“Can I please use some language examples? I like to give a taste of the language.”

Brother John Giacon is always keen to show what Gamilaraay sounds like.

“'Yaama', hello, and 'Yaluu', goodbye, are two basic words that it’s always good to know,” says the Christian Brother who has spent decades working on the reinvigoration of Australia's Indigenous languages.

Two years ago, based on his work at ANU, he was the recipient of the Patji-Dawes Award, Australia's most prestigious recognition for language teaching.

Born in Italy and raised in Australia since he was four, Brother Giacon first got involved with Yuwaalaraay language in the '90s, after moving to Walgett, a small town in rural central-North New South Wales. Soon after he began working with Gamilaraay, a very similar language.

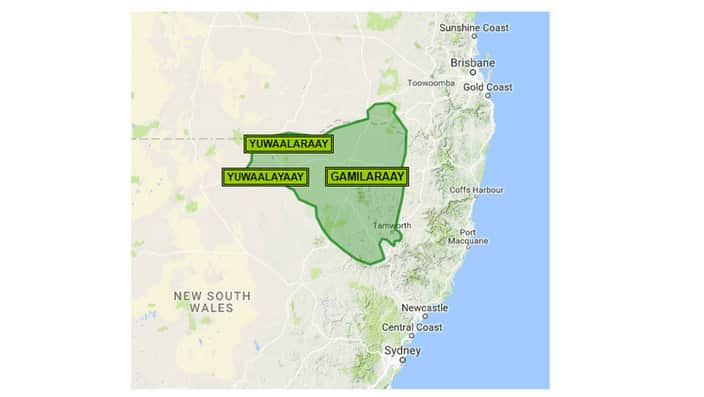

Gamilaraay (also known as Kamilaroi or Gomeroi), is an Indigenous language originating in Gamilaraay country, an approximate 400 square kilometre zone across New South Wales and Queensland. For reference, Walgett sits near the far west edge of this Gamilaraay country, while Armidale sits on the Eastern side.

According to the 2016 Census, Gamilaraay speakers in Australia are no more than 100 individuals. Giacon is surprised when presented with this number.

“I have never met anyone who could speak it at a good level without attending classes," he tells SBS Italian, “Lots of people know words, but not the grammar.”

The grammar of Gamilaraay is, unsurprisingly, a crucial part of Giacon's endeavor to awaken this sleeping language. Europeans first recorded the language in the 19th century, and their work provides one source from which Giacon works.

“A little of the grammar [of the language] was written in 1850 and tapes recorded around 1970. We worked with these sources and wrote down the language’s grammatical rules once again.”

“Now we have a dictionary and a modern grammar book,” he says with pride.

Unexpected connections

How though, an Italian-Australian man can master the pronunciation of a culturally distant language?

John has spent thousands of hours listening to tapes to learn proper pronunciation, but says, “the truth is the new Gamilaraay will have a different pronunciation compared to the traditional one, like a person who speaks English with an Italian, German or Japanese accent.”

Accent is not an issue, according to him, as effort must be directed to awakening the language, and he is confident it can be restored.

“In the recent past we have seen politicians using Aboriginal languages in Parliament and I think that New Zealand, where Maori language is widespread, is the example to follow”.

Gamilaraay is a language Indigenous academics describe as 'sleeping', a gentler term than the common English of 'endangered', or even 'dead'.

Giacon says the challenge of reinvigorating the language is huge since “nobody is able to have a fluent conversation in Gamilaraay."

For Gamilaraay speakers, reconnecting with the language is a journey itself.

“I knew more words than I remembered later on growing up,” says Billy Williams, a Gamilaraay man who wants to learn the language and pass it to his kids. “We had lots of distinct words, but we never ever spoke them in conversation.”

Many Gamilaraay words haven’t been recorded and other modern terms have not yet been created due to the length of time for which the language has been dormant. Writing in Gamilaraay is also tricky, as for many languages hailing from Indigenous Australia's predominantly oral cultures.

“There were lots of different writing systems, and the first academics who studied the language didn’t have lots of experience in Aboriginal languages,” explains Giacon.

The legacy of colonisation

Grammar, pronunciation and writing systems are not the only obstacles to the language's return.

In the Gamilaraay area, the population was heavily affected by the British invasion. The vast majority of Gamilaraay speakers died from starvation, diseases such as smallpox and acts of violence, and in the past many were punished for speaking Gamilaraay publicly.

“I personally met a few people in Walgett who told me they were disciplined for using their mother tongue. And sometimes the police got involved,” says Giacon.

“Up until the '60s, if a white parent complained [about them speaking the language], an Aboriginal kid could have been expelled from school.”

As the decline of Gamilaraay is directly connected to European, mostly Christian colonisation, Brother Giacon does sometimes find himself in a difficult situation as an Italian- Australian teaching the language.

“Once after recess an Aboriginal student didn’t return to class. When I asked him why, he replied that he spent all of his life resenting white men because they took away his language and couldn’t stand the idea of being taught by one of them.”

“I can understand there are people like that,” says Giacon's student Billy Williams. “For me, I’m very grateful to John’s work.

"I can understand some of our people are confused or angry. For me it’s 100 per cent the other way. The reactions vary across the spectrum. Some people really happy, some thinking, ‘oh yeah whatever,’ and some are really upset."

Language as a political statement?

Giacon says the main drive for learning and speaking Gamilaraay is “emotional”, drawing a comparison to his daily use of Italian words like 'ciao' and 'caffelatte'. Even a sparse sprinkling of non-English words helps him to remember his heritage and show others that he is proud to be Italian, and he believes the same happens for Gamilaraay people.

“When you utter even just few words of Gamilaraay, it becomes a political statement, and a powerful one. It’s like saying I am publicly affirming that I am Aboriginal or want to show respect for Aboriginal people.”

Giacon hopes that learning and speaking even small parts of Indigenous language could be used by the wider Australian community as a sign of respect.

“Language is all about your identity and your connections," says Billy Williams. "All of our old stories were in languages and to connect to this country and to our places we need our languages. It is hard, but if we don’t do it now, I am worried that the next generation will lose it forever.”