The first thing Bernedette Angus does in the morning when she wakes up is check her electricity meter. Not her phone, or the weather, but a small digital screen fixed to her wall.

It shows her how much credit she has remaining before the power will be shut off.

When it hits zero, the lights go dark.

"It makes me sad and worried," she says.

"Because when my kids go to school, I have to look around for power just to cook a feed."

In the remote Western Australian community where Angus lives, households don't receive electricity bills.

Instead, they must prepay for credit — similar to topping up a mobile phone.

When the credit runs out, the power cuts instantly, with no warning, no grace period and no safety net — just a small amount of emergency credit that immediately turns into debt.

"It's devastating," Angus says.

"Between paychecks, we are always trying to save some power just to take it to the next fortnight."

The 44-year-old Bardi Jawi woman and mother of three lives in Ardyaloon — a remote Indigenous community on the north-eastern tip of WA's Dampier Peninsula – on Bardi Jawi Country.

A day's worth of power there costs around $20, Angus explains — but that can double or even triple in the warmer months.

"You got a deep freezer, a fridge, and air conditioning … and when you have kids around, you are using all three. It could be $40 a day," Angus says.

Speaking with SBS News, she pauses and turns her head towards the sea breeze.

"At the moment, I'd rather be sitting outside under a mango tree than inside here; it's much cooler," she says.

A daily countdown

About 27 kilometres south of Ardyaloon, in another remote Indigenous community — Djarindjin — Audrey Shadforth shares a similar story.

On hot days, Shadforth carefully rations her electricity — choosing between cooling her home and keeping her freezer running.

When asked how she feels about the choice, Shadforth says: "Oh, all depressed, you know."

"Because if you've got an infant in your house, you got to worry about her. And it is very hard.

"We would be calling families at night to help us out [with payment] if we have no power. But what if they have nothing?"

Power cuts have become routine in Djarindjin.

"Just one warning and then you know, we would be rushing," Shadforth says.

"Like today, I ran out of power.

"We had power all night, then about 9pm it went off. By 8.40pm, we were hurrying to look for power ... to look for some money to pay for power. That only gave me like what, [a] few minutes."

For Shadforth, each day feels like a countdown — one that resets only when there's enough money to top up again.

'No safety net'

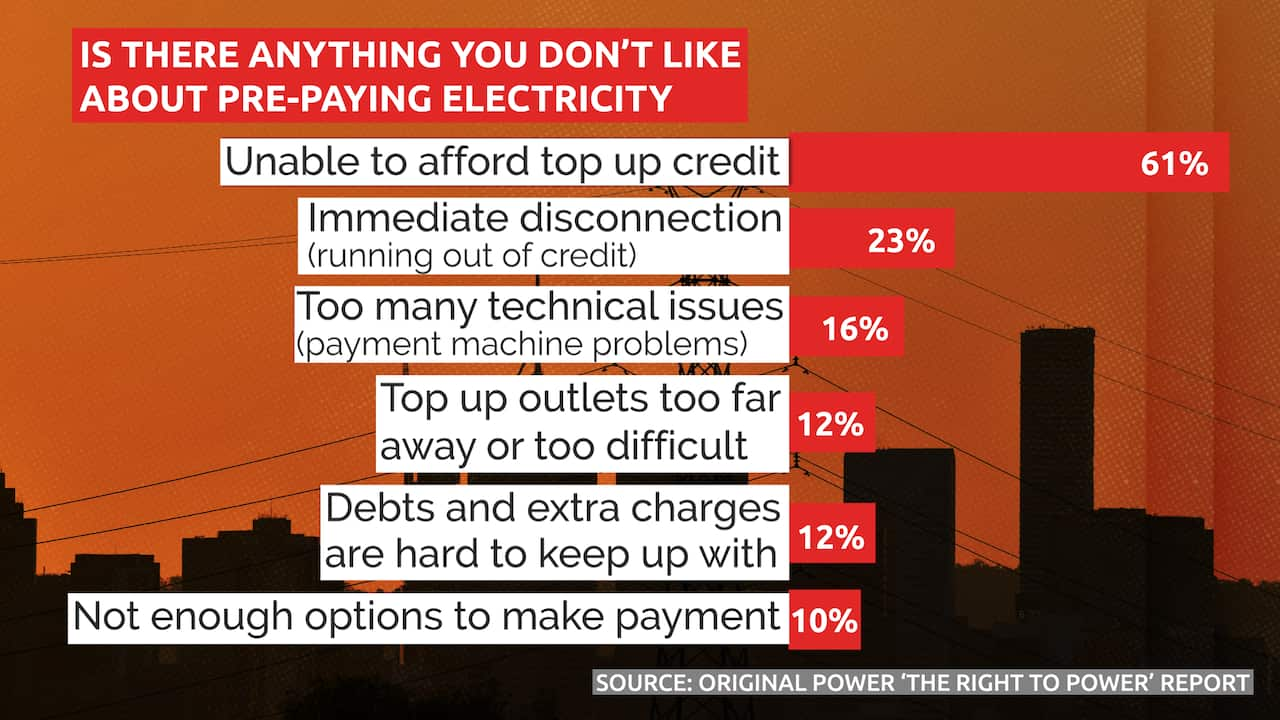

According to research by the Aboriginal community and clean energy organisation Original Power, there are around 15,000 First Nations households in Australia that rely on prepaid power. For them, prepaid is not a choice — it's the only option their energy retailer provides.

In remote areas, many households were never connected to the main power grid and have traditionally relied on small local systems, making billing and payments difficult.

To address this, power companies introduced prepaid meters, guaranteeing that bills would be covered with upfront payments.

But while city regulators, overseeing similar prepaid models in urban areas, have decided it would be too harsh to cut people off from electricity when their credit runs out, regulators in remote communities have prioritised ensuring bills are paid, rather than protecting people's right to power.

A new report released by Original Power, in partnership with Notre Dame's Nulungu Research Institute and Western Sydney University, has shed light on the scale of the problem.

The first-of-its-kind study — titled The Right to Power — found that around 65,000 First Nations people live under mandatory prepayment systems.

On average, these homes experience more than 30 disconnections a year, many of which last hours and sometimes days.

The report estimates there have been 440,000 disconnections across 8,800 households in the past year alone.

Affordability is noted as a pressing concern throughout the research, with electricity tariffs for prepaid customers ranging from 11 to 34 cents per kilowatt-hour, depending on jurisdiction.

This resulted in average annual household expenditures of about $2,500 in the Northern Territory, $3,400 in Western Australia and $1,800 in South Australia.

The findings have prompted calls for retailers to set lower tariffs and for the federal government to extend its energy relief payments, due to stop at the end of this year.

Lloyd Pigram, a researcher from the Nulungu Research Institute who worked on the study, says power outages are becoming an acute issue in remote areas.

"Old people with chronic illnesses were running out of power as we were doing the [survey] interviews," Pigram says.

"When you've got family and you are understanding that sort of stuff is happening around you ... it's hard not to get emotional or angry because you're seeing people struggling."

Some with not long left to live — and they’re still being disconnected from power.

Poor housing design and low energy efficiency can also drive up costs, Pigram explains. Many social homes in remote communities are poorly insulated and rely on old or inefficient appliances, which makes it far more expensive to keep houses cool in summer or warm in winter.

"It's a system that puts the risk back on the individual," Pigram says.

"If you run out of money, the power's cut instantly — there's no safety net."

Climate, distance and deadly consequences

Most prepaid customers in remote Western Australia must still travel to a store to buy credit — a task that becomes near impossible when roads flood during the wet season or shops close early.

As the Kimberley heads into another warm summer, with temperatures regularly surpassing 40C, the consequences of power loss can be deadly.

No electricity means no refrigeration for food or medicine, no fans or air-conditioning to help with heat stress, and limited access to communication or safety information during heatwaves and cyclones.

The federal government's National Climate Risk Assessment, released in September, named the Kimberley as one of Australia's most climate-vulnerable regions and warned poor housing quality and isolation compound the risks.

Today, a series of recommendations is set to be heard in parliament, based on findings from a report led by Original Power and the First Nations Clean Energy Network.

The 115-page report calls for six key reforms — including a ban on disconnections during extreme heat and a national definition of financial hardship that includes prepaid customers.

It also urges governments to trial a summer protection scheme, ensuring prepaid households remain connected during dangerously hot weather, with lost revenue reimbursed through public funding.

The report estimates the total annual cost of keeping those households connected during extreme heat across the NT, WA and SA is around $1.57 million — a figure that represents up to 95 per cent of the National Energy Bill Relief Fund expenditure for the same period.

Urgent calls for reforms from all sectors

In a statement to SBS News, Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said the government has received the report and "appreciates the information it provides about energy security issues in remote communities".

"Energy is an essential service ... regardless of where you live or how it's paid for," he said.

"We're working to make sure all communities get a fairer deal, and can share in the benefits of Australia's renewable future."

However, Bowen said regulation of off-grid systems remains the responsibility of state and territory governments.

A Western Australian government spokesperson said the government will consider the report's recommendations.

"Since taking responsibility for electricity in 117 remote Aboriginal communities, Horizon Power has been rolling out advanced metering technology to regularise power supply, improve safety, and give customers more choice and control over their energy," the spokesperson said.

This is a long-term commitment to Closing the Gap, ensuring every community, no matter how remote, has access to safe, reliable and affordable power.

"Its Kimberley Communities Solar Saver is a pioneering program which is delivering energy equity to remote communities in the Kimberley," the spokesperson said.

The Northern Territory government said it would also review the report and "consider any recommendations that help improve coordination or simplify the application process" for relief programs.

State-owned retailer Horizon Power, which services more than 100 remote WA communities, including Ardyaloon and Djarindjin, said it offers hardship assistance and in-home energy coaching through its Energy Ahead program.

"We proactively engage with vulnerable customers to provide case-managed support," a Horizon Power spokesperson said.

"While Horizon Power is broadly supportive of the intent of the Original Power report, its recommendations deal with policy matters, and it would not be appropriate for Horizon Power, as a Government Trading Enterprise, to provide any comment."

Community support

Despite the hardship, Angus says her community will always look out for one another.

"That's what Ardyaloon families do, they help each other out.

"Even today, someone caught a turtle and we all went there, bring us up, to come over for a feed. So nobody starves."