Spring in Australia brings warmer weather, longer days, and zip ties.

That is, if you're a cyclist hoping to escape the wrath of magpies in the peak of swooping season. Each year, the black-and-white birds can become a source of suburban dread, leaving cyclists wary and pedestrians clutching umbrellas, and bringing warnings in local parks.

But Professor Darryl Jones, professor emeritus of ecology at Queensland's Griffith University, says the phenomenon is more predictable — and less sinister — than it seems.

"Magpies are stimulated by day length, which doesn't change [from year to year]," Jones told SBS News.

"They'll decide when to build nests or lay eggs depending on how long the days are."

That means breeding season follows the same rhythm every year.

The peak of swooping season falls this weekend and stretches into next week. That's when the maximum number of magpies are nesting, with eggs or chicks to protect, Jones said.

"That's why there's so much swooping … it's males protecting their nests."

The main variable is not so much the birds themselves, but how many people are moving near their nests. More human traffic means more chance of swoops.

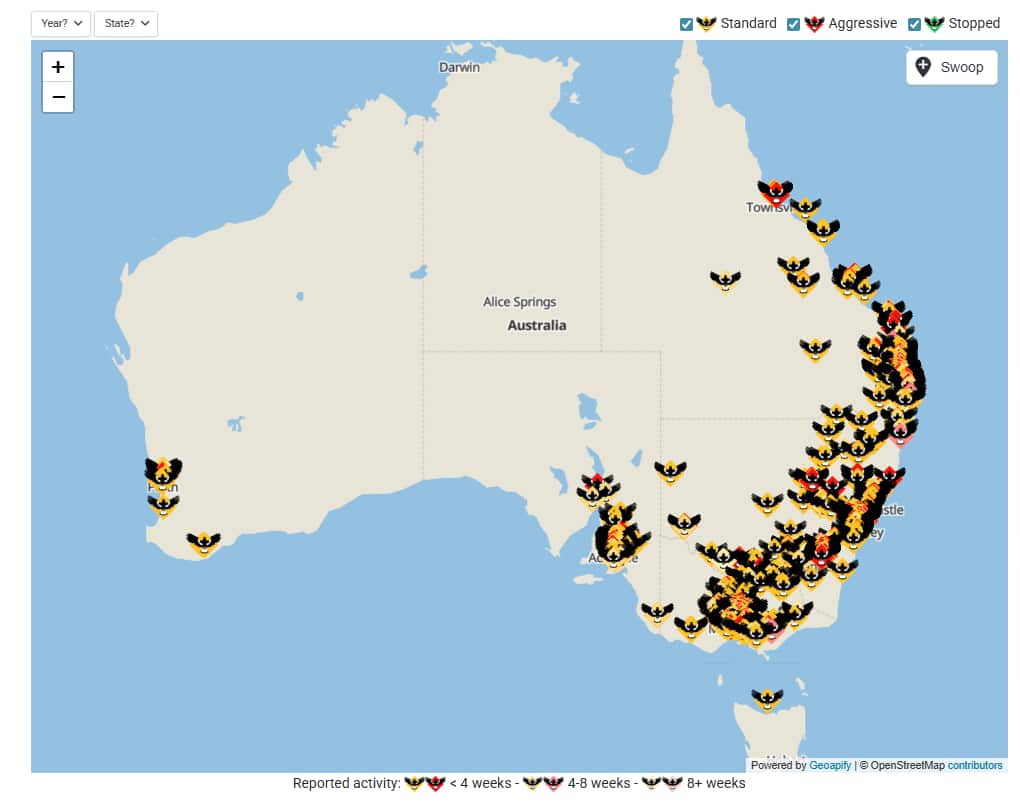

Australia's Magpie Alert map, where the public reports encounters, has already recorded 2,753 swoops and 295 injuries this year.

A misunderstood neighbour

While a magpie attack can be dangerous, Jones says Australians often misjudge the bird's behaviour. "Only about 10 per cent of magpies attack people … and it's only happening when there are babies in their nest," he said.

And even those few birds rarely attack without warning. About 100m from a nest, magpies use a distinctive call to tell people to back off. If ignored, they may fly low overhead. Only when those signals are missed do they swoop.

"We've missed all the earlier cues they've been trying to give us," Jones said. "But we don't get it. We don't understand it."

Some magpies also specialise in who they swoop. "They're either pedestrian swoopers, cyclist swoopers, or mail delivery driver swoopers," he said. Helmets can make cyclists and posties more likely targets, obscuring the face and making it harder for magpies to judge them. Men are also more likely to be attacked.

"Only a small proportion of them attack just anybody. They're the ones that get all the publicity. But they're stressed out of their scones," Jones said.

More than a bird

For many First Nations cultures, magpies are far from villains.

In Noongar Dreamtime, Koolbardi (magpie) are celebrated as the bringer of the dawn, credited with creating the first sunrise through its warble. Parrwang the magpie lifted the heavy sky that once blanketed the earth, using its warble (or a stick in its beak) to push the sky higher until light poured in.

Each morning, the magpie's song is a reminder — and a recreation — of the first dawn.

"It's proven that the magpie has one of the most complicated types of song of any bird in the world," Jones said. "There are fantastic First Nations stories about that."

"Their explanation was that every morning, magpies recreate the first dawn from their perspective. That's how strong and passionate they are about this bird."

Jones studied these stories as part of his work as an ecologist. "They have a lot of stories about magpies, but none of them were about swooping," he said. "This is a white-people-in-big-cities phenomenon."

A new friend?

Jones knows firsthand how deep the bond with magpies can go. When he was 16, he raised an orphaned magpie named Jimmy.

"I found him after a big, violent storm and knew he was going to die if I didn't look after him," he said. Jones fed him mince and raw egg until he recovered, and though he didn't want Jimmy completely tamed, the bird lost all fear of humans.

Jones was friends with Jimmy for six months, until a local bully shot him. "It had a really formative effect on me. I got really depressed for a while … but that's really where it began for me [as an ecologist]."

Magpies’ intelligence helps explain both swooping and friendship. They can recognise around 30 individual human faces and remember them for years.

Jones recalls an experiment where a student lingered near a nest and "thought bad thoughts". After five exposures, the student became an enemy of the magpies and was swooped. Years later, he returned — and was attacked instantly.

"They know all the people in their territory. They never leave the territory unless they have to. And they might live for 20 years or so," Jones says. "If those magpies see you regularly and get to know you, I think they would know you and trust you."

For some, feeding can tip the balance.

"One controversial but thoroughly examined technique is feeding," Jones says. "If your local magpie is swooping you, you can stop them by suddenly changing your behaviour. Leave out some mince or cheese and they'll quickly realise you're being good to them. Within days, they'll stop swooping and start treating you like a friend."

To truly befriend a magpie, Jones says you need to be part of that inner circle of 30 significant humans in their lives. But he understands why people might be wary.

"There’s a Jekyll and Hyde thing with magpies," Jones says. "They’re a wonderful bird that everybody seems to appreciate, but they can be terrifying if they’ve attacked you."

What to do if you're swooped by a magpie

Googly eyes on the back of your helmet won't quite cut it.

For cyclists, the safest response is to stop and walk — even if that feels counterintuitive. Spiky zip-tie helmet attachments also work. "They look dangerous to magpies, so they'll stay away," Jones said.

Other precautions include wearing a hat, carrying an umbrella, or holding a stick above your head. "But don't throw it. If you retaliate towards the magpie, it only makes them more serious," he said.

Facing the bird and backing away can also help and knowing the nest location allows you to avoid it during the few weeks of peak season.

"But remember, it's only a tiny fraction of magpies, only for about six weeks, and only near the nest tree."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.