Every morning, Reyhaneh stands in front of her wardrobe, choosing an outfit for the day — an ordinary moment for many, but for her, the start of a "daily battle".

For many Iranian women, like Reyhaneh, the choice of what to wear — and not to wear — is political.

As she prepares for the day, she is also preparing for "the resistance", bracing for potential blowback — from her "neighbour, the shopkeeper, the regime, the morality police", who all enforce Iran's mandatory hijab rules.

She then leaves the house without a headscarf, a main part of the country's strict dress code, which also requires women to wear loose clothing and keep their arms and legs covered and men to wear long trousers.

"[The headscarf] is just an excuse for many other restrictions … It is not just the two or three metres of cloth you put on your head," Reyhaneh tells SBS News.

"This has now become the best outward symbol of expressing our opposition [to the situation in Iran], which is why I still prefer to go out without the hijab."

SBS News has changed Reyhaneh's name for security reasons.

She first decided to flout hijab rules three years ago, when her headscarf slipped off as she was walking home, and she chose not to pull it back on.

"It was as if someone whispered in my ear, 'No, put it on,' and the other one said, 'No, don't put it on,'" Reyhaneh recalls.

"It was a strange feeling, like a strange fear … It was like someone had a gun to your head and wanted to shoot.

Fortunately, the voice telling me not to put it on seemed stronger and louder than the other.

The moment came at the peak of the "Woman, Life, Freedom" movement — a series of protests in Iran sparked by the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini in September 2022.

Amini, who was from Iran's Kurdish minority, was arrested by Iran's Guidance Patrol — colloquially known as the 'morality police' — for allegedly not observing the country's mandatory hijab laws.

Her death led to nationwide protests and sparked a resistance movement that continues today.

"She was not a person that everyone knew … But this girl, who was little-known, had such a huge impact on the whole of society that it was really hard to imagine," Reyhaneh says.

"It seemed like this girl's death, because of the hijab, became an excuse for us to wake up and take a bigger step forward."

Rising up against the regime

From Amini's birthplace in Iran's Kurdistan province to the Kasra Hospital in Tehran where she died, thousands took to the streets chanting "Zan, Zendegi, Azadi" — meaning "Woman, Life, Freedom" — and demanding regime change.

Shahrzad Orang, an Iranian woman currently living in Australia, was one of the protesters who gathered in front of Kasra Hospital, "finding their freedom in the street".

"I just thought that she could be my sister or one of my close friends … it's my duty to join protest," she tells SBS News.

"We cried, we go to street to say … 'the way that you [the regime] are acting to us, it's not correct.'"

The movement spread widely across Iran, with hundreds of thousands marching in almost 80 cities and demonstrating in various ways, including burning headscarves.

"I was in the middle of the street and I could see women who [were] wearing hijab. So I went to ask them … and they accepted, they gave their headscarves," Orang says.

"It was like 70, 75 headscarves that I burned at the same time."

The protests were met with force by the Iranian regime, with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei describing the Woman, Life, Freedom movement as a "hybrid war".

The Human Rights Activists News Agency reported in April 2023 that state security forces killed at least 537 people during the protests, while more than 19,000 were arrested.

Regime officials have denied these figures, claiming 202 people were killed during the uprising "by the rioters" or after attacking police bases and personnel.

Orang says two of her friends died during the movement, and five others are still in prison.

"The violence level was really high … We didn't have anything in our hands, [not] even a stone," she says.

[The security forces] had many things like batons, guns, and they shot at us when we were in the middle of the streets. It was an unfair war.

Orang says her hand was broken when she was hit by a baton during a protest in west Tehran.

Later on, she was arrested by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a branch of the Iranian armed forces, and held for about 36 hours.

"They checked the phones and calls, and emails, everything on my phone," she says.

"They told me that 'you are gonna die. You are not going to leave. And it's not that much longer for you to be healthy, and we are gonna kill you'.''

After the arrest and threats, Orang fled to Australia in February 2023, just one week before she received a travel ban and a court ruling.

"I just felt that maybe it's better to leave Iran because I had many threats every day … I had to change my location every day," she says.

"I'm worried about my family [who are still in Iran], but I'm worried for my people as well.

"I think that I'm on the right side of history, and I'm going to do what I did before and continue till we get our freedom."

'An act of resistance'

While the street protests have subsided, women in Iran are still resisting in various ways, including by 'dejabbing' (removing the hijab).

In 2023, a survey by Iran Open Data (IOD), an independent organisation that makes Iranian government data transparent and accessible, revealed that 86 per cent of women had appeared in public without the mandatory hijab.

Shadi Rouhshahbaz, an Iranian Australian activist and researcher, says the resistance movement "has changed drastically" in the past three years.

"I think being alive and continuing to live under the Islamic Republic is an act of resistance," Rouhshahbaz says.

"I'm seeing women going towards basic acts of civil disobedience … engaging a lot through social media, doing social media campaigns on a variety of issues that focus on reclaiming their rights.

"But also across the whole system, with regard to financial empowerment, [for example] running women-led businesses and using whatever they can through their financial independence to create businesses and activities that generate income."

There have also been reports and social media videos showing Iranian women dancing and singing in the streets, defying the country's public singing rules for women.

But these acts of defiance have also triggered backlash from authorities.

In 2023, five young Iranian women were arrested after posting a video of themselves dancing to a popular song on TikTok.

Last year, Iranian singer Parastoo Ahmadi was arrested after she held an 'imaginary concert' and performed without a headscarf for an online audience. The Iranian judiciary announced the arrest, saying Ahmadi had not adhered to "legal and religious norms".

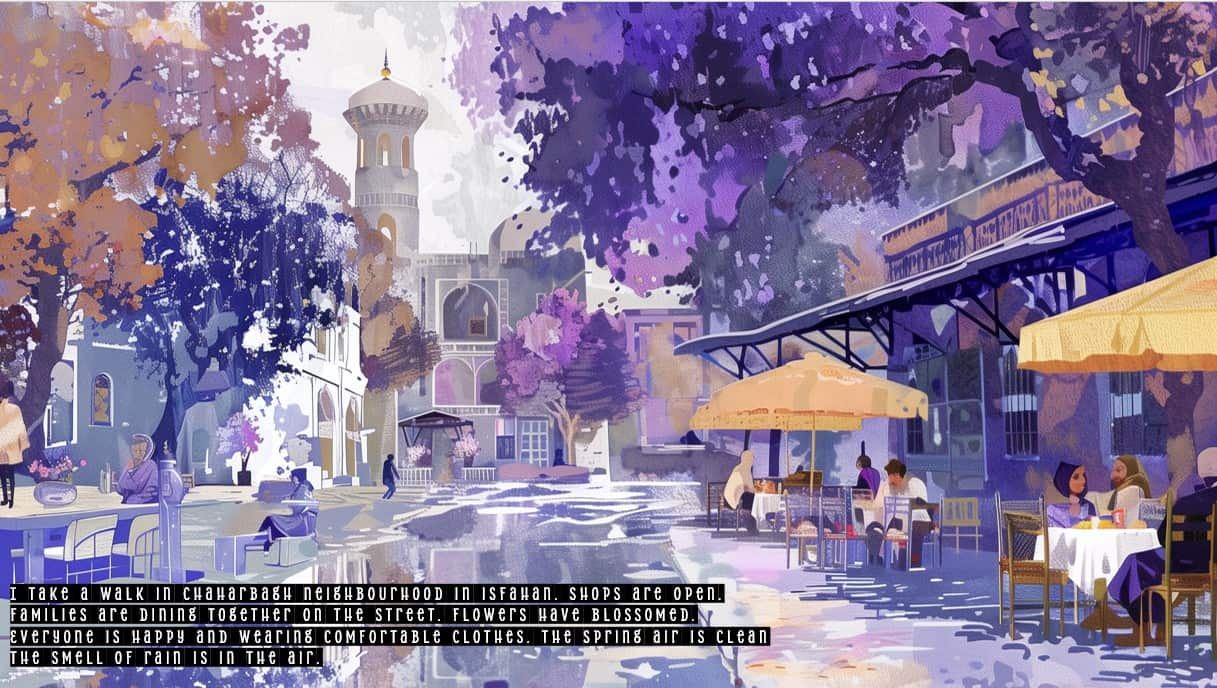

"An ordinary life is something that Iranian women, and I'm sure many of the women around the world, are aspiring to have," Rouhshahbaz says.

"Ordinary acts of life — like singing, like dancing — I think that's another [example] of how we see women stepping up."

Digital crackdown, digital resistance

Just as the resistance movement is evolving, the regime is also finding new ways to repress women using digital tools.

This includes its deployment of surveillance measures and the roll-out of a state-backed mobile app encouraging citizens to report women for breaching hijab laws.

Dara Conduit, a lecturer in political science at the University of Melbourne, says: "The regime is trying to find ways to control the hijab."

"It's a really challenging thing for the regime to control, because you can see when they control it the way they did with Mahsa Amini, it led to protests."

In 2023, the Iranian Fars News Agency released a video claiming police are using 'smart cameras', or artificial intelligence-powered cameras, which can identify those who are not wearing hijab through facial recognition technology.

There have also been reports of women receiving text messages with warnings of reprisal for violating hijab laws.

"That would be a really powerful tool because it would mean that the regime can actually police this without getting into confrontations with young women on the street," Conduit says.

"Whether they can actually do this or not is another story, but that is what the regime is claiming that it is trying to do.

I think that in itself is important because that creates fear.

In March this year, findings from the United Nations' Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran also showed that the regime had "resorted to aerial drone surveillance to monitor hijab compliance in public spaces" in Tehran and southern Iran. It also noted that facial recognition software had been reportedly installed at the entrance of a university in Tehran to monitor female students.

Across Iran, police have introduced a mobile app that enables officers and other vetted individuals to flag women for not complying with hijab rules on public transport, in private vehicles and on social media.

Fighting back against 'deeply patriarchal views'

But Iranian women are also using digital tools to fight back — for example, reporting harassment via the women-led online collective 'Harasswatch'.

According to its editor in chief, Ghoncheh Ghavami, the platform was founded in 2018, "to focus on sexual harassment in public spaces, a pervasive, often trivialised form of violence that had been overlooked as a serious issue", and to "engage and mobilise people across different social classes, genders, and backgrounds".

Ghavami tells SBS News: "We recognised it [harassment] instead as a fundamental form of oppression and identified it as a critical area that until then had not been addressed in a systematic way by any feminist, collective or organisation.

"We defined our mission as challenging the normalisation of sexual harassment, breaking the culture of shame and silence around it."

A few months after the platform was established, the group expanded its activities by distributing educational leaflets about "street harassment", inspired by the work of anti-harassment graphic artists during the 2011 Egyptian revolution.

Ghavami says while distributing the flyers, they often had to "engage with men who held deeply patriarchal views".

"We always had to emphasise that sexual harassment is about power and a sense of entitlement, not sexual desire … and it has nothing to do with what they [women] wear," she says.

"The issue of compulsory hijab is deeply intertwined with sexual violence.

Mandating hijab, along with the propaganda and punishment surrounding it, has contributed to the normalisation of sexual violence in Iran.

Harasswatch also faced allegations from regime officials during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, with the Iranian Judiciary's news outlet claiming the platform had "managed to create the grounds of a major riot in Iran through networking".

Ghavami says after the movement started, Harasswatch's activities "expanded significantly".

"Every day, I received various reports from prisons, detention centres, street protests, state-sanctioned sexual violence against protesting women, the daily struggle of women against mandatory hijab, and more," she says.

"Feminist activists were repeatedly arrested in different parts of the country, and information about them was published on Harasswatch."

Resisting 'day after day'

Survey data from IOD shows that 70 per cent of Iranian women reported feeling concerned when they went out in public without a hijab.

Reyhaneh says: "I'm ready to be arrested for [not wearing] hijab or get a text message saying I'm not wearing hijab.

This fear still exists, not from ordinary people, but from the government's response … [we believe] going out without the hijab day after day, can add a page to our [judicial] case.

Even still, women like Reyhaneh continue their daily battle, dreaming of a future where their demands for equality and regime change are met.

"It's true that I go out without a headscarf, but I still can't wear the clothes I like on the street," she says.

"I still have my headscarves.

"Even if the regime falls, I think I'll keep one or two of them as a symbol of the era we had to endure; as a souvenir of the era we endured because of this scarf."

This story was produced in collaboration with SBS Persian.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.