pick me up Jim is waiting with me in the carpark, all his possessions folded up neatly and packed away – his small suitcase under his seat, a little cloth bag hanging off the back of the frame. In the car, he tells us that the bus to Toowoomba won’t arrive until 10 or 12 hours from now. But he’d rather wait at the depot, just to be sure. When we drop him off at the tin shed station Jim keeps thanking me as if I’d done some great deed. But it seems churlish to do anything but accept his thanks. When he asks if I might come visit him before the bus arrives – friendly faces are few and far between, he says – I say yes once again, of course.

As the lawyers and I do the Paterson Street crawl – cruising Tennant Creek’s main drag in the hope of running into a witness for the upcoming trial, or someone who might know where a witness might be – I keep thinking about Jim, riding the Greyhounds, looking out his window and waiting to die. There was no family left, he’d said. He and his wife had never had children. And while she’d been alive, that had been enough. But now, it’s like he said – what else is there to do but wait?

I imagine myself returning to the depot, Jim’s face when he sees me. I imagine buying a ticket for Toowoomba – why not – and settling in to my seat next to Jim. It’s a long drive, from Tennant to Toowoomba – hours and hours, enough time for day to turn to night and back again – but the journey passes quickly in easy, deep conversation. Jim has a lot to say, I imagine, a whole lifetime of words and memories left unsaid. I imagine myself being the kind of person who doesn’t let someone die alone.

He’d asked me about myself and I’d told him the usual things - which is to say, nothing at all.

The lawyers drop me off not far from the bus depot. The evenings here are cool and the sky is awash in pinks and purples. I feel like going for a walk but I’m not quite comfortable; I haven’t seen any evidence for Tennant’s reputation for violence, but I don’t feel like testing my luck. And then there was the long conversation with Michael, one of the traditional owners at Muckaty. I don’t belong here – not that he ever said so, not in so many words. But it was the truth: a southerner, a whitefella – or at least, not a blackfella, which amounts to the same thing. Doubly unbelonging.

Maybe it’s that feeling of dislocation, why I don’t go see Jim at the depot. But that’s probably just an excuse. Those sorts of stories – getting on the bus, listening to an old man’s dying words – they only ever happen in my imagination. When the bus to Toowoomba barrels into town down the Stuart Highway I’m already halfway back to the hostel, a cardboard container of cheap noodles from Woks Up in my hands. I think about our conversation while we'd waited in the hostel carpark for the lawyers. He’d asked me about myself and I’d told him the usual things – which is to say, nothing at all: about life in Melbourne, about my devout Catholic family, and the writing that took me to far flung places like Tennant. He’d smiled at that, his whole face brightening so that for a moment the goitre and the rheumatic eyes and the faint sour smell of illness fell away, like clouds momentarily clearing to reveal the happy sun.

By the time the bus leaves, with Jim and his wheelchair and his little suitcase and his cloth bag stowed aboard, I’m sitting in my shoebox room, watching an episode of The Wire on my laptop and slurping down the greasy noodles with cockroaches and lizards for company.