A fleet of small, white, open-air buggies take in the sea air at the edge of the docks, their drivers nonchalant, clouded in cigarette smoke, loitering in wait for an easy fare. I spent the night on the deck of the La Paz Star, crossing the Sea of Cortez from Baja California and using my leather duffle bag as a pillow, and am in no mood to shop around or haggle. I allow myself to be solicited, to be taken for a ride both literally and figuratively.

I am in Mazatlán, on Mexico’s Pacific coast, for the first time four years and ask to be driven along the malecón, or esplanade, for old time’s sake. Very little appears to have changed. A handful of late-autumn diehards take to the water. Men in hardhats and fluorescent vests install electrical wiring beneath the footpath. The Frankie Oh nightclub, once owned by the Tijuana cartel’s Francisco Arellano Félix, remains in ruins, though its facade is slighter blacker than before, charred, having caught alight two years ago.

"Do you guys still do narco tours?" I ask the driver.

"Narco tours? How do you know about narco tours?"

"I took one when I was here four years ago."

I had been covering Mexico’s drug war and the weird culture that has grown up around it. Mazatlán’s narco tours—unofficial excursions on which taxi drivers take sightseers to murder sites, shootout locations and the holiday homes of the drug lords—suited the brief nicely.

Over the course of two hours, the bodies piled up: five people were gunned down in this factory, two people were burned alive in this house, this is where Félix’s brother, Ramón, was killed in an impromptu firefight with a police officer. Before too long, one couldn’t see the trees for the forest: my driver, Tomás, spoke too fast, the body count was too high.

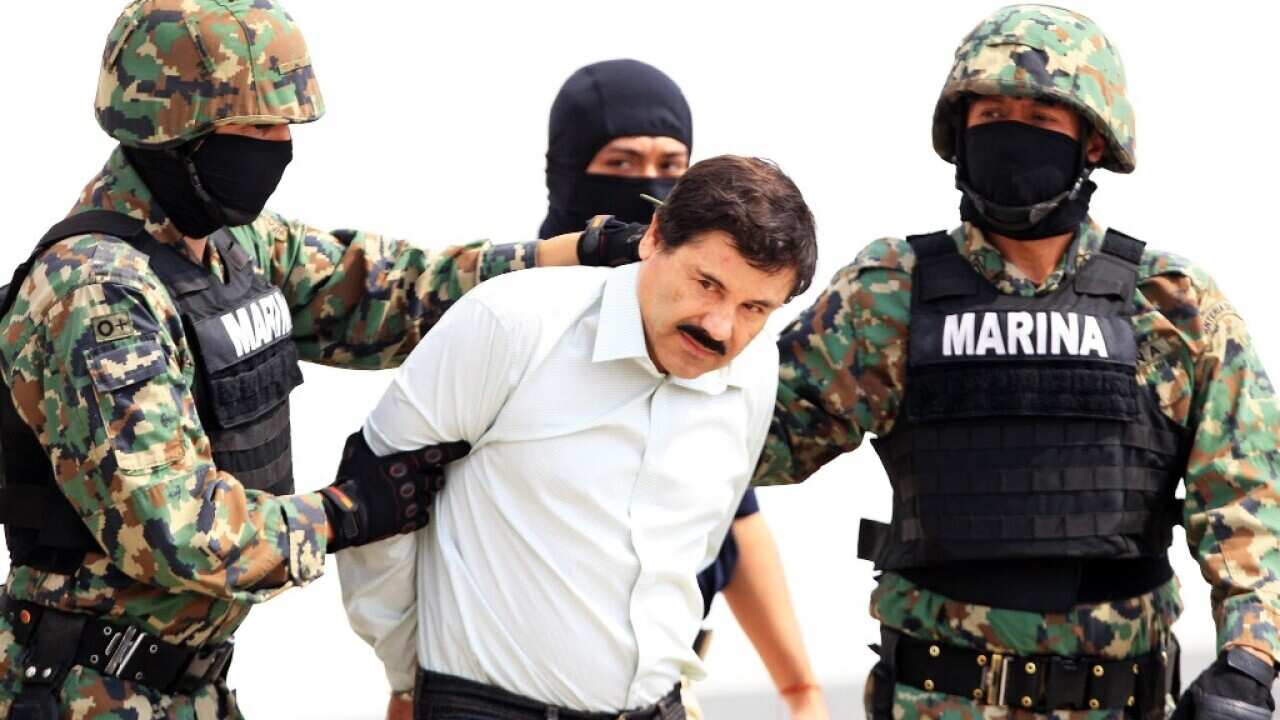

"Sure," today’s driver shrugs. "We still do narco tours. People don’t ask for them as much as they used to, but we still do them." As if to prove his credentials, he points to a pastel-yellow condominium complex, the Miramar, coming up on our right. "That’s where Chapo was arrested," he says.

In 2011, after Osama bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad, Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán Loera unofficially became the world’s most-wanted criminal. (The FBI and Interpol don't rank the fugitives on their most-wanted lists; Forbes magazine, in addition to ranking the world’s richest people, does. Until he was arrested, Guzmán regularly appeared on both the magazine’s lists.) He was arrested on the fourth floor of the Miramar in February without a shot being fired.

"What do you think of Chapo?" I ask.

"He’s a great man," the driver says. "A great champion of Mazatlan and Sinaloa." He points to a row of freshly-planted palms swaying gently in the breeze. A bulldozer a little further up the avenue is lowering another into the dirt. "The malecón would not be as beautiful as it is today without Chapo’s influence and money," he says. "He helped the poor as well, you know. A great man."

I’m not at all surprised to hear this. Like Colombia’s Pablo Escobar before him, Guzmán actively cultivated a reputation for largesse, charity and community spirit, which analysts believe may have helped him evade arrest for so many years. There are stories of him confiscating people’s phones whenever he entered a restaurant and then picking up everyone’s tab for the inconvenience when he was finished with his meal. My driver is certainly not alone in considering him Mexico’s Robin Hood.

While Chapo’s reputation may or may not have been earned, it is undeniable that the drug trade is integral to many local economies, providing employment in areas where there is little work to be had and bankrolling social services such as education and healthcare. It has been estimated that some 3.2 million Mexicans ultimately depend on the trade for their livelihood. That number includes the nearly half a million people employed by the cartels, but not those—equally dependent, in a way—who have been employed in the fight against them.

Meanwhile, the US Department of Homeland Security believes that traffickers send as much as $US29 billion back to Mexico every year from the United States, even as governments on both sides of the border have tightened banking regulations to combat the phenomenon. In 2010’s Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the Global Economy’s New Killing Fields, Charles Bowden estimated that between thirty and sixty per cent of the city’s economy ran on such laundered drug money at that time.

This is the great contradiction of Mexico’s war against the cartels: to win it would be to dismantle the country’s second largest industry after oil, stemming its massive capital flows and, perhaps, hobbling the legitimate economy in the process.

Perhaps this is why the war often feels as though it is being waged only reluctantly. It’s about keeping up appearances: making a show of high-profile arrests without ever dismantling the cartels at the root, picking and choosing one cartel over another, littering the desert with checkpoints in a show of strength that is unlikely to turn up even a dime bag.

The bus from Hermosillo to Mexicali has stopped for the second time in as many hours. An unsmiling man in desert fatigues inspects x-ray images of our luggage while another clambers through the underbelly of the vehicle with a torch. A family is asked to produce its passports, lest its members are planning an illegal crossing. Another is asked to explain why it’s travelling with several boxes of what appear to be household appliances. The man at the x-ray machine goes through a young women’s valise, emptying it of her undergarments and spreading them out on the table in front of him. The man inspecting the bus asks to inspect its engine.

Mexico’s northern deserts can at times feel like one giant, sprawling border crossing, a preventative net designed to catch everyone and everything that might reflect badly upon the country were it to reach the official demarcation. It’s literally a military operation: a hundred trucks stretch down the highway into the night, dozens of buses pull up into inspection bays, the trunk of each private vehicle is searched. No one doing the searching is unarmed.

Nor are they particularly interested. There is something rote about it all, performative. These dull-eyed federales are simply going through the motions, warding off censure from the behemoth to the north with a show, however empty, of due diligence. Is it really in their interest to curb the flow of narcotics if doing so will curb the flow of capital back south?

Perhaps not. But they certainly make things easier at the border by pretending that it is: the assumption of those at passport control is that most of their work has already been done for them. Indeed, to my surprise, Mexicali to Calexico is one of the most relaxed international borders I’ve ever crossed, the level of scrutiny far lower than it was, or seemed to be, in the desert the night before.

"What the hell were you doing in Mexico?" The usual question from the man with the stamp. A perfunctory answer. I don't tell him I'm a journalist.

There’s nowhere in the customs building to change my pesos into dollars. I guess I'll have to launder them in town. I go outside and wait for the bus. It's just past six o'clock in the morning.

The sun rises bright and cold over the United States of America.

Share