The run-up to India's general election - scheduled in seven phases between 11 April and 19 May - has spawned a host of phrases and expressions in the media and politics of the country.

The terms reflect not just the vocabulary of this particular election, but also deeper themes in Indian politics that underpin the campaign rhetoric.

Religious identity, the issue of what constitutes patriotism, the role of the media, national security, electoral alliances, accusations of dynastic politics, corruption, and the economy are among them.

BBC Monitoring profiles some of the catchphrases and buzzwords in India's polarised discourse as the world's largest election are underway.

'Chowkidar'

A Hindi word which means "watchman", the term has often been used by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who calls himself the country's "chowkidar" to emphasise his eternal vigilance against corruption.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has now drafted Modi's use of the term into its election rhetoric, with many senior figures in the party – such as BJP chief Amit Shah, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, Human Resource Development Minister Prakash Javadekar and Modi himself – adding the word "Chowkidar" as a prefix to their names on Twitter.

BJP supporters have been promoting the Twitter hashtag "MainBhiChowkidar" - meaning "I'm also a watchman" - and the party has released a "MainBhiChowkidar" caller tune for mobile phones.

But supporters of the main opposition Congress party, which has often attacked Modi's claims of corruption-free governance, are promoting their own catchphrase, including on Twitter: "ChowkidarChorHai", which means "The watchman is the crook".

'Ram temple'

(Hindi: Ram Mandir): A proposed temple to the Hindu deity Ram at the disputed site of the destroyed Babri mosque in the northern city of Ayodhya, as demanded by Hindu nationalist groups.

According to the groups, the mosque was built after razing an ancient Hindu temple which stood there, as ordered by Muslim emperor Babur in 1528-29, and they seek to reclaim the area as a Hindu holy site.

A Hindu nationalist mob, including members of the now-ruling BJP, demolished the mosque in 1992, and the party promised to build the temple if it came to power.

But having formed the government in 2014, the BJP's term is now ending and the temple is yet to be built, leading some Hindu nationalists to accuse Prime Minister Narendra Modi of betraying their community.

Muslim groups also seek ownership of the site, and the dispute - which has sparked much intercommunal conflict over the years - is being heard by the Supreme Court of India.

'Cow vigilantes'

(Hindi: Gau rakshak, which literally translates to "cow protectors"): Vigilante squads that have engaged in frequent violence - often against Muslims and Dalits, the latter being members of underprivileged castes - in the name of protecting cows from being killed for beef.

Many Hindus consider the cow a sacred animal and don't eat beef, and cow slaughter is illegal in several states.

The issue came to prominence in 2015 when a 50-year-old Muslim man was killed by a Hindu mob in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh over rumours that he and his family had eaten beef.

According to the fact-checking website IndiaSpend, 125 incidents of violence have been reported from various parts of the country since 2012, mostly targeting Muslims, accused of smuggling cows or eating beef.

On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court directed all states to stop violence in the name of cow protection.

But opposition parties accuse the BJP government of not doing enough to rein in the vigilante squads, allegedly out of fear of alienating conservative Hindus who form its core voting base.

'Anti-nationals'

A loaded term suggestive of traitorous intentions, the word is sweepingly used by the government's supporters - such as ABVP in the picture above - for a variety of left-liberal critics: journalists, activists, writers, students, media outlets and - in one case - an entire university.

The term is a particular favourite of Hindu nationalists, who target critics of the ruling party's ideology and tell them to 'Go To Pakistan', India's arch-rival in South Asia.

This was particularly so in the aftermath of a militant attack at Pulwama in Kashmir on 14 February, which left over 40 Indian troops dead and was claimed by the Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad, who had recruited a local youth for the purpose.

The hashtag "DeshDrohi Patrakar" - Hindi for "anti-national journalists" - trended on Twitter after prominent journalists such as Barkha Dutt, Rajdeep Sardesai and Sagarika Ghosh voiced support for Kashmiris facing a backlash across India.

A close cousin of the term "anti-national" is the expression "urban naxal", which refers to intellectuals, activists or other influencers who, according to their critics, aim to undermine the Indian state. The filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri has used the term for those whom he calls the "invisible enemies" of the country.

But "anti-nationals" and "urban naxals" often quarrel with "bhakts" (see the next entry), and the emotion-laden words reflect the polarised nature of Indian politics.

'Bhakt'

A Hindi word which means "devotee", the term is meant as an insulting description of diehard supporters of Modi (seen in the poster at the centre of the image above) and is usually left untranslated by English-language media.

Bhakts are those who zealously celebrate Modi's successes or relentlessly defend his most controversial decisions – on the internet and elsewhere.

They have often been criticised for targeting the prime minister's critics online, shutting down conversations with insulting and threatening language, at which point they become trolls. Many say it is futile to debate with them.

The Indian author Chetan Bhagat wrote in 2017 that bhakts could be damaging for Indian democracy.

But Agnihotri disagrees, saying the bhakts "call a spade a spade" and hold journalists accountable for their biases.

'Acche Din'

A key Hindi slogan in the BJP's 2014 poll campaign which means "The Good Days".

It has re-emerged ahead of the 2019 election with an ironic twist, as the term is now being used by opposition parties to mock the BJP and Modi.

In 2014, Modi promised a better India, telling voters that "the good days" would arrive soon if he came to power. Among the pledges, his party made were a fight against corruption, the creation of a "New India" by 2022, more jobs and a doubling of farmers' income.

But the same slogan is now being used against the BJP by opposition parties who cite rising unemployment, cases of lynching, farmers' suicides and other issues to assert that Modi's promised "good days" never arrived.

'Demonetisation'

Modi's sudden announcement on 8 November 2016 that high-value currency notes were being withdrawn from circulation.

The government said this was aimed at curbing corruption, reducing the hoarding of undeclared cash to evade taxes, and preventing the funding of illegal activity and militancy.

But the decision led to prolonged cash shortages, rising unemployment, and disruptions to the farming sector and rural economy, among other problems - leading to widespread criticism.

Despite this, the government's supporters continued to applaud the move, maintaining that some trouble was worthwhile if it ensured the greater good of fighting the problem of undeclared cash hoards - called "black money" in the media.

And so, there was particularly strong criticism in August 2018, when India's central bank said that approximately 99.3 per cent of the demonetised banknotes had been deposited back into the banking system as the public sought to replace them for new tender - raising questions over whether demonetisation had succeeded in stemming the problem of black money.

'GST'

The three-letter abbreviation that humbly expands to "Goods and Services Tax" evokes fierce emotions and is a key weapon in the armoury of the opposition ahead of the election.

On 1 July 2017, the Modi government implemented a new tax structure that replaced multiple levies on goods and services at the federal and state levels.

Though praised by analysts as a key economic reform which would simplify an extremely complicated tax structure, its implementation was widely criticised.

Small businesses were the hardest-hit. Critics said the new law didn't give time for small business to adapt to the new mechanism.

Opposition parties have since attempted to capitalise on post-GST discontent and the issue is likely to be revived as the election draws closer.

'Grand alliance'

(Hindi: mahagathbandhan): A coalition of regional opposition parties who aim to contest as a united federal force against the BJP in the forthcoming elections.

The alliance was proposed in March 2018 and representatives of over 15 regional parties, including the chief ministers of several states, held a rally on 19 January 2019 in the eastern city of Kolkata towards attracting more parties into the fold.

The BJP has dismissed the opposition alliance as "comical" and "opportunistic", saying its only unifying factor is a hatred for Modi.

Such multi-party alliances are not new to Indian politics: the current BJP-led ruling National Democratic Alliance constitutes over 30 parties, whereas the previous ruling coalition, the Congress party-led United Progressive Alliance, had over 20.

'Dynastic politics'

(Hindi: vanshwad ki rajniti): The expression is one of the main criticisms used by the BJP - particularly Modi - against the Congress party and its chief Rahul Gandhi.

The BJP says the Congress party's functioning resembles that of a dynasty and therefore doesn't fit India's democratic ethos.

Rahul's great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru, grandmother Indira Gandhi and father Rajiv Gandhi served as the first, third and sixth prime ministers of the country.

His mother Sonia Gandhi was the Congress party's president for two decades before he took over in December 2017.

His younger sister Priyanka Gandhi also formally joined the party earlier this year, giving the BJP another opportunity to revive the "dynastic politics" argument against the Congress.

But Rahul has said that dynastic politics "is how India works" and that in any case, a person's background doesn't determine his capabilities.

'Brother-in-law'

(Hindi: jijaji): A term used by Modi and the BJP to lampoon Robert Vadra, Priyanka Gandhi's husband, whom they hold up as an instance of the Congress party's alleged nepotism and corruption.

The term 'jijaji' was in wide use ahead of the 2014 election but then fell out of the political vocabulary.

But it is now staging a comeback in Modi's speeches, along with 'damad', which means "son-in-law" and doubly underlines Vadra's ties by marriage to the Gandhi family.

The BJP accuses Vadra of wrongdoing in his real estate business in the states of Haryana and Rajasthan, and he is currently under investigation.

He and the Gandhis deny the allegations and have accused the BJP of a "political witch hunt".

'Surgical strike'

A term referring to two reported incidents - an Indian Army operation in Pakistan-administered Kashmir on 29 September 2016, and an Indian Air Force (IAF) bombing operation in Pakistan on 26 February 2019.

Both came after militant attacks against troops in Indian-administered Kashmir - the first at Uri district on 18 September 2016 which left at least 20 soldiers dead, and the second at Pulwama district on 14 February, in which at least 40 soldiers died.

On both occasions, India subsequently said it had successfully attacked militant locations by means of surgical strikes, but in the first case, Pakistan denied there was any such operation in territory it controls, and in the second case said the IAF entered its airspace but did not succeed in hitting any targets.

The terms Uri, Pulwama, "surgical strike" - and even "surgical strike 2.0" for the reported IAF operation - have subsequently become part of the Indian media vocabulary.

The government has also promoted the term "surgical strike" to push a narrative about its decisiveness on the issue of terrorism, and its supporters have criticised those who question the term, calling them "anti-national".

'Rafale deal'

A multibillion-dollar deal to buy French fighter jets which have sparked controversy as the opposition Congress party accuses the BJP-led government of corruption - which the government denies.

It involves a plan to buy 36 "ready-to-fly" Rafale fighters from aircraft-maker Dassault Aviation for around 8.7bn dollars, as agreed between the BJP government and French authorities in 2016 - and replaces a plan from 2012, when the Congress was in power, to buy 126 aircraft.

As part of the deal, Dassault will reinvest 50 per cent of its proceeds to manufacture some components of the jet with Indian businessman Anil Ambani's firm Reliance Defence Limited.

The Congress says the BJP's deal involves paying more for each aircraft and that it favours Reliance Defence, which the Congress says was "unfairly" recommended by the government to become Dassault's Indian partner.

But the government says its deal ensures a better price and faster delivery of the jets, while Reliance Defence denies it was unfairly chosen and Dassault says it is committed to delivering the jets.

India's Supreme Court has dismissed demands for a federal probe into the deal, and a report from India's state auditor - the Comptroller and Auditor General - says the overall price of the jets is 2.86 per cent less than in the deal negotiated by the previous Congress-led government.

However, Congress is not backing down and continues to play up the issue.

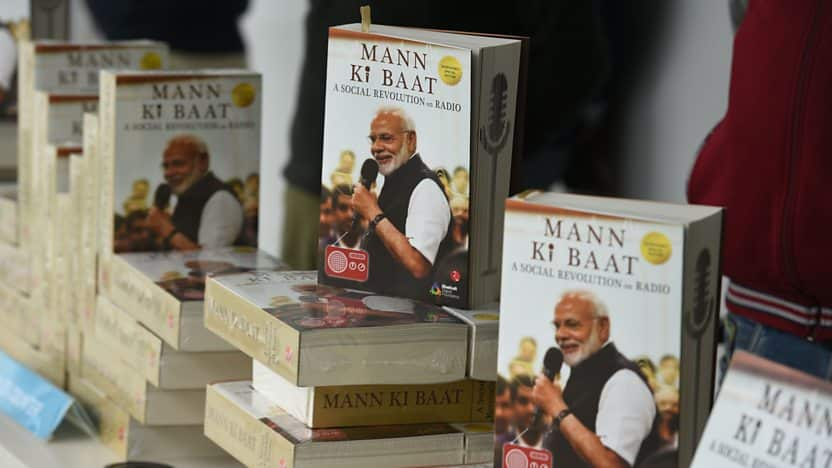

'Mann Ki Baat'

Meaning "From the heart", the Hindi phrase is the title of a series of monthly radio talks from Modi, where he speaks on his government's accomplishments and gives advice on dealing with problems such as exam stress, climate change and drug addiction.

The series has drawn criticism from political rivals, with the Nationalist Congress Party - not to be confused with the Congress party - saying in 2016 that the programme should be cancelled as people have "lost faith" in Modi's promises.

But Modi's supporters such as Jaitley have said that speaking over the radio is "far more effective" than answering questions from reporters - Modi has never held a press conference as prime minister.

Meanwhile, as the election approaches, Modi has suspended the series in March and April and said it will resume in May after the poll results are declared.

Source: https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk/