When most people picture Singapore’s dining scene, they imagine glossy plates and Insta-perfect hawker heroes with Michelin stars. But in the lanes of Geylang, beneath the city’s polished façade, there’s another story simmering, one that smells of garlic, wok hei (literally “the breath of the wok”), and a city still awake long after midnight.

It’s 6.30 p.m. when I meet my guide, Wei, outside Aljunied MRT. The air hangs heavy with humidity and promise. “Ready for something real?” he grins, and leads me to our first refreshment close by, 8890 Eating House, a typical no-frills kopitiam where metal spoons clatter and I’m handed a plastic bag of yuan yang, a half-coffee, half-milk-tea hybrid that perfectly represents Singapore’s instinct for fusion. I sip, unsure at first, then grin. It tastes exactly as it sounds: half jittery caffeine, half milky nostalgia, a liquid collab between east and west and was believed to have originated in Hong Kong after WWII.

We set off into the night. The streets hum with scooters, sizzling woks, and the faint sweetness of durian wafting from a nearby stall. As we walk, Wei gestures to the old shophouses glowing under fluorescent tubes. Each has its own story, food, family, sometimes vice. All of it makes Geylang what it is.

This is where Singapore’s contradictions live comfortably side by side. Families tuck into supper as shift workers clock off. New condos rise beside century-old clan buildings. Even Geylang’s red-light district, a regulated, medically monitored system the state quietly maintains to preserve public order, sits here, discreet but undeniable, adding another layer to the neighbourhood’s pulse.

People think of Geylang as one thing, but really, it’s everything.Wei

From there, the night deepens. Wei leads me through narrow streets and main roads that bloom into light as the stalls fire up. We stop at a hole-in-the-wall bar called Skewers, where he orders something “sweet and smoky.” When it arrives, I bite into what I think is bacon until the texture changes mid-chew. It’s soft, almost floral. “Bacon-wrapped lychee,” Wei laughs. “Ugly but addictive.”

That phrase, ugly but addictive, could sum up his entire philosophy. Wei co-founded Indie Singapore, a local tour outfit dedicated to telling the “real” Singaporean food story, one that refuses to airbrush the grit from the plate.

“I was watching the world fall in love with the polished version of our cuisine,” he says. “The fine dining, the celebrity chefs, the Insta bites. But our true flavour, the one that built this city, lives in the messy, brown, delicious stuff that doesn’t photograph well.”

He’s talking about dishes like kway chap (braised pork offal with rice sheets) or bak kut teh, that peppery pork-rib soup eaten for breakfast, hangover or not. Food born from thrift and necessity and cooked by hands that remember hardship and hunger.

As we walk, Wei points to a building with ornate wooden doors, one of Geylang’s many clan associations. His own family’s clan is nearby. “Long before the government provided welfare,” he explains, “these associations were the safety net. They housed new migrants, taught language, arranged jobs. And they still matter today, they’re where people gather for festivals, banquets, even matchmaking!”

Inside, the smell of incense lingers, and on the walls, ancestral tiles look down on us like keepers of memory. “You see?” Wei says softly. “Even our food comes from this idea of looking after one another. That’s the Singapore spirit, eat together, survive together.”

We move past neon signs advertising frog porridge and durian buffets. Wei chuckles at my face as we pass a mountain of spiky green fruit. “Durian divides families,” he jokes. “Some say it smells like heaven, others like sewage.” I snap photos of the creamy, custard-like, and alarmingly pungent fruit. I can’t bring myself to eat it today, having had the pleasure before.

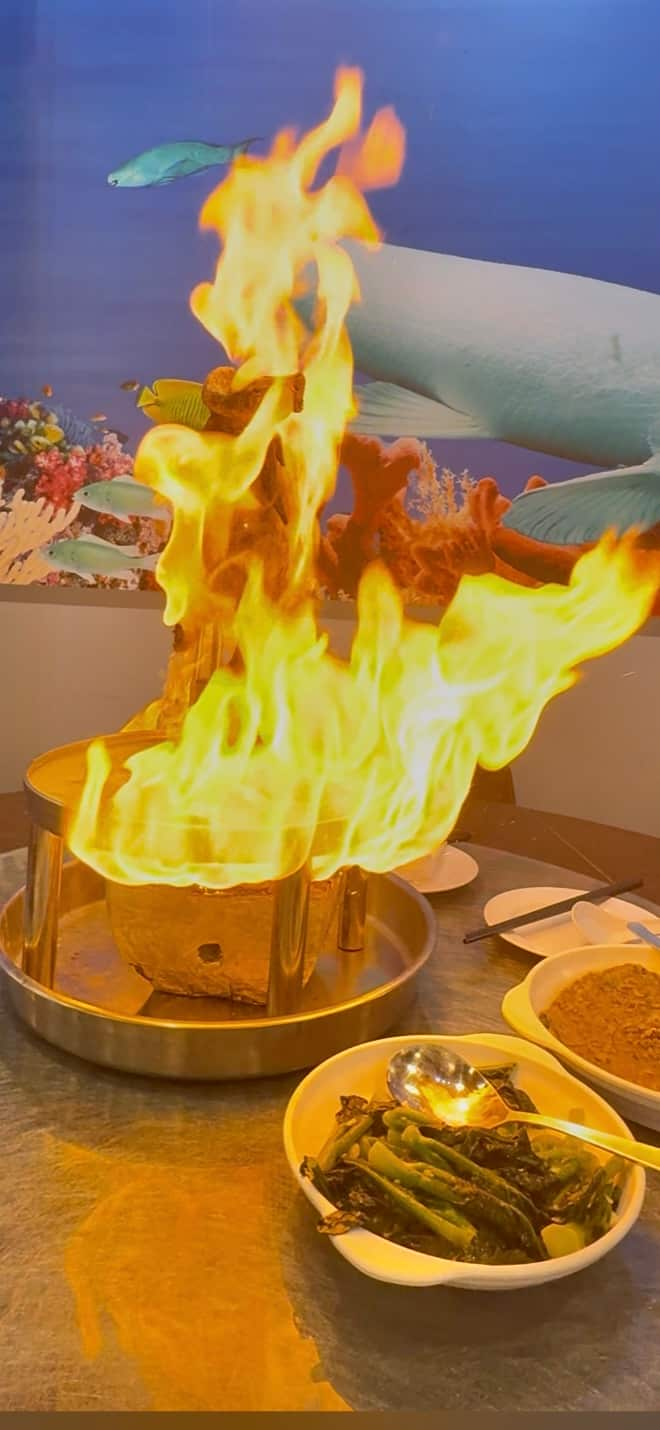

By 8.30 p.m. we reached Happy Seafood Village, our final stop. The tables are crowded with locals sharing Tiger beers, voices raised over clinking shells. Here, the famed volcano chicken arrives like a performance. A whole bird, doused with liquor, and set alight. Flames lick upward before being snuffed out, revealing golden, blistered skin and a scent that has my mouth watering.

We pair it with chao ta beehoon, the humble rice vermicelli fried until crisp and smoky, then topped with prawns and squid. The burnt edges are the point, they hold the story of fire, patience, and a hawker’s lifetime of muscle memory.

As we eat, Wei reflects on how Singaporeans are rediscovering these humble foods. “Younger people grew up with avocado toast and bubble tea,” he says. “But now they’re coming back to hawker food. They’re proud again. They know these dishes carry their grandparents’ stories.”

That nostalgia, he believes, is Singapore’s secret ingredient, the invisible spice that binds the city together. “Food here isn’t just about taste,” he adds. “It’s our love language. It’s how we talk about home, even when we can’t find the words.”

The tour ends the way the night began, with a drink and a moment of quiet. Around us, Geylang thrums with the unpolished rhythm of a city still eating, still living. Old men share beer towers, teens scroll TikTok between bites, aunties ladle soup like it’s medicine for the soul.

As we walk out I realise how different this Singapore feels from the brochure version, rawer, louder, more alive. It’s a place where beauty hides in imperfection, where the truest taste might come from a chipped bowl and a stranger’s smile.

I leave with a full belly, a head buzzing from too much yuan yang, and a sense of having glimpsed something honest. Beyond the pretty plates, Geylang’s supper tables hold a heartbeat all their own, one that hums with memory, migration, and the universal comfort of a good meal shared under fluorescent light.

SBS Food is a 24/7 foodie channel for all Australians, with a focus on simple, authentic and everyday food inspiration from cultures everywhere. NSW stream only. Read more about SBS Food

Have a story or comment? Contact Us