Pakistan sits at the intersection of some of the world’s great cuisines. Thanks to shared borders with Afghanistan, China, India, and Iran – and a history of migration and trade – Pakistani dishes draw upon a marvellous array of flavours and ingredients.

In the northwest, the rugged borders between Afghanistan and Pakistan blur. Pashtun tribes such as the Shinwari, which exist on both sides of the border, share a rich culinary tradition of salted lamb prepared either skewered on a flaming charcoal grill or fried in a massive blackened wok over a tomato base.

On the coast, historical fishing communities haul nets of crab, prawn, and dozens of varieties of fish that are grilled, fried, or folded into richly spiced curries.

Visit Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city, and you will find a succulent nihari, dressed with heaps of ginger, or countless variations of biryani, each telling the story of a different migrant community that makes up the city’s twenty million inhabitants.

Bhapu is a favourite dish of fishing communities on the coast of Sindh, in southern Pakistan. Get the recipe from Maryam Jillani's book here.

On the table, if you are lucky enough to be invited to a Pakistani home for a dawat (which directly translates to feast), you will be spoiled for choice. Pakistani hosting rules dictate that the spread include a meticulously prepared rice dish, a meat curry, some version of kebab or cutlet, a side of vegetables, a relish or chutney, and, of course, sliced fruit and tea. Expect to be stuffed silly in the first round and still be pressed for seconds and thirds by your hosts.

Step into a bazaar, and you will be taken in by the astonishing variety of consumables, from dried fruits like figs and apricots that Pakistanis snack on all winter long to heaps of spices – coriander, cumin, mint, saffron, and turmeric – that have come to define South Asian cuisine.

These are but a handful of scenes that comprise the colour and beauty of Pakistani food. But despite the incredible flavours and respectable size of the Pakistani diaspora (estimated at about nine million across the world), Pakistani cuisine continues to lack visibility. One reason is that it continues to be conflated with Indian food.

Maryam Jillani often serves bhindi masala as a side to a curry. Get her recipe here.

In many countries, there is often the false assumption that Pakistani food only exists in relation to Indian cuisine. In reality, it is determined by its regions and communities. There is, of course, overlap due to the countries’ shared history, but the overemphasis on their similarities comes at the expense of food from provinces and territories such as Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or Gilgit-Baltistan, none of which share a border with India.

It also undermines how the cuisine has considerably evolved since Partition, with settled communities absorbing the culinary influence of migrants, including those migrant communities less talked about in Pakistan, such as those from South Indian states. And with the long-standing presence and influence of Afghan refugees, popular Afghan classics, such as kabuli pulao and borani banjan too are now a part of Pakistani food.

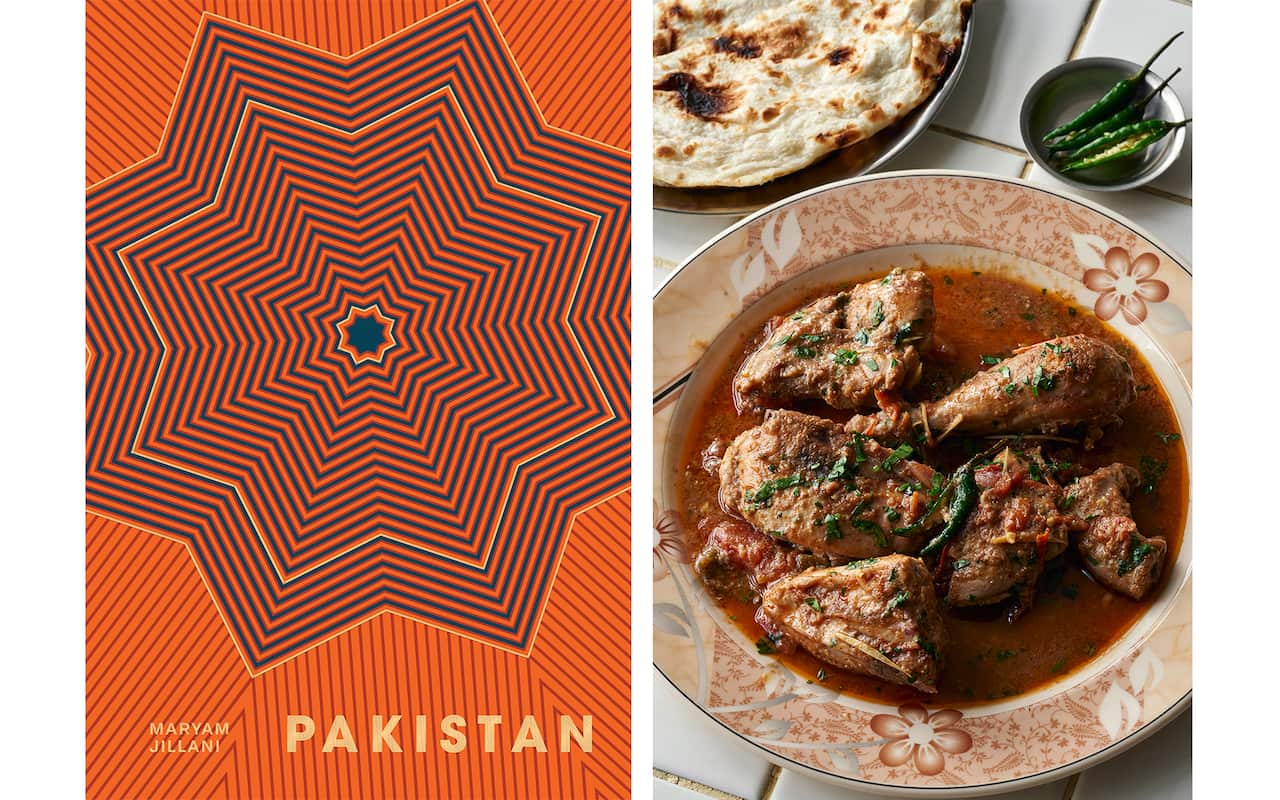

But if Pakistan had a national dish, it would probably be chicken karahi.

This forward-leaning view of what constitutes “Pakistani food” also considers the impact of economic liberalisation during the 1990s. I grew up in Pakistan at a time when globalisation was ramping up, and saw Pakistani groceries, restaurants and home kitchens becoming international. There was a slow buildup of steady demand for desserts like coffee cake and Black Forest cake – now regular fixtures in Pakistani bakeries.

At home, in addition to the regular rotation of dal chawal (lentils and rice), chicken ka salan (chicken curry) and aloo gosht (mutton with potatoes), my mother would also make a mean keema spaghetti – South Asia’s take on bolognese, in which overcooked spaghetti is paired with a Pakistani-style ground beef and a generous helping of ketchup.

Today, Pakistani cuisine is colourful, global and breaks the rules.

Eating the Pakistani way

While there are no hard-and-fast rules to putting together a Pakistani meal, the general norm is to try to maintain a balance between consistency and flavour. Rice is normally served alongside dishes with gravy, while many prefer to have drier dishes (especially meats) with roti or naan. The milder your main, the more sharp and spicy your chutney or pickle. Meat is typically the star of the table, but there will nearly always be a vegetable side.

That said, rules are meant to be broken, so play around to see what you like. We typically close a meal with fruit and tea, and reserve desserts for guests and special occasions.

This is an edited extract from Pakistan: Recipes and Stories from Home Kitchens, Restaurants, and Roadside Stands by Maryam Jillani (Hardie Grant Books, HB $55). Photography by Sanjeev Thakur, Waleed Anwar and Insiya Syed.

SBS Food is a 24/7 foodie channel for all Australians, with a focus on simple, authentic and everyday food inspiration from cultures everywhere. NSW stream only. Read more about SBS Food

Have a story or comment? Contact Us