Forced to become a child soldier, Julius Achon survived to run at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Now a government minister in Uganda, he is mentor to an Australian who will compete in Rio. But there’s more at stake: a plan to bring hope and food to Africa.

It’s lunchtime on a crisp, wintry day in a comfortable southern suburban Sydney home, just weeks out from the Rio Games.

Olympic athlete Eloise Wellings has risen at dawn, readied her daughter India, 3, for kindy, run 16km and done a one-and-a-half hour gym workout. Before she can begin to explain how the people in a small, remote corner of Africa inspire her running, she ducks upstairs to peep at the Ugandan politician asleep in her spare bedroom.

“I have to check that Julius is breathing,” she says. Her husband Jon has phoned to remind her that deep vein thrombosis is a risk, given their friend Julius Achon has flown from Kampala via Dubai the night before.

She tiptoes past the wooden cross in her first floor window and finds Achon lying stock still. He is a slight man of trim figure, who bears symbolic scars nicked in his cheeks by a razorblade when he was a baby – marking him out in Uganda as a member of the northern Lango tribe.

She returns to her kitchen, relieved that she has detected a shallow breath.

To the Wellings family, Achon is a precious visitor. This is his sixth annual trip as charity partner and sporting mentor to Eloise. They didn’t know him when he first came to Australia as a semi-finalist for Uganda in the 1500m track event at the Sydney Olympics.

Usually, during these visits, Wellings and Achon work together to gee up their supporters who run in the Sutherland to Surf and other athletics events, raising money for their Love Mercy Foundation, which helps Ugandan orphans and families.

Watch Julius Achon tell his story.

But this time, the visit is rushed, frenetic and short, because each is about to face a huge test in public life.

For Wellings, it is about running. At age 33, after years of being dogged by injury, she believes she has her best chance yet of winning an Olympic medal. She is now fine-tuning her body to represent Australia in Rio at the 10,000m race on August 13, and the 5000m event on August 16.

He was kidnapped at age 11 and made a child soldier by Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army.

Her big rivals will be African runners from Kenya, Ethiopian, Tanzania and Uganda. “I’m not afraid of them. I’m not intimidated by them,” she says. “I think I’ve got enough experience now to know that they can be beaten, but they just have to have a bad day and you have to have a good day.”

For Achon, the big challenge is to make a difference for the 200,000 people who live in his remote rural province of Otuke, as their newly elected member of Parliament.

At 39, he still feels lucky to be alive and running, because he didn’t think he’d live when he was kidnapped at age 11 and made a child soldier by Joseph Kony’s notorious Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

Asked by local Otuke leaders to become their voice in Parliament, he threw in his lot with President Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement.

“Education is the main thing,” Achon says. “There’s money, but money doesn’t go in the right way.”

“In Africa when you need an easy life, you have to go with the ruling party,” says Achon. “And me, mostly working with foreign people, it’s so important so they don’t look at it that I’m getting sponsored to overthrow the government. If I had gone with the opposition, I wouldn’t get too much attention from the Government, either, to help the community.”

Earlier this year, he beat his nearest political rival by 11,000 votes to win his seat. He has already been appointed chair of Uganda’s parliamentary committee on education and sport.

“Education is the main thing,” Achon says. “If you look at women in my village, none of them ever went to school… I will work hard to debate about better education and health, because we are far away behind. There’s money, but money doesn’t go in the right way.”

“My district is always being forgotten, because it’s remote and we never had a representative who talked about our district. They’d come into the capital city, Kampala, and forget. Even when listing the district, mine normally don’t appear in the budget, because nobody talks about it in the parliament,” he says.

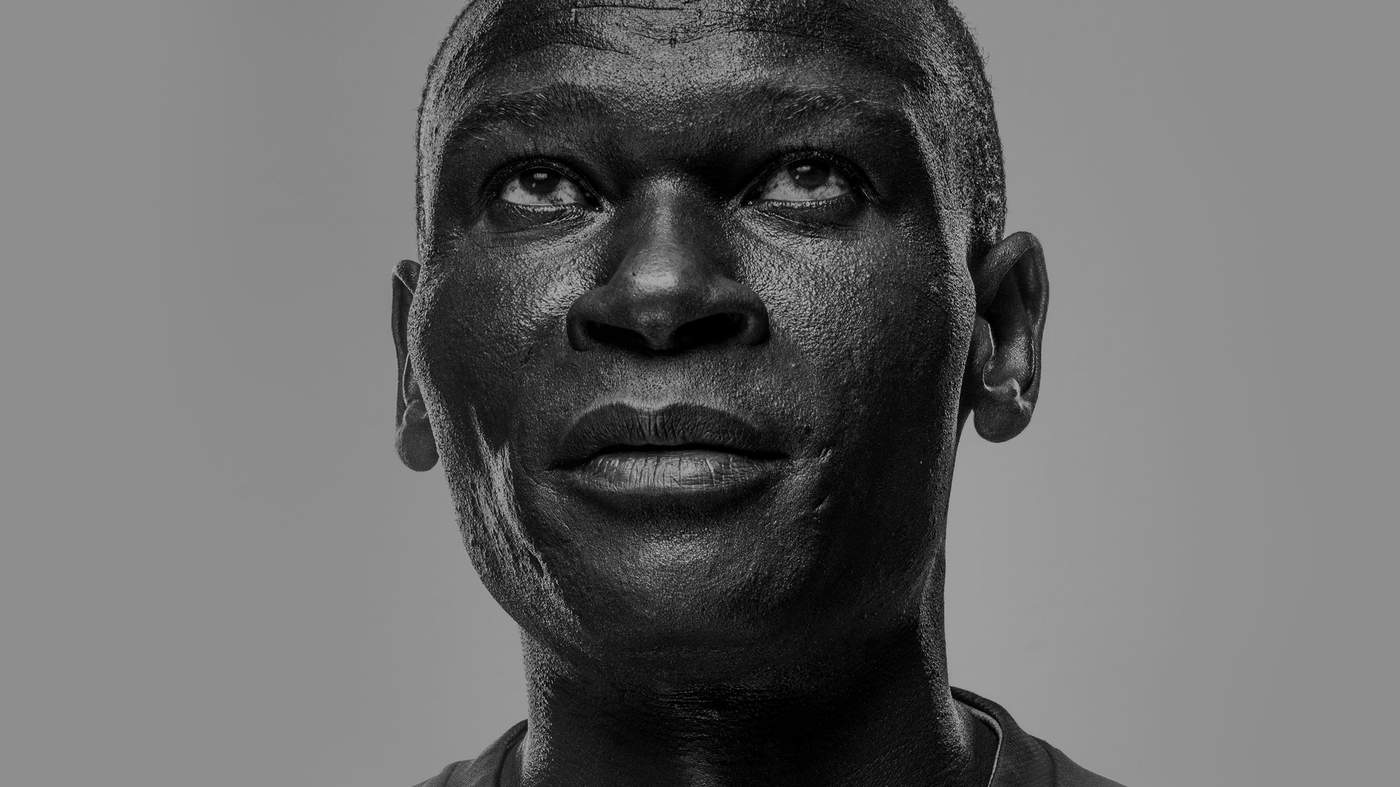

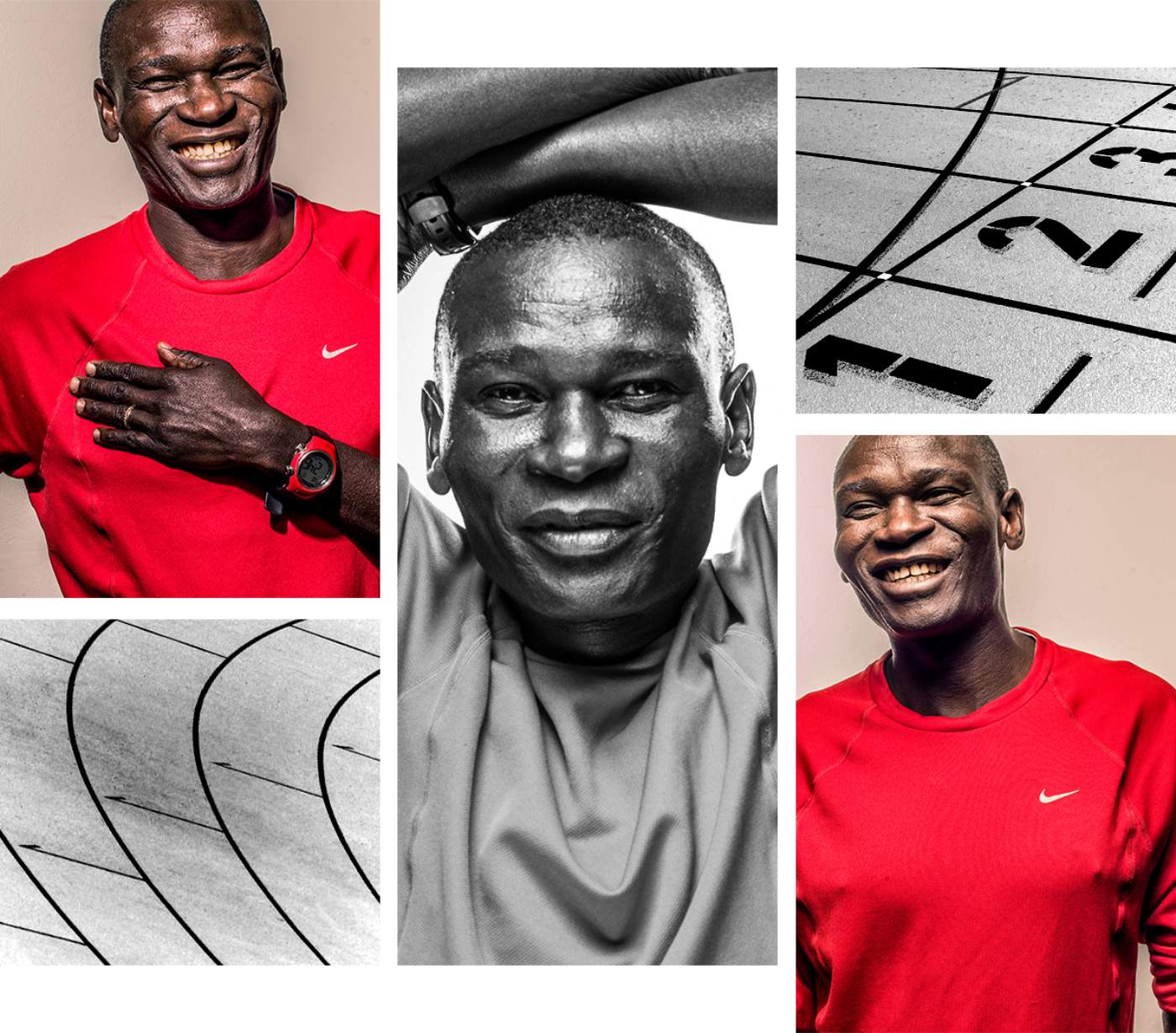

Survivor, runner, mentor: Julius Achon.

These two runners who have transformed each other’s lives – and through that, thousands more – met eight years ago at an athletics training camp in the US city of Portland. Wellings says they connected through a love of running and of faith. Both are devout Christians.

Wellings had been on a quest to win a medal for Australia at the Olympics since childhood, but she was in a bit of a bad way. Sheer ability and hard work had led her to qualify at 16. But she missed three Olympic Games in a row because of repeated stress fractures, her body weakened by an eating disorder acquired at age 13. When she met Achon in Portland, she was trying to rehabilitate her injured foot.

Achon helped her to overcome her tribulations by telling her his story, which he recounts for SBS: “In 1988, when the rebels have captured us, I was still young – I was 11 years old. I knew that was the end of everything or I would die, because usually people who are taken by the rebels rarely survive. And your parents would lose hope that you never come back.

“There was no transport… I ran 72km to a town called Lira.”

“But it was through God’s grace that I escaped when the government plane went to fight the rebels. That’s when I had a chance, so I escaped. But on the way, some of my friends, nine of them, were killed by the plane and six of us still survived. I made it home. So …God had a plan for me… [being] tortured in the bush, escaping.”

Young Achon made the 300km trek back to his northern village of Awake, determined to get an education, but his father couldn’t afford his secondary school fees of $5 a semester. So he entered a running competition for a scholarship, practising barefoot over 800m, 1500m and 3000m.

On competition day, “there was no transport… I ran 72km to a town called Lira,” he recalls. He won all three events and, with that, the scholarship to attend school in Kampala.

Aged 17, he represented Uganda at the World Junior Athletics Championship in Lisbon, winning gold in the 1500m event. This gained him a running scholarship to a US university and he went on to compete at the Atlanta and Sydney Olympics.

But a dark shadow kept Achon from the Athens Olympics in 2004. His mother Kristina was shot by the LRA. Over three days, without medical help, she bled to death.

Achon spent 15 years in the US, but after his mother’s death, he made a commitment to help rebuild war-torn Otuke. He raised funds from American donors, including his sponsor Nike, to build a hospital there named Kristina Health Centre, in honour of his mother.

He decided to care for 11 orphans whom he found hiding beneath a bus.

At first, locals paid their consultation fees with chickens. This was a Third World solution to deal with bringing home the First World benefits which Achon coveted when he went to live in the US in 1995.

“The first thing I asked myself is, how can I have such a thing put into my village – the hospitals, the schools, people have jobs, people have access for everything, clean water? So that’s what came to my mind. It became a dream,” he says.

Achon took on other responsibilities. In the year before his mother died, during a visit home, he decided to care for 11 orphans whom he found hiding beneath a bus.

Those orphans were to touch Wellings’ heart. Achon recalls: “When I met Eloise in 2008, she was talking about her leg’s [being] injured.

Best chance yet: a resurgent Eloise Wellings will target gold in Rio.

“I told her in Africa that’s very minor. ‘If I tell you my story, that I was abducted, I ran to win scholarship and my Mum was killed and I was still taking care of 11 orphans, it’s tougher than your injury. This is something you can work out how to get there within a few days.’

“And she was ashamed when she heard this story. I think from that time, she’s been more straight and has not got an injury. She remained happy from that time. And now her desire is to run for the charity, to run to help the community in northern Uganda.”

Wellings, her husband and her parents-in-law first visited Uganda five years ago, to attend Julius Achon’s wedding to his wife, Grace. It was an unusual marriage; by tradition, he says, people from his northern tribe rarely married the relatively rich and more powerful Bantu people. It started something. His brother Jimmy later married a Bantu woman, too.

“If a woman is educated, she has more dowry,” Achon says. “Or money given in the name of cows. Mine was $2000, which would have been seven cows. In the centre [of Uganda], they rarely keep cows. But my brother Jimmy took live cows. Seven… in a truck,” he says.

Wellings remembers that one of her most emotional and vivid memories on her first Ugandan trip was meeting the shy orphans in Julius’s care. She was taken with one of the older girls, Sarah.

“I noticed every now and then that when she spoke, it’s almost like she held her breath,” recalls Wellings. “She gasped, went ‘ungh’ inside the conversation. It didn’t matter what we were talking about. She’d go ‘ungh’.”

“It wasn’t till later on, when I asked Julius did she have a problem with breathing, and he said it’s really common among people who had suffered trauma… It was a post-traumatic stress response.”

“As shocking as that was, and as hard as it was to hear their story and to meet those kids, they were the lucky ones,” she says. “They were the ones that Julius had said ‘come home with me and I’m going to go back to America and run on behalf of you and send that money home so that you can be cared for’.”

Wellings had enjoyed a comfortable urban upbringing and had never seen such poverty. Her father was a Commonwealth Bank manager and her mother a schoolteacher of English and French. She was born in New York, she says, “in the concrete jungle where dreams are made of, as Alicia Keys sings it”.

“I wanted for nothing, basically,” says Wellings. “I had my first shoe sponsorship when I was 16, when I started running really well and Julius was running barefoot. I’d get home from school and have half a dozen pairs of brand new running shoes waiting for me.

“It wasn’t until Julius made the world junior championships that a friend lent him a pair of shoes to run in and he ended up winning gold.”

Although Wellings was raised a Catholic, she declares, “I became Christian when I was 16. It was a real faith awakening, a real pivotal moment in my life.”

She goes to an evangelical church and believes God has planned her life, as the Bible says, right down to the number of hairs on her head. She and her supporters found the “Love Mercy” name of their charity in the scripture passage, “For what does the Lord require of you, to love mercy, to act justly and to walk humbly with your God?”

Julius Achon’s father is a deacon, but he rotates between churches of every denomination when he returns to Otuke.

Initially, the foundation’s aim was to find sponsors for orphans, “to take the pressure off Julius”.

However, Wellings realised that children who still had families were suffering, too. When Achon told her about the famine deaths in his area, her foundation decided to start a food program.

“So that was the idea behind Cents for Seeds,” she says. “We give a loan, we stand alongside them, but the hard work is up to them. The idea is to bring people dignity and education.”

Cents for Seeds, which this year was a finalist in the Telstra Business Awards, provides local women with loans of 30kg of seeds for them to plant, usually yielding a harvest of about 150kg to 300kg of food.

Achon has seen a dramatic difference through this project around his own village of Awake over the past six years. During the Ugandan civil war, he explains, people fled the area for 21 years. The rebels burnt their huts and killed their livestock.

The fields lay bare in this normally rich agricultural area, cradled within a tropical rain fault belt, where rice, beans, peanuts, green peas, sweet potatoes, sesame and sunflower normally thrive.

“There was nothing,” Achon says. “No hospital. No schools. No homes. Just starting everything from scratch…

“In 2009, people were dying of famine. In my village, we lost 11 people through nothing to eat, and the condition was terrible. People had just gone back from their refugee camp after the war.

“They had nothing to eat, nothing to feed them and nothing to grow as a crop because in Uganda, the majority – 65 per cent – are farmers. In my village, almost everybody are farmers.”

Year by year, the fields have greened again and families have been able to afford to buy livestock and send their children to school. Climate change thwarted the first crop of the season with unseasonal drought this year, but a second crop shows better promise, Achon says.

Meanwhile, the foundation has raised the number of women it sponsors from 2000 to 7000 this year – with a goal of 20,000 by 2020.

On his first day back in Sydney this year, not long after Eloise Wellings has checked him for signs of life, Achon arises, eager for the eggs she cooks him.

That night, the pair co-star, telling their life stories at a glam $1200-a-head charity fund-raising dinner at Star City Casino for 20 donors, including Cronulla Sharks chairman Damian Keogh.

In the few days they have together, Achon offers advice which Wellings says will help her deal with the mighty force of her African competitors.

“He gives me tips on form,” she says. “Especially in the closing stages of the race, you notice that the Africans remain just as relaxed as they were at the beginning of the race. So they focus a lot on form and drills to be able to do that.

“He showed me some of those drills and just mental cues to maintain that relaxed stride, but also trying to pick up the pace.”

Achon explains it this way: “I… tell her, forget about everything. For me, I would assume the rebels were chasing me and I had to run and they could not touch me. So just assume that you’re in Africa and you’re being chased by rebels.”

Achon is still in awe of what running has done for him. “It’s brought amazing things, even up to now, 25 years since I began. I haven’t stopped running. I’m not stressful. I run for freedom and to have people’s life survive… I’m raising funds for the charity, so I enjoy it.

“Now I’m nearly 40 years old. Most of my friends retired 10 or 15 years ago. They’re not running no more.”

A few days later, Wellings leaves to train with the Australian athletics team in California and then Florida.

Achon strides out with local runners’ clubs in Sydney’s Centennial Park, Sutherland, and the Royal National Park. To him, the stress of living in a big city gets in the way of running well.

“You’re already tired by the time the race begins,” he says.

But Sydney has done him good. As the salt wind whips along a mall in Cronulla, he catches his reflection in shop windows and exclaims: “Cheekbones!”

The demands of political life and communicating with the world via computer have made him more sedentary than he was as an international athlete. Wellings has helped to bring those cheekbones back, as she has chivvied him to run and work out in the gym.

“If you want to succeed in life, you have to be a giver.... Many people will love you.”

In Sydney, Achon avidly follows world events, especially those in the US, where he has an African perspective on the president. There is a kinship. Barack Obama’s relatives in Kenya speak the same dialect as Achon’s family.

As Obama bows out, Achon begins his career. During his first speech in parliament, a week before catching his flight, Achon explained as part of a corruption debate why he did not support a proposal by MPs to raise their own salaries.

“I said, ‘If you want to succeed in life, you have to be a giver, somebody who loves the community, who shares with them. And more will come and many people will love you.’

“Like, with me, I am loved and Western world people support me, because I show my love to people by caring.”

Bit by bit, the village of Awake is receiving a small part of the bounty taken for granted in the West. Until nine years ago, Achon and his father would climb a mango tree to get good mobile phone reception. Nowadays, it’s in the village.

“We have an ambulance which is servicing the entire region,” he says. “Going 24 hours. In an hour, you find like, seven calls, but it can only go for the first one.”

Achon’s next quest is to raise the money to drill boreholes at $5000 each, so his district’s 260 villages can have decent water.

“People share the same well with the animals,” he says. “There’s no clean water. It makes people sick with typhoid, or waterborne disease.”

In November, as usual, Wellings will visit Awake to see what her foundation has done and to go on a fun run with the locals.

But right now, she’s in the final fortnight of her campaign to beat the Africans at Rio.

The plan, she explains, is to “sharpen up a bit with some speed work, and then it will just be about tapering really well”.

At least one African will be cheering for her.

Photos of Julius Achon by Tim Bauer.