Social media was abuzz last week with claims that Education Minister Christopher Pyne dropped the c-word on the floor of the House of Representatives – but he says the uttered the word "grub".

What if this audio were evidence in a murder trial?

Can proper phonetic analysis resolve the debate about what he really said – or is it just a "battle of the ears"?

This social media frenzy can tell us more about the serious problems encountered in the use of indistinct covert recordings in criminal trials - here's why.

Here’s the audio

The full clip

The sentence

The word

Here's the analysis

The entire pre-vocalic (before the vowel) portion of the word is masked by a cough. This can easily give the impression of a velar (back of the throat) consonant, like /k/.

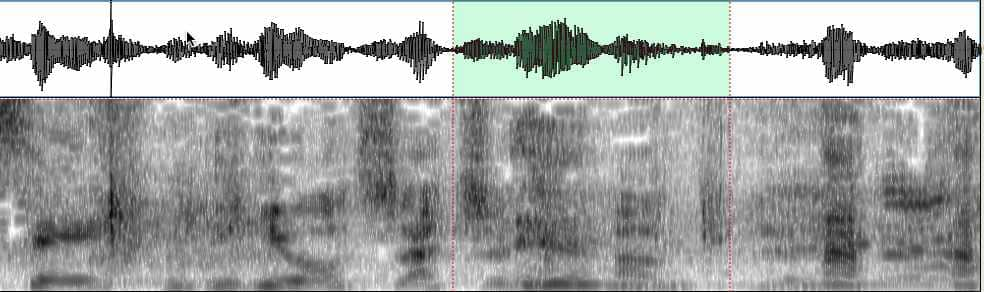

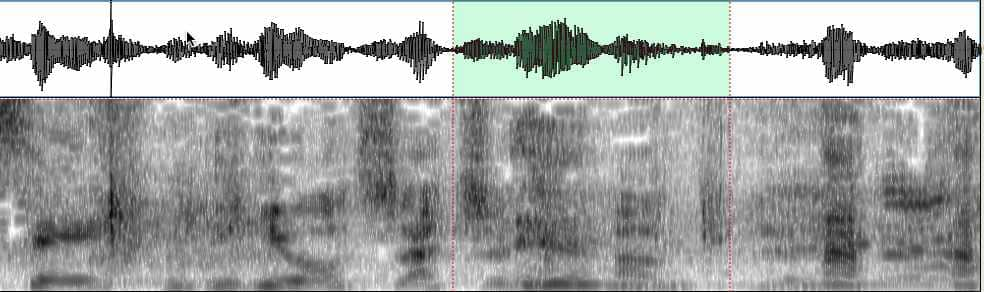

Here’s a waveform and spectrogram with the cough and the last part of the word highlighted. A couple of things to notice about the end of the word:

A couple of things to notice about the end of the word:

- All formants (horizontal dark bands) trend downwards through the vowel – suggesting the following consonant is labial (made with the lips, like /p, b, m). If it were alveolar (like /t ,d, n, s) we would expect F2 to bend upwards from its low position in the vowel.

- The consonant burst centres around 3kHz – again suggesting a labial. For an alveolar we would expect a burst above 5kHz.

These observations do not confirm "grub" as a definite, accurate transcription (especially when we cannot see or hear the first part of the word). But they do suggest "grub" as a far more likely transcription than the c-word.

We must also take into account the fact that no one in parliament at the time reacted to Mr Pyne’s epithet in a way that suggested he had uttered an obscenity. Sadly, one parliamentarian calling another a "grub" attracts no more than the mild rebuke - but using the c-word would be met with swift condemnation. The whole drama arose from someone listening to the audio after the fact.

So why are so many people sure they hear the c-word?

This is a classic demonstration of the power of priming (our tendency to hear what we expect to hear). Note that priming doesn’t require explicit suggestion of the word; our ears are generally primed to hear rude words. For example, I quite often get startled by the f-word, only to realise the person had innocently said ‘If I can just …’.

It is genuinely hard to "un-hear" something once you have "heard it with your own ears". That is true even if you know for sure that what you hear can’t possibly be correct.

How much more so when what you think you heard fits a preconceived notion you believe to be valid. It is striking how many people who claim to hear the c-word are those that don’t like or trust Christopher Pyne and are happy to believe he would have said something like this.

Why it is not safe to ask a jury to evaluate indistinct audio

This might seem like a light-hearted matter but similar issues really do affect criminal trials on a regular basis. Here’s just one example of audio from a real murder case, including a demonstration of how it was mis-heard in a way that had very serious consequences.

That is why it is so important to re-consider our current law, which considers evaluation of competing transcripts of forensic audio with life-or-death consequences to be "a matter for the jury".

Follow the links for a few examples of some issues in this area:

- Some problems with the law?

- The 1958 priming experiment

- The crisis call experiment

- The PACT experiments

- Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman

On the lighter side

A mondegreen is the mishearing or misinterpretation of a phrase as a result of near-homophony, in a way that gives it a new meaning.

Here is a collection of original mondegreens put together into a truly hilarious act – which also carries a deeper message in relation to forensic recordings. Note how real the suggested interpretations sound even when you know they cannot possibly be correct. These kind of priming effects are not quite so funny when they can mean a jury might confidently hear a confession that was never really made.

Dr Helen Fraser studied phonetics and linguistics at Macquarie University and the University of Edinburgh, then lectured for many years at the University of New England (Australia).

She has researched the theory of cognitive phonetics since the 1980s, but from 1999, has become more and more concerned with its practical applications. She now focuses mainly on two specific applications: intercultural speaking and listening, and forensic transcription.

Share