Broken Hill’s mosque is hard to find, even when you’re looking for it.

“I can still see him carrying a hurricane light down here in the nighttime, and he’d say his prayers.”

Located on a quiet suburban block near the outskirts of the city, it’s a small building painted rust red in the colour of the desert.

Amminnullah Robert Shamroze said the block, just a few streets from his home, once looked very different.

“It was all camel yards, all the way round here in little huts,” he said.

His grandfather was the last Mullah at the mosque.

“I can still see him carrying a hurricane light down here in the nighttime, and he’d say his prayers.”

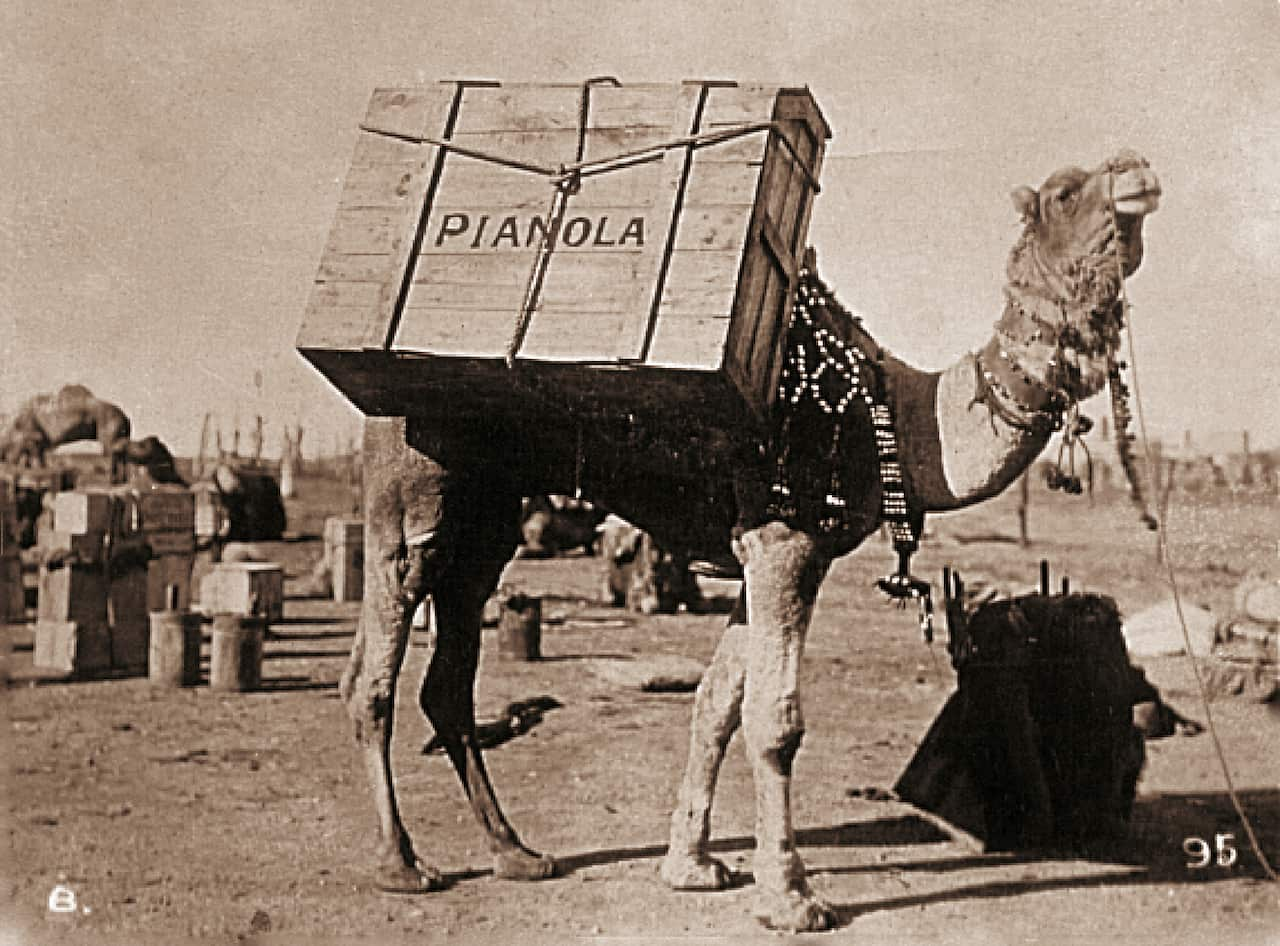

The name 'Afghan cameleer' is somewhat misleading.

It refers to a group of mostly young men who came to Australia from across the Middle East.

With their desert-hardy camels, they were instrumental in exploring land and creating infrastructure across the vast desert lands in the centre of the country.

The mosque at Broken Hill was built in 1887. It was the first in NSW, and the only one of two mosques built by cameleers remaining."

Mr Shamroze, known locally as Bobby, holds the keys to the mosque and acts as a caretaker, but doesn't worship there.

His father never passed on the religion he'd held so dearly.

“He followed the religion fairly strong,” he said.

“But he never taught me, or my brother, or my sister any of it.”

“I think they were going to knock down and sell this block, too, that’s when the Historical [Society of Broken Hill] got into it; they managed to stop them, and that’s when they rebuilt it.”

He says it was the same on his mother’s side. Her father, the mullah, was a dedicated Muslim, but the religion wasn’t taught to his children.

Documentary filmmaker Nada Roude says the White Australia policy played a role in the traditions and the religion of the cameleers fading.

“They were not able to bring their wives back, [so] many, according to history, decided to return,” she said.

“Of the remaining who stayed, history shows that they were married with the local Aboriginal community and other Europeans at the time.”

When Mr Shamroze’s grandfather died in 1960, so too, did a piece of history.

“The Council decided they’d sell the land off,” said Mr Shamroze.

“People came and bought little bits, parcels of land and there.”

“I think they were going to knock down and sell this block, too, that’s when the Historical [Society of Broken Hill] got into it; they managed to stop them, and that’s when they rebuilt it.”

Inside, the mosque holds countless pieces of the past: prayer books and traditional clothing belonging to the men; nose pegs and saddles from the camels.

But the building housing these items is, perhaps, the biggest treasure of all.

And it, said Bobby Shamroze, is slowly decaying.

Termites, water damage and the ravages of time are all taking their toll.

“The prayer room needs a new floor on it and the wall checked on one side, and the windows fixed,” he says.

“[The annex] needs the roof done, and the back wall needs doing, and round the doorway.”

“That’ll give it a bit more time. But if nothing gets done, it’s going to keep deteriorating, and the timber will just fall to pieces.”

Broken Hill's historical society lobbied to save the site from being sold off and redeveloped after the last Mullah died. The council owns the building.

“They’ve got to remember what the camel drivers have done around here."

Mayor Wincen Cuy says he would like to see the mosque preserved for future generations – but in a city filled with historic buildings, it’s not necessarily a priority.

“Broken Hill is about our history. It should be preserved,” he said.

“Exactly who is going to preserve it? We’re not quite sure at this point in time.”

Nada Roude says the building's importance extends well beyond the small community of Broken Hill.

“Muslims have always been part of Australia’s history, but a lot of it is not known or celebrated,” she said.

“I think Broken Hill is an example of the significant contribution, and the existence of a community that made a significant contribution to the development of the Australian nation.”

Now in his 70s, Bobby Shamroze is concerned about the building’s future.

He hopes the city will find a way to remember a group that helped shape a now heritage-listed city and tame some of Australia's most hostile terrain.

“They’ve got to remember what the camel drivers have done around here,” he said.

“Otherwise, this place, Broken Hill would have been behind for years.