When asked what most prepared her for the world of politics, the woman once recognised by the European Parliament as "president-elect in the eyes of the Belarusian people" has an answer that many parents may empathise with.

"I always say, raising two children — you learn negotiation, crisis management and how to survive on very little sleep," Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said at an event late last year in Melbourne.

For now, however, she's raising her two children in exile, having fled the country ruled by the man often referred to as 'Europe's last dictator', President Alexander Lukashenko, who has held power since 1994.

That year's poll has been described as "the country's only democratic election" by the United States-based pro-democracy NGO Freedom House, and international election monitors generally consider none of the subsequent six elections free or fair.

Tsikhanouskaya's 2020 challenge of Lukashenko — undoubtedly the continent's longest-reigning contemporary autocrat — transformed the then 37-year-old former English teacher into the most recognisable figure of Belarus' pro-democracy movement.

According to official results — disputed by Tsikhanouskaya's movement and independent observers — Lukashenko won a sixth term with more than 80 per cent of the vote.

Under pressure from security forces, Tsikhanouskaya fled to Lithuania that year, where she has continued to advocate for political prisoners, support Belarusians, and forge international alliances.

From exile, her team is creating alternative governmental institutions, such as the United Transitional Cabinet of Belarus, a body formed in 2022 as a bridge towards democratic governance in the state that borders Ukraine to the south and Russia to the east.

While Australian political representatives have cast doubt on the 2020 election and expressed support for Tsikhanouskaya, Australia's policy remains to recognise states, not governments.

The 2020 election and uprising in Belarus

Tsikhanouskaya told an audience at Melbourne's Swinburne University in early November the story of how the 2020 arrest of her husband, video blogger Siarhei Tsikhanouski, kick-started her political career.

"I never planned to run for office … It was my husband, Siarhei, who wanted to run," she said.

"He travelled the country asking people what was happening in their lives. The answers revealed corruption, injustice and fear. For simply listening to people, my husband was arrested."

With her husband locked up and awaiting an uncertain fate, Tsikhanouskaya decided to run in his place.

Even before she'd collected enough signatures to register for the presidential race, she started receiving threats.

"I got a phone call saying, 'You'd better stop doing that, or else you will be arrested and your children will go to an orphanage, since both of their parents will be behind bars,'" she told The New Yorker in a December 2020 article.

Tsikhanouskaya said Lukashenko allowed her to run as he didn't think a woman would be a viable candidate for president.

"The dictator registered me as a candidate, but he didn't believe for a second that I might win," she said.

"'Our constitution is not for women,' he said. But I think he was absolutely wrong."

Lukashenko's claim of an 80 per cent victory in the August ballot was widely dismissed at home and abroad. The European Union Council called the election "neither free nor fair" and said Lukashenko's mandate "lack[ed] any democratic legitimacy".

"The elections were valid. There could not be more than 80 per cent of votes falsified. We will not hand over the country," Lukashenko said, as reported by British newspaper The Telegraph.

Belarus was quickly swept by the largest protests in its modern history — and a violent government crackdown.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch estimated that hundreds of thousands of Belarusians took to the streets at the peak of the demonstrations.

The Human Rights Centre Viasna reported more than 30,000 people were detained between August and September 2020.

The United Nations documented thousands of cases of torture and ill-treatment, and at least four deaths linked to the state's use of force against protesters.

Following the election, Tsikhanouskaya was detained for seven hours at Belarus' election authority headquarters, where she'd gone to formally challenge the announced results.

She left for Lithuania just hours later, after security officials pressured her to depart, giving her only "20 minutes to pack", as she later recounted.

"I was told I had to choose between my children and prison," she told The New Yorker.

In October of that year, the European Parliament recognised Tsikhanouskaya as "president-elect in the eyes of the Belarusian people" and said that the Coordination Council for the Transfer of Power — a body she set up to oppose the election results — was "the legitimate representative of the people of Belarus".

For the almost four years her husband was in detention, Tsikhanouskaya was often kept in the dark about his whereabouts.

Tsikhanouski was released on 21 June 2025, one of 14 political prisoners pardoned under a US-brokered deal involving a loosening of sanctions on Belarus.

Repression, Russia and the war in Ukraine

Inside Belarus, repression has continued to deepen since the post-2020-election protests.

Human rights groups say over 1,100 political prisoners remain behind bars, including activists, journalists, trade union leaders and ordinary citizens.

"Belarus hasn't seen such terror since Stalin's time," Tsikhanouskaya said.

In 2023, Tsikhanouskaya was tried in absentia in Belarus and sentenced to 15 years for treason, inciting social hatred and attempting to seize power through bodies like the Coordination Council.

"15 years of prison. This is how the regime 'rewarded' my work for democratic changes in Belarus," Tsikhanouskaya wrote in a social media post at the time.

"But today I don't think about my own sentence. I think about thousands of innocents, detained & sentenced to real prison terms. I won't stop until each of them is released."

Lukashenko's government has called her movement an "extremist" group and said Belarus' national security is harmed by its calls for sanctions against it, some of which Australia has imposed.

Belarusian writer and activist Tony Lashden told SBS Russian in March 2025 that the state's use of violence has become universal.

"After 2020, everyone in Belarus understands what violence looks like — how it appears when it comes from the state," she said.

Lashden said censorship has tightened so much that "people are physically losing access to the internet or to independent media".

"Simply accessing information not funded by Russian propaganda has become a form of digital activism," she said.

Reporters Without Borders refers to Belarus as "Europe's most dangerous country for journalists until Russia's invasion of Ukraine", saying the country "continues its massive repression of independent media outlets".

In 2025, the group's World Press Freedom Index gave Belarus a score of 25.73 out of 100, placing it at 166th out of the 180 countries included in its analysis.

Freedom House's country report for Belarus also points to a broader system of digital repression, including prosecutions for routine online activity, expanded state surveillance, and intensified restrictions on VPNs and anonymity tools.

As domestic repression intensified, Lukashenko leaned further on Russia.

Russia provided Belarus with political, economic and security support, and its troops were stationed in the country ahead of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine ordered by Russian President Vladimir Putin in February 2022.

Since then, Belarus has supported Russian military logistics, training and missile launches. In 2023, Russia struck a deal to station tactical nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory,

While Lukashenko has vowed to commit no Belarusian troops to the conflict, he confirmed in December that Russia's nuclear-capable 'Oreshnik' ballistic missile system had been deployed to Belarus and entered active combat duty.

In an interview with SBS Russian in November, Tsikhanouskaya said Lukashenko's alignment with the Russian government does not reflect the will of Belarusians.

She noted that partisans and cyber-activists continue to resist despite the risks — from slowing Russian troop movements in 2022 to documenting alleged abuses and supporting political prisoners' families.

"Any act of solidarity can lead to five, 10 or 15 years in prison," she said.

British think tank Chatham House polled 833 voting-age Belarusians inside the country in December 2024, finding nearly a third of those surveyed supported Russia's war against Ukraine, while 40 per cent did not.

Meanwhile, some 36 per cent said they intended to vote in the 2025 presidential election, down from 75 per cent in 2020.

More than half of the respondents said there was no point in voting because they believed the result was predetermined.

Lukashenko was declared the victor of the 2025 election with 88 per cent of the vote — a result declared a "sham" in a joint statement issued by Australia, Canada, the EU, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

"Recognise these elections or not: It's a matter of taste. I don't care about it. The main thing for me is that Belarusians recognise these elections," Lukashenko said in response, as reported by Radio Free Europe.

The Chatham House survey found about a third of those polled were "pro-government", 41 per cent "neutral" and 14 per cent "pro-democratic".

The group warned that surveys in Belarus are "subject to distortions because some respondents fear expressing critical views toward the authorities".

Official state polls, viewed as unreliable by outside observers, routinely report overwhelming trust in Lukashenko and satisfaction with recent election outcomes.

Building a government in exile

Tsikhanouskaya said some priorities of her government-in-exile include building diplomatic relationships and filling the gap left by Belarusian embassies.

It was for this reason that she accepted the invitation from Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to visit the country in November.

During several days in Canberra and Melbourne, she met with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Foreign Minister Penny Wong, and former prime ministers Scott Morrison and Tony Abbott.

"Despite Australia being so far away, I saw a genuinely strong interest in our visit," Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian a week after returning to Europe.

During the visit, Wong issued a statement condemning "the Lukashenko regime's human rights violations in Belarus and its continued denial of the civil and political rights of the Belarusian people".

Tsikhanouskaya said one of her priorities was establishing parliamentary 'For Democratic Belarus' groups, similar to advocacy groups such as the Parliamentary Friends of Palestine and the Australia-Ukraine Parliamentary Friendship Group.

"[For Democratic Belarus] groups already exist in 24 countries … They organise hearings on Belarus, meet with Belarusians living in a particular country, listen to their concerns and look for joint initiatives," she said.

"We would be very glad to see Australian representatives at the next gathering of the For a Democratic Belarus parliamentary groups in London next year."

'We want no Belarusian to remain invisible'

One of the most urgent challenges for Belarusians abroad is keeping their passports valid, Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian.

"The Lukashenko regime has banned embassies from issuing new passports … If it is unsafe to return home, their passport expires and they have no way to renew it," she said.

The change, which was formally signed in September 2023, is part of "optimising" consular work, according to the decree's explanatory note.

Australia-based Belarusian Ilya Kavalchuk told SBS Russian the policy forces many into an impossible choice.

"Consulates have stopped helping Belarusians abroad with any legal procedures … Their passports simply expired — and going back to Belarus means a real risk of being jailed," Kavalchuk said.

The problem is particularly acute given the number of Belarusians who have fled the country since 2020 — although precise figures remain uncertain.

"Figures vary between 300,000 and 500,000, undoubtedly the largest migration movement in the history of Belarus since [the] Second World War," according to a June 2023 report by the Council of Europe's Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons.

Tsikhanouskaya's team told SBS Russian that, based on post-2020 migration levels, an estimated 40,000-75,000 Belarusians cannot return without risking arrest, and many now have expired passports due to the country's 10-year passport validity period.

In her interview with SBS Russian, Tsikhanouskaya warned the situation could soon escalate into what she described as a "humanitarian catastrophe", saying "at least half a million Belarusians who were forced to leave and cannot return will effectively be left without a country — without citizenship".

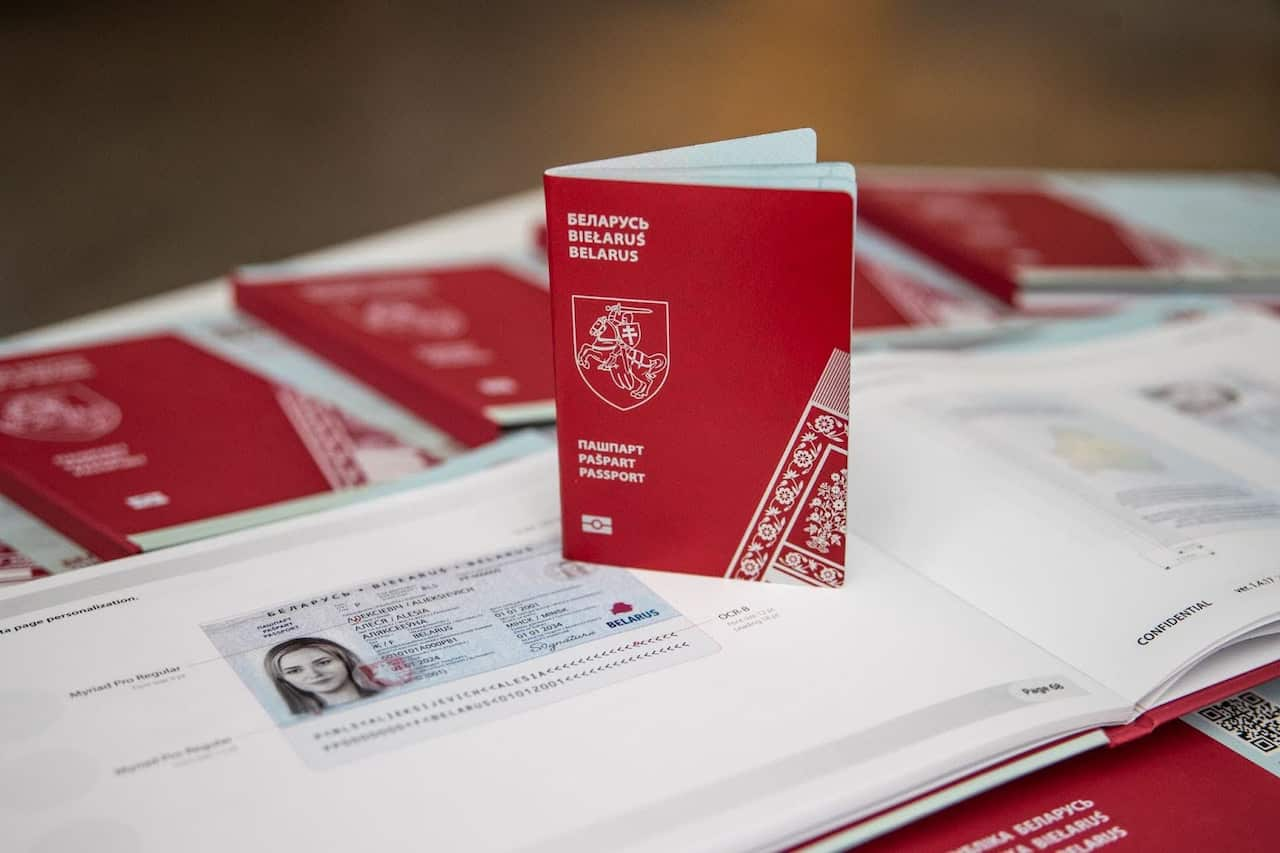

In response, Tsikhanouskaya's office has launched the New Belarus Passport project, hoping their passport will "serve as an identity document confirming Belarusian citizenship and, potentially, a travel document".

"We want no Belarusian to remain invisible to the world," she said.

The first biometric passports have been issued and the group is negotiating for their international recognition.

Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian that, "at the moment, it is more of a symbolic document", but hopes it will gain formal recognition.

"As the need [for Belarusians to have active passports] grows, we hope our allies will take a systematic approach to this issue."

Kavalchuk called the initiative "a good idea" but said it is not yet widely functional: "In Australia, the US and even parts of Europe, it's not enough to open a bank account or maintain residency."

'History is not written by dictators'

One of the central factors that will shape Belarus' future is the outcome of the Russia-Ukraine war, Tsikhanouskaya said.

"It's so important in our region that Ukraine wins … It'll weaken Putin a lot, hence will weaken Lukashenko," she told SBS Russian.

Her team is preparing for "a window of opportunity … when Lukashenko is weak enough to get rid of him", including outreach to officials, elites and military figures.

If Russia emerges stronger from the war, Tsikhanouskaya's struggle will be harder. But she still hopes her family will one day return to the country of her birth, perhaps entering with a 'New Belarus Passport'.

"I believe that my children will go back to Belarus, and I believe that political prisoners will walk free and the truth and justice will prevail because history is not written by dictators, it's written by people."

SBS News contacted the Belarusian embassy for comment but did not receive a response at the time of writing.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.