Mohsin's life in Iraq was 'destroyed' by the US invasion. When he fled to Australia, tragedy struck

On 19 March 2003, the US announced its invasion of Iraq despite huge anti-war protests around the world. One man who fled Iraq for Australia says the memories still haunt him to this day.

Published

KEY POINTS:

- 19 March 2023 marks 20 years since the US invaded Iraq.

- Some Iraqis hoped things would quickly return to normal after President Saddam Hussein was ousted. But they didn't.

- The invasion spiralled into a war that would last until 2011.

Two decades after the United States launched its invasion of Iraq, Mohsin* said the memories still bring him "overwhelming pain".

"What happened in 2003, I don't want happening anywhere in the world - not just Iraq, anywhere," he said.

To this day, Mohsin, 46, who fled Iraq and found refuge in Australia, said he still doesn't understand what happened to his country.

But he doesn't place blame solely on Iraq's former president, Saddam Hussein, despite him being an "extremely harsh ruler".

"Who's to blame? Just Saddam? No, the US is also to blame. It wasn't just Saddam who we should blame - the US treated us the same way," he said.

Mohsin fled his home country 18 years ago as the war raged, feeling he had no choice but to leave because life was not getting better despite US forces ousting Mr Hussein.

"[The US] said they were going to come and fix the country, but it turns out, no. Rebel groups and the US military were killing people, they were shooting people. Anybody who approached them risked being killed," he said.

Sunday 19 March 2023 marks 20 years since US president George W. Bush announced the US-led invasion, which spiralled into a war that lasted until 2011.

Mohsin believed life would return to normal after a couple of months, but that was not the case.

"By 2005, it was destroyed. Sectarianism conflict broke out... there was nothing left for us there. How was I going to benefit from this country? This is the point where I knew I had to leave," he said.

The next year, Mohsin and his family escaped to Malaysia before travelling to Indonesia.

They came to Australia by boat in 2010 after he was granted a temporary protection visa, but it was a tragic journey.

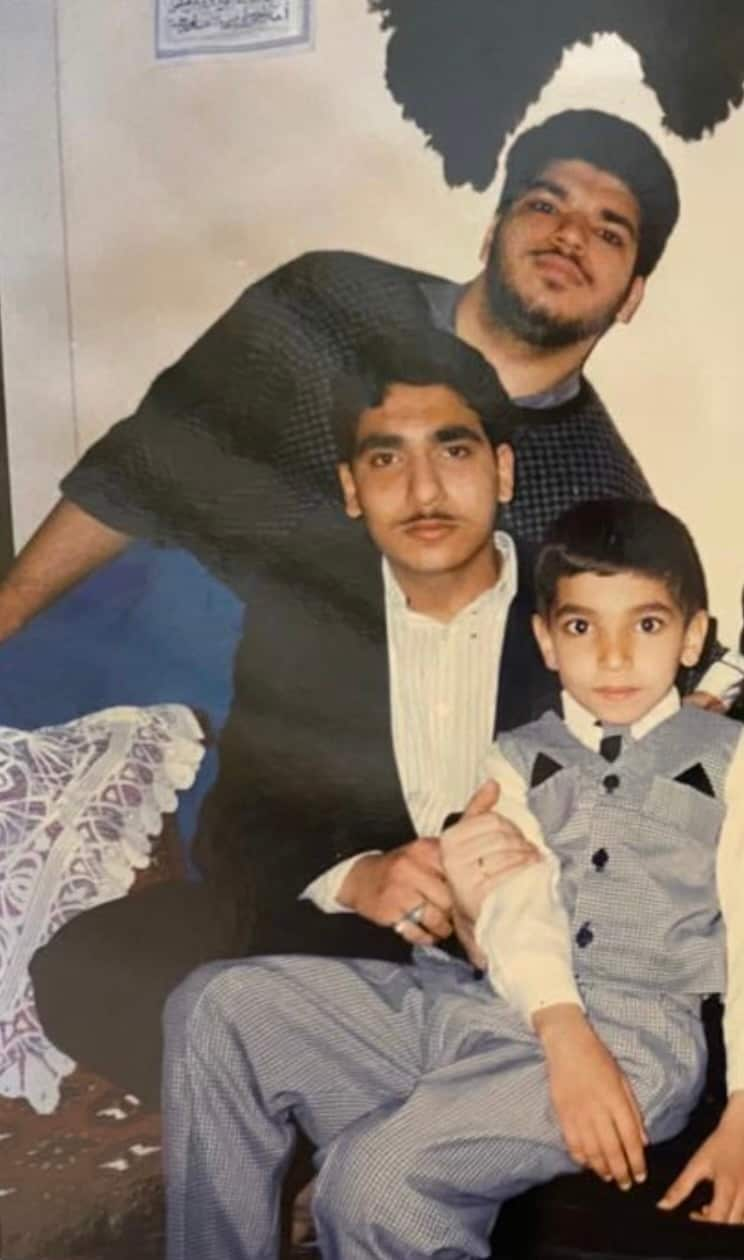

On the way to Christmas Island disaster struck, and 91 of the 131 people on board drowned, including his three young children.

"I try to forget the experience that I had ... If Iraq improved by a million times today, it would still not be good enough and I will never return there. All I can think about is the experience that I had. And I don't want to remember it," he said.

What sparked the invasion?

The US-led war came against the backdrop of heightened terrorism fears, according to Benjamin Isakhan, a professor of international politics at Deakin University.

Eighteen months earlier the US had been rocked by the September 11 terror attacks in New York City.

"The real fear in the US at that time was that a state like Iraq might have weapons of mass destruction and that it might be harbouring terrorists," Professor Isakhan said.

Prior to announcing the invasion, Mr Bush claimed that US intelligence had found that Iraq had "some of the most lethal weapons ever devised", and that it "harboured terrorists, including operatives of al-Qaeda" — who had coordinated the September 11 attacks.

When the official call had been made, Australia's then-prime minister John Howard backed the US president and committed troops to join the fight. He said it was in Australia's national interest to "deprive Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction".

But in the early months of the war, it emerged that the intelligence suggesting Iraq had weapons of mass destruction was not as solid as had been claimed.

David Kay, then-head of the CIA's Iraq Survey Group (ISG), said in October 2003 that no weapons of this type had been discovered.

A year later, the ISG delivered a report to the US Congress following a 15-month search involving 1,200 of its inspectors who had searched sites across Iraq. No weapons of mass destruction had been found, and the ISG concluded that Mr Hussein destroyed the last of them a decade earlier.

It said Mr Hussein had ambitions to restart chemical and nuclear programs once sanctions were lifted. But because there were no recent signs of discussion or interest in establishing a new biological warfare (BW) program, Iraq would "have faced great difficult in re-establishing an effective BW agent production capability".

Claims Mr Hussein had formal links with al-Qaeda, which were used as justification for the invasion, were also being questioned. In 2006, a declassified US Senate report revealed there was no evidence of this.

'Who could feel happy about a foreign flag being flown in their homeland?'

Basim Alansari was already an Iraqi refugee as he watched his country crumble on live television at his student accommodation in a regional NSW university.

Mr Alansari was only nine years old when he escaped the 1990 Gulf War — sparked by Iraq's invasion of neighbouring Kuwait — with his family, and finally came to Australia by boat when he was 17.

He felt giddy with excitement after watching US troops drape an American flag over a statue of Mr Hussein.

"I remember calling my dad and I go Saddam is gone!," he said.

He was met with heavy weeping by his father, who had narrowly escaped death row under Mr Hussein's rule.

When Basim thought his dad's unusual crying was due to happiness, he said his dad screamed at him.

"Who could see a foreign flag being flown in their own homeland, and feel happy in such a moment?" Mr Alansari recalls his dad saying.

Mr Hussein went into hiding after US troops seized the capital, Baghdad, less than a month into the invasion. He was captured in December 2003, and executed three years later after being convicted of crimes against humanity by the Iraqi Special Tribunal.

After his overthrow, which ended a brutal 24-year rule, more violence followed.

Al-Qaeda's leader in Iraq, Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, who was killed by US forces in 2006, started waging bloody attacks designed to turn majority Shi’ite Muslims against minority Sunnis in a civil war. It eventually transpired and engulfed Iraq from 2006 to 2008.

Huge protests in Australia and around the world

As it became increasingly apparent that the US would invade Iraq, millions of people took to the streets calling for a peaceful solution.

Between six and 10 million people demonstrated across the world on 15 and 16 February, 2003, according to a BBC report at the time. Some have labelled it the largest single coordinated protest in history, with the Guinness World Records recognising Italy as having the biggest anti-war turnout at three million people.

Mohammad Awad was among the hundreds of thousands of people who rallied across Australia that weekend.

Mr Awad remembers heading out with his family to stores in Bankstown, western Sydney, where they bought markers, paint, and glitter to design posters.

He recalled his parents explaining that they were going to the demonstration because what was happening was "unfair".

"It was our first education on imperialism and everything going on in the Middle East; why American intervention never works, all that sort of stuff," Mr Awad, now 23, said.

"I remember [chanting], 'John Howard is a coward'.

"I had never been to a protest before, I had never seen such a big demonstration of people before."

Many prominent Australians were also vocal in their opposition to the war, with the late Heath Ledger joining fellow actors Joel Edgerton, Naomi Watts, and thousands of others at a rally in Melbourne after the invasion was announced.

And in January of that year, Toni Collette and Judy Davis were among anti-war activists who attempted to present Mr Howard with an application for US citizenship because he had aligned Australia with Washington's hardline stance against Iraq.

"He’s blindly following Bush, like a sheep, into a pit and who knows what the repercussions may be,″ Collette said at the time.

The war's toll

In 2008, Mr Bush agreed to withdraw US troops from Iraq, a process that was completed under President Barack Obama in 2011 — the same year Britain's remaining forces left.

Australia ended its operations in 2009.

The number of civilians that died during the war is difficult to ascertain. In 2009, three years before the war ended, the Associated Press reported 110,600 Iraqis had been killed.

When announcing the invasion, Mr Bush said the US would help "build new Iraq that is prosperous and free".

Professor Isakhan said that promise had not yet been fulfilled, and given Australia was a participant, the government should do more to ensure it is.

He said "simple things" like providing exchange and scholarship programs for Iraqi students would go some way in helping achieve this.

Professor Isakhan believes the West has learned "a lot of hard lessons" in the wake of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

"You can't go into these very complex and conflict-ridden societies and fix them in five years and turn them into robust democracies in 10 or 20 years," he said.

"There is no simple fix, and I think that's really a big problem for foreign policy at the moment... because staying away is a problem, and going in is a problem."

*Name has been changed.

SBS World News