There's a lot of money to be made in Australia's 'ghost towns'.

Scattered along the country's coastlines and nature destinations are spots where the majority of homes sit empty for the bulk of the year, awaiting the return of their owners or short-term holidaymakers come summer.

Nationally, there were just over a million homes empty on Census night in 2021 — around 10 per cent, but less than the nearly 11 per cent at the previous Census in 2016.

But there are pockets of the country where that vacancy rate balloons — and alongside it, home values.

While it's difficult to know exactly how many of the unoccupied properties on that Census night were holiday homes, 10 August 2021 was a Tuesday evening in winter, and many of the county's getaway homes likely sat dormant.

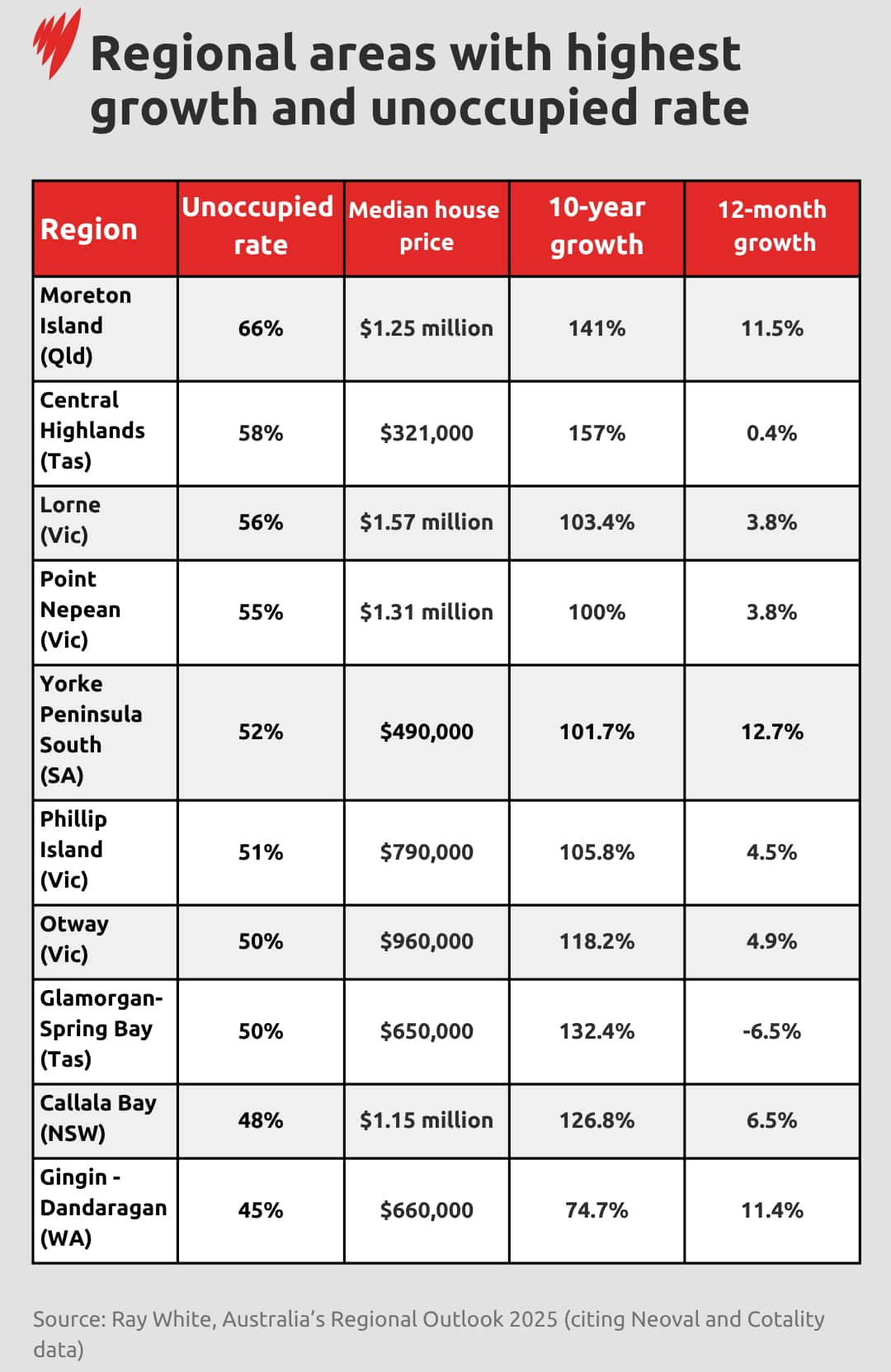

Recent analysis by real estate company Ray White identified 10 regional areas with high vacancy rates where home values have had "astronomical" growth in the past decade, "defying" the conventional logic that high vacancy rates reflect slow market growth.

Of the 10 areas it highlighted, the highest vacancy rate was in Moreton Island, off the coast of south-east Queensland, with a population of under 300 and a vacancy rate of 66 per cent.

The island has experienced 140 per cent growth in the median house price over the past decade, with the average home now sitting at $1.25 million.

But there are less extreme examples. The Central Highlands in Tasmania had a 58 per cent occupancy rate, with a 10-year growth of 157 per cent.

Both Point Nepean and the Lorne-Anglesea regions in Victoria had vacancy rates above 55 per cent, with a 10-year growth of 99.9 per cent and 103.4 per cent, respectively.

The average home in Point Nepean now sits at $1.31 million, while in the Lorne-Anglesea area that figure rises to $1.57 million.

On the NSW south coast, the 15km strip between Callala Bay and Currarong had a 48 per cent vacancy rate — but a 126.8 per cent 10-year growth rate, with the average home now at $1.15 million.

Vanessa Rader, Ray White's head of research, said the report revealed Australia’s holiday home phenomenon had a concentrated geography, and these areas challenged fundamental assumptions about property investment returns.

"Using unoccupied housing data as a proxy for holiday home concentration reveals regional markets operating under entirely different economic principles than metropolitan residential investment," Rader said.

Nicola Powell, Domain's chief of research and economics, agreed that the locations were united by their lifestyle and holiday home appeal.

'Classic' coastal or nature-based destinations had surged in recent years as Australians “increasingly sought lifestyle property”, particularly following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the move to remote and hybrid work, she said.

"I think it permanently boosted demand for homes in scenic and lower-density areas," Powell said. "When you look at these regions, they cater for both second holiday homes, but also short-term letting as well."

Powell said the scarcity of homes available to buy was also keeping property prices high in those areas.

"The limited stock and the high unoccupied proportion of dwellings really feed this," she said.

Given that surge, a holiday home can seem a straightforward investment for those wealthy enough to make one.

But looks — even pristine and coastal — can be deceiving.

What other considerations are there?

Rader warned holiday homes can come with "huge" holding costs before a buyer has even spent a summer in one.

"Highly unoccupied regions operate infrastructure designed for seasonal rather than permanent populations. Holiday home owners encounter service connection delays, limited provider options, and higher charges reflecting peak-period capacity constraints," she said.

Rader said recent regulatory changes designed to respond to affordability pressures in the housing market could also reduce rental income potential for holiday home investors — such as Victoria's 7.5 per cent levy on short-stay platforms and councils implementing rates surcharges for Airbnb properties.

In the case of a remote location like Moreton Island, she said building materials and tradespeople required ferry transport, significantly increasing maintenance costs.

But perhaps the most significant concern is that many areas with high vacancy rates experienced environmental risks beyond what most traditional residential investments faced — and thus, higher insurance premiums.

Ray White's report said properties in coastal areas could often attract insurance premiums 20 to 30 per cent above regional averages. Premiums for Moreton Island, for instance, often run 30 to 40 per cent above mainland alternatives, according to Ray White's analysis.

"[Premiums] have grown so considerably, and we are a nation that has a lot of these kinds of big natural disaster type events, unfortunately, particularly fires and flooding. It's really built into this kind of new cost to even own these properties," Rader said.

"In order to hold onto these assets, the outlay is far higher than they have been in the past."

Powell also said Domain's research indicated that Australians priced in considerations like bushfires and riverine flooding when buying a home, with the price impact rising as those risk factors increased.

However, she said coastal erosion — the loss of land along the shoreline due to factors such as rising sea levels — didn’t appear to have the same impact on price.

"What we found was that buyers prioritise location and views over those long-term risks. For every 10 metres away from the coast, the value of the home declined by 2.6 per cent," she said.

"We found that if a property is first in line [to the sea], it adds 20.4 per cent to the home's value, and if there's no road break, it adds another 5.4 per cent. So it really shows Australians prioritise lifestyle over risk."

Powell said that anyone looking to buy in one of those locations needed to be careful.

"If you're unsure of what the risk is associated with the home that you're looking at, the quickfire way to find out is to get an insurance quote. The premiums really do tell you the risk profile."

Is the bubble bursting?

Powell said there was "always going to be" an element of demand for homes in these prime holiday locations.

But it remains to be seen whether the price growth in these areas is sustainable. In the last year, Glamorgan to Spring Bay in Tasmania experienced a 6.5 per cent annual decrease, with a 0.4 per cent increase in Tasmania's Central Highlands.

While both Lorne-Anglesea and Point Nepean had high 10-year growth, they both had "modest" annual growth of 3.8 per cent. Rader says this suggests premium markets are reaching "natural appreciation limits as affordability constraints restrict buyer expansion".

With climate change continuing to intensify risks like rising sea levels and extended bushfire seasons, Rader said the long-term viability of homes in these scenic — but vulnerable — locations was also increasingly threatened.

Rader made the point, however, that even with a price ceiling, "if there is a beautiful, lovely, newly built home, [high] prices are still being achieved".

Does that high residential growth translate to commercial markets? It's unlikely, Rader said.

"Say you had a suburb with retail shops, if you can't keep your tenants in there because there isn't enough flow-through traffic, or they can only survive three months, six months of the year … not all businesses can do that," she said.

"How viable is that for that business? And then, how viable is that for the landlord that's trying to rent it out? So they're having to take a hit on their terms of their rent to make sure they keep the tenant in there."

If rising prices push people out of these areas, those locations will likely swing more and more towards being holiday tourism markets, cyclically driving increasingly higher vacancy rates.

"That market would really just cement itself as being a tourism destination first, more than a residential location. But people do need to live in these places, too," she said.

"If it were more of a trend and the prices were escalating so much, we would find local people would probably move slightly outside of that kind of core location," she added. "The prices in that location would continue to increase, and in turn, the occupancy rate would continue to fall as well."

Rader said that as values rose in what were otherwise quite regional locations, with limited infrastructure because the population couldn't support it, "there's only so much that you think that those markets can grow in a broader sense".

"People aren't there all the time. There's only so many shops that can be there or so many activities that can always be on, or gyms and things that people like to go to, hospitals as well," she said.

"If you want to go on holiday somewhere, you want to have that kind of holiday experience. But can that holiday experience really be there when half of the year there's no one actually living in these locations?”

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.