Sara and Paul Trotter's eldest son Riley is only 12, but he already acts and thinks like a competent farmer.

Riley's face lights up when talking about riding in the header or the truck with mum and dad, and he is knowledgeable about crop soils in Victoria's fertile Wimmera region, where his family lives. His enthusiasm is matched by his little brother Liam and sisters Sophie and Ella, who proudly attest that women can do anything men can do on the farm.

"We learned to do everything here, we've got a lot of freedom," Riley says.

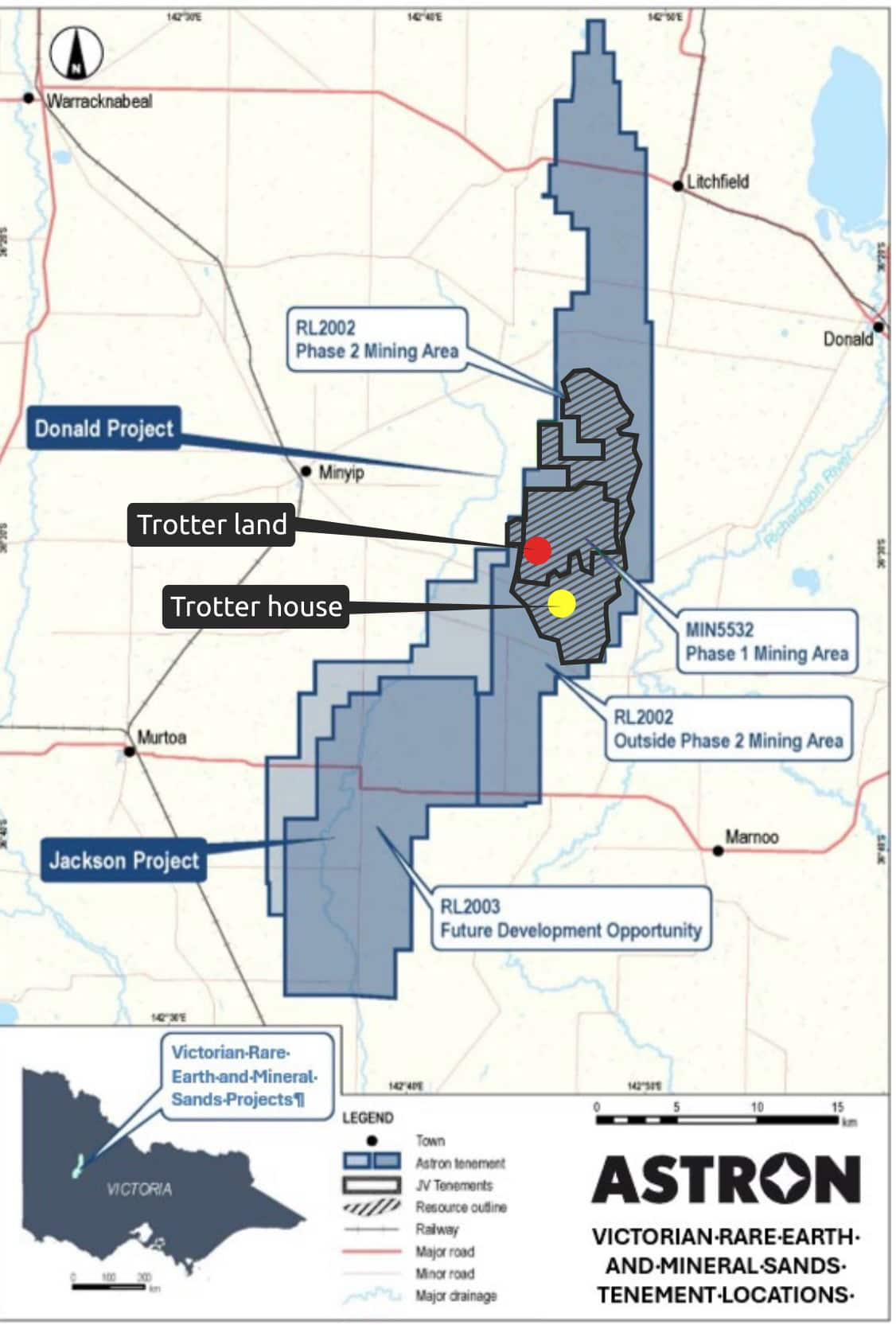

Since the early 1930s, the Trotter family has farmed near Minyip — a small rural town about 3.5 hours north-west of Melbourne — where Paul and Sarah's children were on track to become sixth-generation farmers.

But that plan has been blown apart by news the family received in late June that the Victorian government has approved a work plan for a mineral sands mine to operate on the Trotter family farm, with construction set to start as early as next year.

The implications for the family are profound.

The 'Donald Project' is a joint venture between the mineral sands mining and processing company Astron Limited and Uranium producer Energy Fuels, which will jointly operate the mine, trading as Donald Mineral Sands (DMS). Spanning 1,140 hectares, the mine is set to become Australia's second-largest rare earth project, the fourth-largest outside of China.

When the second phase comes into effect in the 2030s, the Trotters say they will be forced off their land. They won't be able to live in their newly renovated house and stand to lose 500 hectares of cropping paddocks.

The boundaries of the mine will extend to within 200m of their home, which planning documents indicate will be subject to noise and dust for 42 years, effectively making the house uninhabitable.

For Paul and Sarah, the approval of Astron's work plan was "gut-wrenching", and having to tell their children was "very upsetting".

"It feels exactly like the Castle — we're the little guy," Paul tells SBS News, referring to the classic 1997 Australian film.

It feels like you're banging your head against a brick wall.

In the film, a judge rules in favour of the Kerrigan family, who are fighting to save their home from demolition as part of an airport expansion.

But while the fictional judge cites Commonwealth law, requiring property to be acquired under "just terms", state and territory governments in Australia still retain powers to compulsorily acquire land under certain circumstances. In Victoria, the Mineral Resources Act also allows companies with a mining licence to acquire land if they can obtain written consent from the landholder or establish a compensation agreement. If an agreement can't be reached, either party can refer the matter to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Sarah says the family wasn't notified that the plan had been approved; they only found out when a local journalist called.

"This is our home," she says.

"My husband and I have worked exceptionally hard and we want to be able to enjoy it and we want our kids to enjoy it, and I just don't think it's right what they've done and how they've gone around it as well," Sarah says.

Not going down 'without a fight'

As Australia and the world seek to transition to renewable energy, demand for rare earth minerals has surged.

The term 'rare earth minerals' refers to a group of 17 chemical elements found in sand deposits, which are used in components of wind turbines, batteries and other technologies, such as smartphones and weapons.

But for those living on the land in north-western Victoria, which is rich in minerals, concerns exist over how rare earths mining is being conducted, as well as deep scepticism about the feasibility of environmental rehabilitation.

At former mine sites, visited by SBS News, a dried-up lake and farmland that no longer produces crops reveal signs of environmental degradation. Locals claim that despite rehabilitation efforts by mining companies, a small portion of the land has become permanently uninhabitable.

Families like the Trotters say they aren't willing to give up their farms "without a fight".

They have had preliminary discussions with Astron about selling their land, with the company proposing to buy it at "market rate", but Sarah says that option is hard to trust and impossible to accept.

"To put a dollar value on this place, I don't think you can. This place is everything to us," she says.

"You could offer anything in the world and we don't want it. We want to live here, we want to farm here, we want to raise our family here."

In 2008, then-Victorian planning minister Justin Madden said the Donald Project would have "overall economic benefits for the region and the state" as well as "net social benefit" in a report responding to Astron's Environmental Effects Statement (EES), which was approved by the government.

The project is unlikely to have significant adverse social effects and should produce a net social benefit to the local and regional communities, provided that potential adverse social effects are effectively monitored and managedFormer Victorian planning minister Justin Madden

But despite assurances, Sarah says the project has caused significant distress for several families, including her own.

"Mental health has probably been a massive issue for not only us, myself, but other people. I think it's quite upsetting to see your best mates bawling their eyes out, just not knowing what to do, how to fix this, where to go from here," she says.

"I think that's the hardest thing. We can't fix it and there's no answer at the moment and no-one has any answers."

Responding to questions about community opposition, Resources Victoria says the safety of the community, environment and infrastructure is "built into key mining approvals processes, such as the work plan for the Donald Mineral Sands Project".

"The Victorian Critical Minerals Roadmap is supporting the development of the industry, setting the right conditions to deliver maximum benefit across the state while ensuring transparency and regular engagement with local communities."

Astron has also emphasised the project's potential economic benefits, saying in a statement to SBS News it will "attract new expertise to the Wimmera while developing homegrown skills". The company says DMS plans to hire up to 100 contractors to construct the mine and an additional 100 on-site employees once the mine is operational.

The race for rare earth minerals

Rare earth minerals are described as such because they are typically dispersed throughout other mineral deposits rather than in a concentrated form. In that sense, they are 'rare', but they actually occur abundantly in parts of the world, including in Australia's Wimmera region, which has some of the most significant rare earth deposits in the country.

That's something the federal government wants to boost investment in — as do other countries.

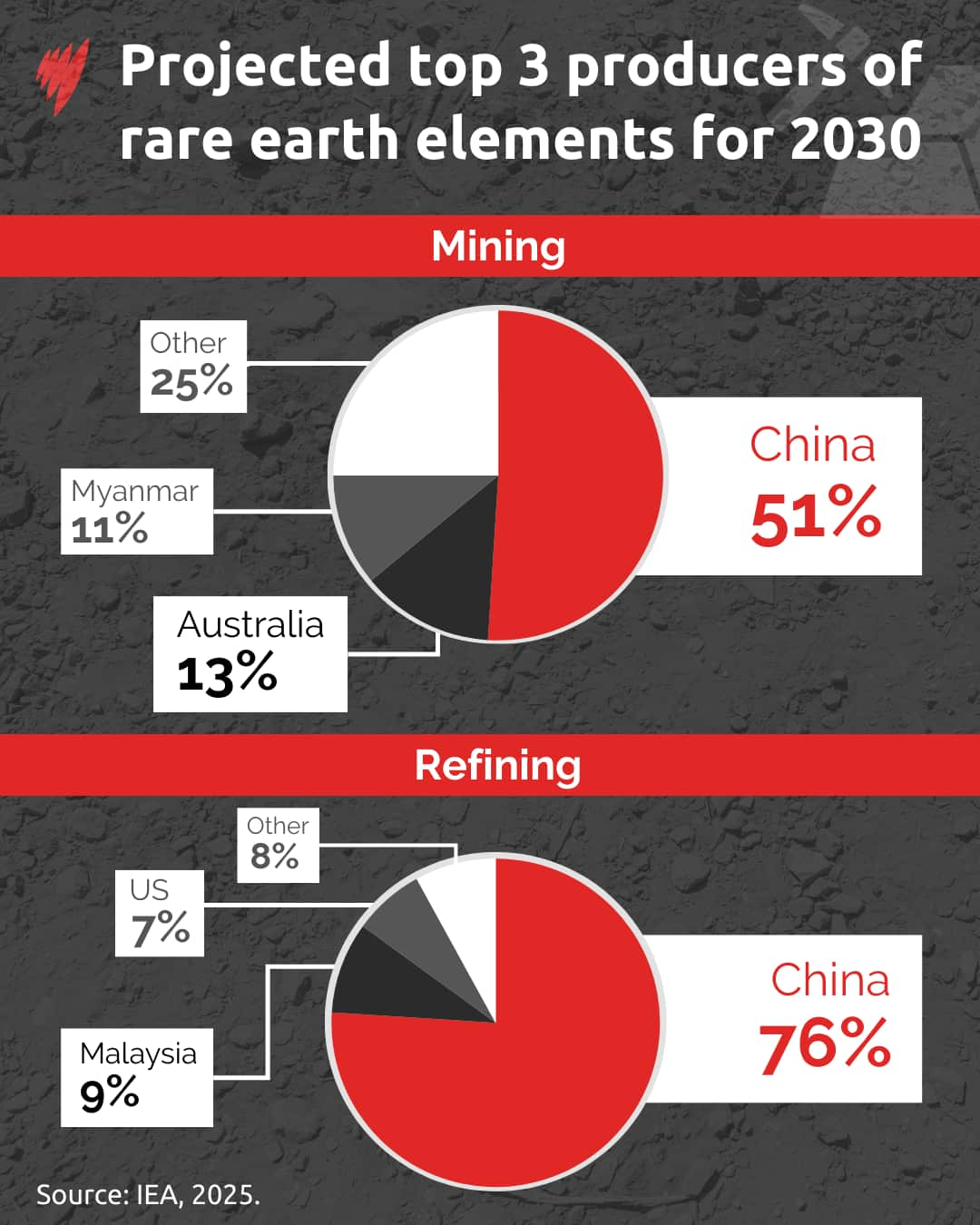

Currently, China holds a significant monopoly on the world's supply of rare earths, accounting for around 70 per cent of global mining and 90 per cent of global processing, according to the International Energy Agency. That lion's share is unlikely to change; however, over the next five years, Australia is on track to become the second-biggest producer of rare earth elements.

Earlier this year, China threatened to halt exports of rare earth minerals to the United States, amid an ongoing tariff row, after which US President Donald Trump funded billions of dollars of incentives for investors in the minerals, as part of his 'big beautiful bill'.

Both countries have a potential stake in the Donald Project — China, via Astron, which was, until last month, headquartered in Hong Kong, and the US, via Colorado-based Energy Fuels, which has committed $183 million in the venture. Astron is Australian-owned and now domiciled in Melbourne, but according to its website, it also has "in-depth experience in the China market" and has been operating a mineral processing plant in China since the 1990s.

Vlado Vivoda, honorary fellow at The University of Queensland's Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, says the US is working with its allies, including Australia, to create "alternate supply chains".

It has also been trying to build its domestic capacity for some time to compete with China.

"This was already started during the Biden administration, and it continued with the Trump administration, where they are pushing hard to produce some of these rare earths at home or get the production started in countries that are friendly to the United States where supply chains can be separated from China," he says.

According to Vivoda, the Western world is "playing catch-up to China" but it's not too late for Australia to play a role in expanding global supply chains.

"Australia has 8 per cent of the world's rare earth mineral deposits, or the fourth largest reserve in the world," he says.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in April announced an initial investment of $1.2 billion to set up a strategic reserve of critical minerals, including rare earths, which he described as key to Australia's national security "in a time of global uncertainty".

The government has also agreed to loan over $2.6 billion to two firms to establish separate refineries — Arafura Rare Earths mine in the Northern Territory and Iluka Resources in Western Australia.

But Australia's push to become a bigger player in the global race for rare earth minerals relies on digging up prime agricultural land.

Damaged Earth

Proponents of mining say the Wimmera can balance its role as a major food-growing region with the demands of mining.

But Horsham mayor Ian Ross says what happened at Iluka Resources' Douglas mineral sands mine in Balmoral, Victoria, should serve as a warning to other communities.

The mine opened in 2004 and ceased operations in 2012, but some members of the community are still dealing with unintended consequences.

The mine's EES, approved by the Victorian government in 2002, stated evidence from other mine rehabilitation sites "suggests agricultural crops on restored soils will be comparable or better than on similar non-mined landforms".

However, there are at least three sites that have not recovered from the effects of mining operations.

SBS News visited agricultural paddocks within the former mine site that have been twice rehabilitated but still can't grow crops.

Ross explains this is because the soil has not been levelled sufficiently and water drains unevenly across the once-arable paddocks, which the landowner estimates has cost millions of dollars in lost revenue.

Iluka Resources says a plan for the second rehabilitation of the site was implemented between 2022 and 2024, and "included provision for a topsoil stockpile", which the landowner could use to fix the land depressions.

Ross also accompanied SBS News to Lake Kanagulk, which is adjacent to the former Douglas mine site — and no longer resembles a lake. Currently bone-dry, the lake bed is surrounded by trees with watermarks about two metres above the ground.

Before the mine opened in 2004, Ross says Lake Kanagulk was one of the "best crayfish fisheries in the state", drawing in tourists and money to the town.

Kanagulk is an 800-hectare ephemeral wetland — meaning water isn't present all the time and it is influenced by rainfall and flows from other nearby catchments.

But in contrast to its typical water patterns, it has been dry since Iluka Resources' mine opened, Ross says.

"Because the headwaters have been cut off now for 25 years, the lake hasn't really had any water in that time," he says.

He says Iluka Resources is still diverting water away from the lake and into a freshwater dam on the mine site.

"The ecological damage is done when you don't put water in ephemeral wetlands — it's quite horrific. There's been no breeding events for any of the birds," Ross says.

The predicted impact of mining on the lake was judged to be "negligible" in the original EES, which stated the lake had had water in it in 2001, but had been "mostly dry" for years prior, and only 12 per cent of the lake's catchment would be affected.

Parks Victoria, which manages the lake site, told SBS News it doesn't have records on water levels.

SBS News also contacted the Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority, which is responsible for protecting and enhancing the land, water and biodiversity across south-west Victoria, but did not receive a response.

"It's a downside when EES's aren't done properly and the real environmental effects are not truly looked at long-term," Ross says.

Communities feeling duped

The work plan for the Douglas mine, published in 2003, specified the mine site would keep its footprint constrained to "approximately 2,000 metres long" and rehabilitated as soon as work had been completed, with the project then moving onto other sites.

Thirteen years after operations ended, Iluka Resources is still filling in Pit 23, where tailings from the mine were stored, despite the EES saying the moving and dumping of tailings would "probably" be complete within three years.

Ross also showed SBS News Pit 19, which he says used to be a plateau but is now a dirt hill covered in patchy grass. This is despite the EES stating the land would be restored to its original landform.

Ross says Wimmera residents are concerned that mining companies won't be held accountable if they don't follow their own impact statements and are allowed to revise their plans through "work plan amendments", which are readily issued by the government.

The EES said this would be [the] world's best practice mining … we got the opposite.

Iluka Resources disputes claims made by Ross, telling SBS News they are "unfounded, inaccurate and being repeated again as a part of an ideological campaign against the mining and processing of critical minerals in Victoria".

"Iluka's operations at Douglas have been comprehensively reviewed over a number of years, including 11 reports by independent technical experts and more still by regulatory authorities," a spokesperson for the company said in a statement.

"These reports have consistently confirmed that Iluka's operations in Victoria have been carried out in accordance with both federal and state legislative frameworks."

Iluka also disputes that it has diverted water away from Lake Kanagulk, or created hills where it ought not to have at Pit 19.

"We have not been made aware of any independent scientific data to indicate that our work at Douglas has compromised Lake Kanagulk," the spokesperson said, noting that a state government audit of the company's rehabilitation efforts found "a high level of compliance by Iluka".

The company has also pointed to a planning permit, initially rejected by the Horsham Rural City Council, allowing it to continue using Pit 23 for the disposal of mineral processing by-products from another of its mines. This permit was granted via an appeal at the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Iluka says the rehabilitation of Pit 23 started in 2021 and is scheduled for completion by December 2025.

Rebuilding trust

Along with the Donald Project, Victoria has seven other mineral sands mining projects at various stages of approval, describing the burgeoning industry as a "once in a generation opportunity".

Trust between some regional Victorians and mining companies is low, says Minyip resident Ryan Milgate, who lives next door to the Trotters.

Milgate says that, once operational, the Donald mineral sands mine will be visible from his kitchen window, 2.5km down the road. DMS disputes this and says it will be "about 6km" away from the property and not visible.

Milgate says he's concerned his family of four will be impacted by light pollution, noise, dust and naturally occurring radioactive material disturbed by mining, along with the disruption of dozens of trucks driving past daily.

Beyond that, he doesn't know what the potential health or other impacts may be, because he says they haven't been analysed or communicated to him.

"A lot of the community benefits that have been sort of sprouted — we're very, very dubious of, and yeah, we're just really concerned that we're not being listened to and that consultation has been non-existent," Milgate says.

He tells SBS News he has asked Astron but hasn't been presented with any scientific analysis on how his lentil crops will be affected, leaving him wondering if they will be unsaleable in the future.

"It's a really uncertain future that we're facing," he says.

They're talking about the 42-year life of a mine. When that's done, I'm gonna be nearly 90, and my kids are gonna be in their mid-50s.

"It really does concern us when there's so many unanswered questions around the impacts and issues of living next to a mine for so long," Milgate says.

He says it feels like farmers are losing out in the global race for rare earth minerals.

"It's kind of crazy like this huge global race, and it comes down to Aussie farmers, I mean, it's [Australian] government policy as well," he says.

In relation to the Donald mine project, a spokesperson for Astron told SBS News that it has sent newsletters to 15,000 locals and held regular community information sessions, as well as fortnightly "Coffees on Us" sessions in regional towns.

"We are proud of our consultation and as committed as ever to open dialogue with the community. We encourage residents to engage with us through any of the available channels," it said.

Astron says it will minimise dust and that air, noise, groundwater, radiation and visual impacts will be monitored and shared with the public, noting that the potential impacts stemming from light and noise pollution on Milgate's property are "unlikely" and that trucks will not pass by it.

The spokesperson also noted that naturally occurring radioactive materials will be handled with "fully enclosed wet processing, eliminating pathways for materials to become airborne".

As with all mining projects, DMS will be subject to regulatory checks, and the company will be liable for additional rehabilitation costs — including forfeiting its rehabilitation bond — if it fails to meet the terms outlined in its EES.

James Sorahan, executive director of the Minerals Council of Australia's Victorian branch, says mining is "very highly regulated in Victoria, as it should be".

"It's enormously scrutinised and looked at extremely closely, and I think that should give communities a lot of confidence. And at the end of the day, mining wants to do the right thing. We are part of these regional communities." Sorahan says.

'We don't know what's going to happen'

Eight kilometres outside the regional Victorian town of Horsham, also in the Wimmera region, another mineral sands mine has been proposed: WIM Resources' Avonbank project.

SBS News understands that some Horsham locals have been hesitant to share their support for the mine, fearing pushback from those vocally opposed to it.

The mine has received federal government approval, and the decision to grant a mining licence now lies with Resources Victoria following a community feedback period.

Fifth-generation farmer Scott Johns estimates that, if the mining licence is granted and the subsequent work plan approved, approximately a quarter of his farm in Dooen (a short drive from Horsham) will be directly affected, with pits dug about 40m deep.

He says the word "mining" is not compatible with sustainable farming, because it involves digging something up.

"We don't know what's going to happen," he says.

"Whether they're going to buy the land, whether they're going to lease the land, what sort of compensation we're expected to get," Johns says.

Like Sarah and Paul, Johns wants to pass the land to his children, but WIM Resources plans to acquire it for a 24/7 mining and processing operation over a 38-year period.

"When [WIM Resources employees] first arrived, we'd been through this before; this area has been surveyed many times over the last 50 years and I suppose we never really thought that it would actually happen," Johns says.

"We're talking about extremely expensive land here, the price of this country has gone through the roof in the last five to 10 years."

The 65-year-old farmer says his biggest concern is what will be left behind. He doesn't believe the land can be rehabilitated.

"I don't see myself as the owner of this country; I'm just the caretaker.

"But it's my generation's job to make sure it carries through to other ones."

Correction: A previous version of this article stated Astron Limited (formerly Astron Corporation) was based in Hong Kong. The company was redomiciled from Hong Kong to Australia on 29 August, resulting in changes to the group's registration and share listing. This has been corrected. The article has also been updated to include an additional response from DMS regarding potential impacts to Ryan Milgate's property.