Two years ago, a friend and I were couchsurfing in Iraqi Kurdistan. We found ourselves in the southern city of Sulaymaniyah, which these days is not far from the front line against ISIS. Historically, it has been cultural centre for the Kurdish people; geographically it is achingly close to the ‘Kurdish Jerusalem’ of Kirkuk, last year retaken from Iraq and ISIS, and Halabja, the horrific site of Saddam’s chemical attack on civilians in 1988.

The city presents a cobweb of lights best viewed at night by escaping the heat in the surrounding mountains with some cold beers. The mountains of Sulaymaniyah have long been friendly to the the famed Kurdish militia, the Peshmerga. Peshmerga means in Kurdish 'those who face death', in practice it means ‘freedom fighter’. They've become best known to the West through their recent battles against ISIS in Sinjar and Kobane.

Sulaymaniyah’s Red Prison housed the Ba’ath Party intelligence agency and was infamous as a house of torture of the Kurdish people. The prison is now a museum to the horrors of the regime. Out the front, Soviet-era tanks and armoury stand to attention in a perfect row. One of the first rooms we entered showed plaster figures depicting the torture of a man on his back on the dirt floor, tied to a pole, his feet being whipped. The soles of the feet are a reoccurring theme in torture prisons: humiliation is as important as pain, and a man who can’t walk is automatically a reduction of himself. There aren’t many travelers in Sulaymaniyah, so we walked through the prison alone and in solemn silence until we saw a middle-aged man with his wife and two young sons. Our friend Miran began translating. “That man was in here. He’s brought his sons here to show them.”

There aren’t many travelers in Sulaymaniyah, so we walked through the prison alone and in solemn silence until we saw a middle-aged man with his wife and two young sons. Our friend Miran began translating. “That man was in here. He’s brought his sons here to show them.”

His name was Barzan; he was Peshmerga. Barzan was interned twice in the prison. As a matter of course, he was tortured. He wanted to tell us his story, too. We passed the tiny solitary confinement cell, to which Barzan had been sent several times. Most of the prisoners spent time in there at some point, and passed on the knowledge the cell width was leg length – so if one propped themselves up with their backs against the wall and their legs at a right angle, they could get high enough up to see out the tiny window at the top. They could see the mountains, and more importantly, the birds that flew past. Nature, the moving world outside, was what kept them going inside that tiny cell. A little plaster bird now sits in the window.

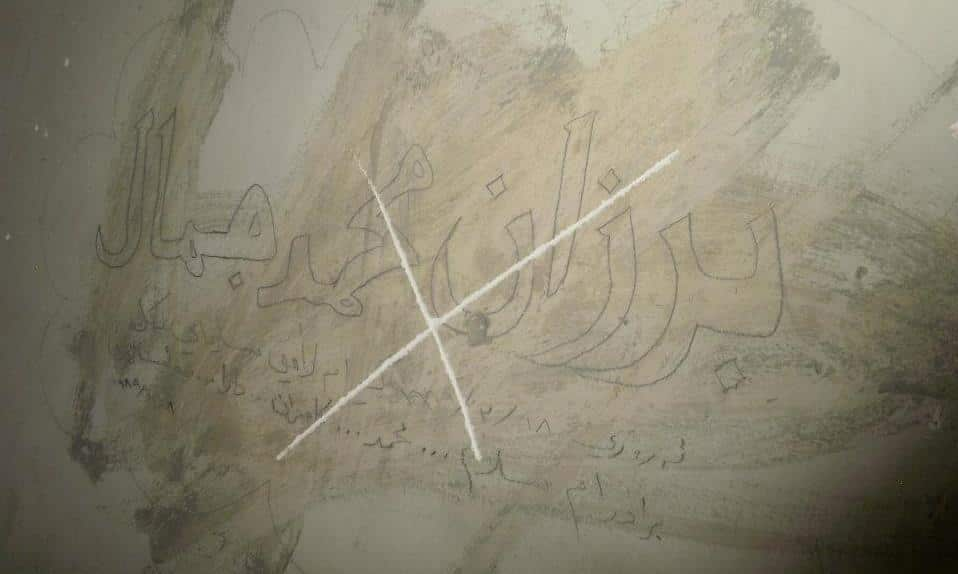

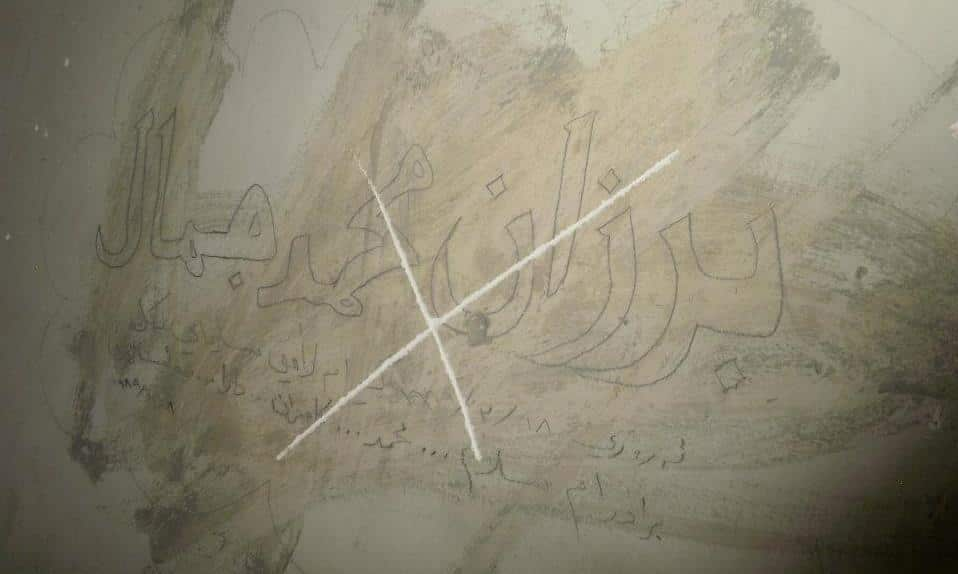

Barzan also found his former cell and was surprised to see his graffiti was still on the wall. He wrote: Barzan Muhammad Jamal, 18.03.1989. I was arrested with my friends, Salam, Muhammad, Kamaran and Dara. As someone who puts words after each other for a living, I struggle to explain the joy found in seeing those few words strung together on the wall. Finally, we walked into another room with a plaster man hanging from a horizontal pole suspended close to the ceiling. Barzan told us that was the one that broke him. In the Renaissance it was known as the strappado, these days it is known as a ‘Palestinian hanging'. The body is suspended by the wrists that are tethered to the pole. The body’s weight does the damage as joints pop and eventually when their strength dies, the victim hangs and his breathing is compromised. Barzan recalled hanging for days by his broken shoulders.

Finally, we walked into another room with a plaster man hanging from a horizontal pole suspended close to the ceiling. Barzan told us that was the one that broke him. In the Renaissance it was known as the strappado, these days it is known as a ‘Palestinian hanging'. The body is suspended by the wrists that are tethered to the pole. The body’s weight does the damage as joints pop and eventually when their strength dies, the victim hangs and his breathing is compromised. Barzan recalled hanging for days by his broken shoulders.

The US Senate recently released a report on the torture activities of the CIA in Iraq. It concluded that which can sadly only be described as known and obvious. Torture doesn’t provide information; it is inhumane; it employed some of the same tactics as the regime that tortured Barzan. It used the pole, it conducted 'Palestinian hangings'.

There’s at least one known death from the practice, Manadel al-Jamadi, in the notorious Abu Ghraib prison in 2005. It is a false equivalence to compare George W Bush's America to Saddam Hussein's Iraq, but the horrible ironies run deep: the US reduced itself to some of the tactics employed by the regime it thought so vile to oust; it rejected the founding ethos of the US against totalitarian excesses. Any offence in Saddam’s Iraq was prosecuted as an offence against Saddam himself. The post-September 11 environment saw that offences against American values had to be personalised too; they required physical punishment . Every prisoner potentially knew of a ‘ticking bomb’.

Any offence in Saddam’s Iraq was prosecuted as an offence against Saddam himself. The post-September 11 environment saw that offences against American values had to be personalised too; they required physical punishment . Every prisoner potentially knew of a ‘ticking bomb’.

‘America’ in many parts of the world had been an abstract notion: it represented values antithetical to many other cultures, it represented the imperialism that had begun many of the geopolitical problems we know all too well today. The CIA’s torture program changed that, and confirmed to some that ‘America’ was not an abstract but an actual enemy to be resisted at every opportunity. It gave people ammunition to believe that the great liberal democracy was not a liberator but a tyranny.

The Iraq War was nowhere near as unjust as history will have it, but its execution was quite the opposite. While not on the level of Saddam’s regime, the enduring effects of the torture committed by the CIA will cast a long shadow. But this does not excuse us from vigorously prosecuting the routine acts of torture committed by the Saddam-like regimes of the world by existing mechanisms such as the International Criminal Court and the doctrine of Responsibility to Protect.

For all its history, the survivors of torture are rarely granted an audience. We need to listen to people like Barzan, not to present torture as a theatre, but to stop the ritual and the rhetoric. The writer and philosopher Hannah Arendt found a mode of optimism against what she called ‘totalitarian holes of oblivion’: “one man will always be left alive to tell the story.”

Elle Hardy is a freelance writer.

Share