Father of four Rakan Abed El Rahman spends his days in Gaza searching for both food and news to share with the outside world.

"I struggle every day to feed my family, to survive this starvation in the Gaza Strip," he says.

The 37-year-old journalist is a regular contributor and camera operator who assists with SBS news-gathering in Gaza amid an ongoing ban on international media.

His day starts at the local market, where he says even the most basic foods are hard to find.

"I've spent hours in the market looking for any kind of food, simple food ... the situation here is really, really difficult, and people cannot find anything to eat.

"For days now, I have been looking for milk for my two-years-[old] baby and I haven't found it yet, which really, really breaks my heart that I'm not able to provide it."

What food can be found for his infant and other children — a 12-year-old daughter, and two sons aged eight and 11 — comes at a steep price.

"One kilo of this tomato is about maybe 15 US dollars."

Abed El Rahman is among the 2.1 million population of Gaza facing "the worst-case scenario of famine", according to UN-backed food security experts.

Two out of three famine thresholds have been reached in the strip, according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification platform.

'A grave risk of famine'

Officials from humanitarian groups like the UN Children’s Agency, UNICEF, say the region "faces a grave risk of famine".

Since Israeli attacks on Gaza in response to Hamas' attack on southern Israel on 7 October 2023, at least 100 people have died from malnutrition, according to UNICEF — 80 per cent of them children.

International aid organisations issued a litany of warnings of stocks running low after Israel cut off all supplies to the territory in March, then reopened it in May but with new restrictions.

Now, according to UNICEF, "severe malnutrition is spreading among children faster than aid can reach them" in Gaza, citing data from the Palestinian Ministry of Health.

At least 16 children under five have died from hunger-related causes since mid-July, while over 20,000 were treated in hospitals for acute malnutrition.

Israeli officials deny that starvation is occurring in Gaza.

"We don't recognise any famine or any starvation in the Gaza Strip," Israel's deputy chief of mission in its Canberra embassy, Amir Meron, told a group of reporters, including SBS News, on Monday.

Israeli officials have instead blamed either the United Nations' inefficiency or Hamas for aid not reaching people in areas it has claimed to control for much of the war, a claim that Hamas has denied.

According to internal UN databases, since 19 May 2025 over 1,750 aid trucks have been intercepted "either peacefully by hungry people or forcefully by armed actors, during transit in Gaza".

- DFAT meets with Israel's ambassador after statements denying starvation in Gaza

- Albanese says Israel 'clearly' in breach of international law amid starvation in Gaza

- Israel announces daily pauses in military bombardment of Gaza as aid airdrops begin

In response, Israel has installed the US-backed Gaza Health Foundation as the primary deliverer of aid in Gaza, which the UN had declined to work with, saying it distributes aid in ways that are inherently dangerous and violate humanitarian neutrality principles, contributing to the hunger crisis across the territory.

More than 100 people were killed, and hundreds of others injured, along food convoy routes and near Israeli-militarised distribution hubs in the last two days of July, according to the UN.

The GHF says nobody has been killed at its distribution points, and that it's doing a better job of protecting aid deliveries than the UN.

The Israeli military has acknowledged that civilians have been harmed by its gunfire near distribution centres, and says its forces have now received better instructions.

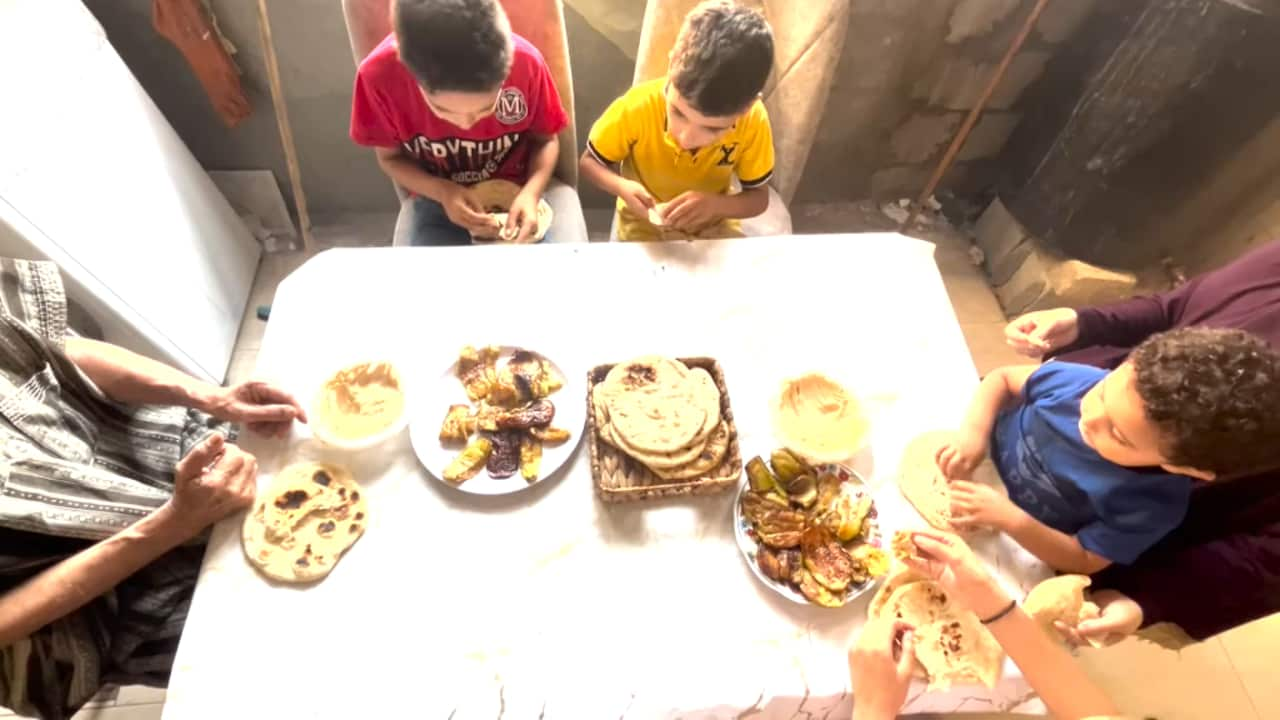

'This is my daily meal'

On the day of recording the video diary embedded above, Abed El Rahman found flour — something that isn't a regular occurrence, he says.

The portions of flour are taken from a bag clearly marked with the World Food Programme logo, which Abed El Rahman believes was stolen from aid deliveries.

He buys two kilograms of flour, a kilo and a half of eggplant and two plates of hummus.

Whatever he's able to find at the market makes up the one daily meal he and his family eat.

"This is my daily meal, it is just one meal, it costs me around 80 dollars," he says.

"This is a heavy burden on me … and it's a privilege for me that I can buy it now, some days I cannot buy it because I don't have the cash to buy this."

On those days, he says, the family goes to bed hungry. But he's grateful they still have a roof over their heads.

In the first month of the war, an Israeli airstrike destroyed his neighbour's home and partially destroyed the second level of his home where his father had been staying, he says.

"The rescue teams pulled out my father from under the rubble … lucky for me, me and my family were not here at home on that night."

Sometimes though, hunger makes it hard for him to leave the house.

"I am constantly dizzy, exhausted, [and] tired due to the lack of food. I approximately lost 15 kilograms in a short time. There are numerous days that I cannot go to work because of [a] lack of energy in my body."

At home, Abed El Rahman prepares the meal with his 11-year-old son, who gathered scrap wood to make the fire on which they will cook as gas is no longer available in the strip.

He's grateful that he's able to provide for his family — at least for today.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.