Advocacy group Human Rights Watch has released a report which has found that children working on tobacco farms in Indonesia are suffering from adverse medical effects related to their jobs.

The group has accused the Indonesian government of doing little to educate families about the dangers, especially in poorer communities where farming work is often part of a rural upbringing.

Two large multinationals operating there - Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco - market their products in Australia.

Indonesia is the world's fifth-largest tobacco producer, with more than half a million farms. An estimated 1.5 million children work in agriculture there, but there are no concrete figures on the proportion who work with tobacco growing.

An estimated 1.5 million children work in agriculture there, but there are no concrete figures on the proportion who work with tobacco growing.

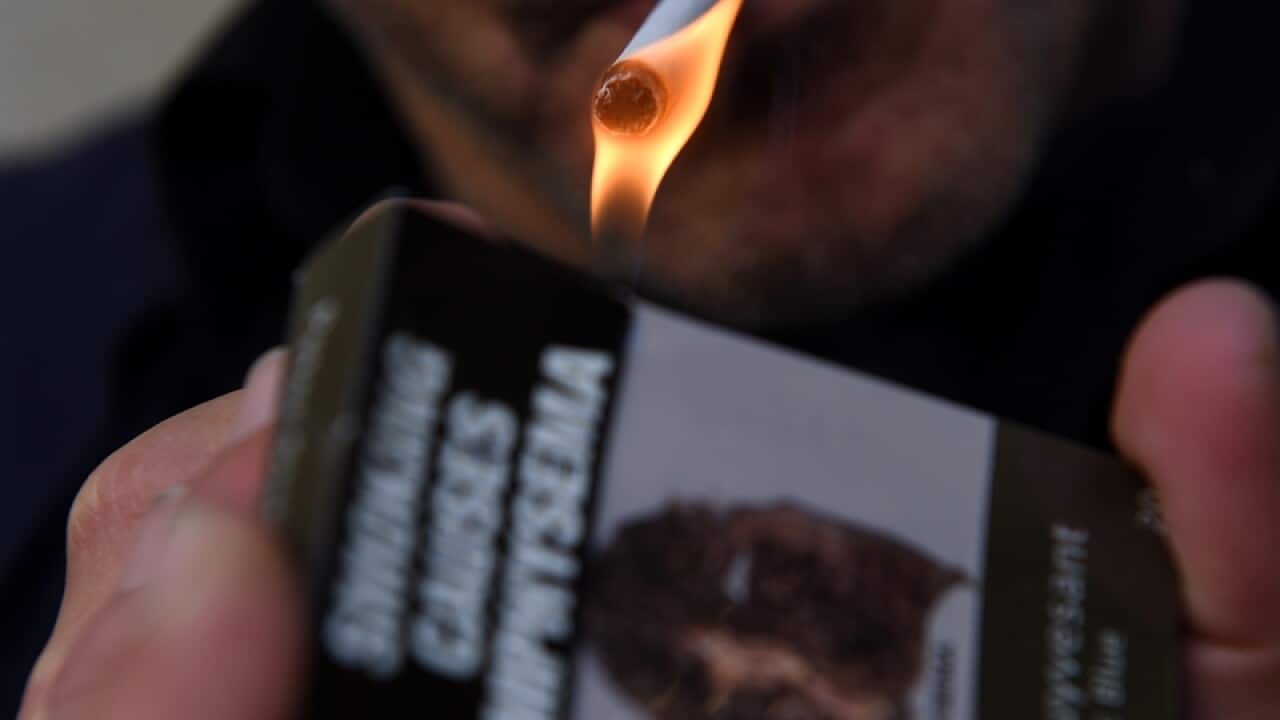

Children working on tobacco farms in Indonesia (Human Rights Watch) Source: Human Rights Watch

On farms in East Java, some children reportedly earn about 10 to 15,000 rupiah - little more than one Australian dollar - for a seven-hour work day, when they sow seeds.

One 11-year-old boy said the hardest part was watering the plants with a kettle he carries from home, because he has to draw water from the well, and manage the weight as he waters.

“The plant is a little taller than me,” he said, pointing above his head.

One adult worker said it's part of life.

“Here, every child touches tobacco leaves,” she said.

“During tobacco season, every child has to help after school.”

More reading

Tobacco giant loses case against Aust govt

Nicotine permeates through skin.

Half the children interviewed in the Human Rights Watch report described symptoms consistent with acute nicotine poisoning.

A 12-year-old girl from Sampang described working the fields with her father.

“After watering, I felt nauseous because of the smell of the tobacco," she said

"Then I vomited in the fields and my dad told me to go home to rest. I was sick for two days."

The group researcher Margaret Wurth, who authored the report, said such conditions were unacceptable.

“Children just should not be doing hazardous work where they're handling tobacco that could have affect their health,” she said.

“The problem here is that, you know, among the families we interviewed, very few of them have ever received any kind of meaningful education about what the hazards of the work could be for their kids, so they didn't know.

"That's why it's essential that companies and the government get this information to families so they can protect their kids.”

Aside from the nicotine, there are also pesticides.

Some of the children interviewed said they didn’t even have gloves, and one boy described tying his own vest around his face for a mask as he sprayed.

Several of them said they ended up in hospital for days at a time.

Children take part in cultivation, harvesting and processing of the leaves, including rolling them for drying, and sorting the chopped product.

Once the leaves are dried, cut and sold on the open market, there's no real way to track where it was produced, or under what conditions.

Even the farmers admit there’s little monitoring of the supply chain.

“When I send to the storehouse, it only depends on the quality of tobacco I send them,” Suradi, a farmer and trader, said.

More reading

Tobacco company 'furious" at treasurer

“They don't ask if I employ small children, or if they help their parents, or who's chopping the tobacco leaves, or working for me.”

The largest companies operating in Indonesia include two owned by multinational giants British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International.

British American Tobacco told SBS it doesn't employ children in any of its operations, and says it’s working with groups in Indonesia to tackle exploitative child labour.

Philip Morris International said it welcomed the report, but pointed out that reform of the industry won't happen overnight.

It said changing practices requires the participation of the Indonesian stakeholders, but in the meantime, they’ve tried to move towards a more transparent supply chain.

“The critical step we have taken in Indonesia, is to move away from the so-called open market, and today we're sourcing already 70 per cent of our volumes through direct contracts with farmers,” said Miguel Coleta, Philip Morris International’s sustainability officer.

He said four years ago, that proportion was just 10 percent.

But in Indonesia’s tobacco farming villages, researchers say, if things are to change, education must start at home.

Share