"Everything changed" for Mike Sadler in 2020, when the payment he received from Centrelink increased by $550 a fortnight.

The supplemental payment, introduced in recognition of the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on the Australian workforce, was applied on top of his JobSeeker payment.

All of a sudden, his fortnightly income was $1,115.70 — brought above the poverty line, closer to the national median wage.

It was a relief. Before the increase, Mike and his family of four had been eating a lot of "brown food", he said.

"It was cheaper to buy packaged chips than potatoes, so we'd buy the packets," he told SBS News.

"But suddenly it was COVID and the payments went up and we could afford the potatoes, afford fresh produce."

For Australians like Mike, the end of the Coronavirus Supplement in 2021 and the return to "regular" social support payments like JobSeeker, Austudy and Youth Allowance after lockdown meant a return to poverty.

Advocates are calling for government service payments to be brought back up to COVID-levels, to address the millions of Australian students, jobseekers and single parents who are forced to live below the income poverty line as rents steadily increase nationally.

In spite of small increases to social support payments since the pandemic, including a $12.50 per fortnight increase to JobSeeker in September this year, Australia's social service payments are "woefully" below the poverty line, the head of a leading anti-poverty advocacy group says.

One in seven Australians living below the poverty line

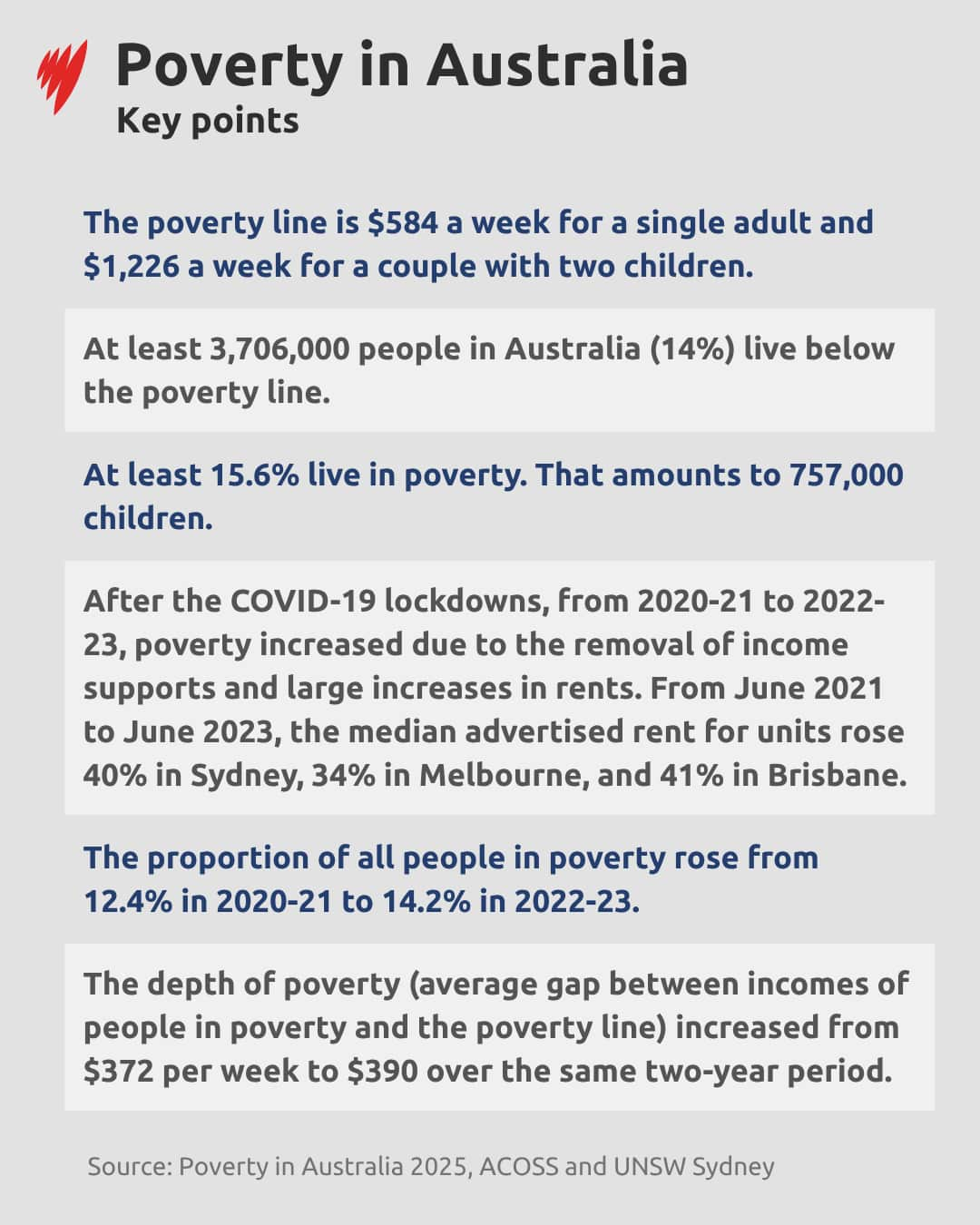

A new report from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and the national advocacy group for poverty, disadvantage and inequality, the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS), found more than 3 million Australians were living below the poverty line in 2022-23.

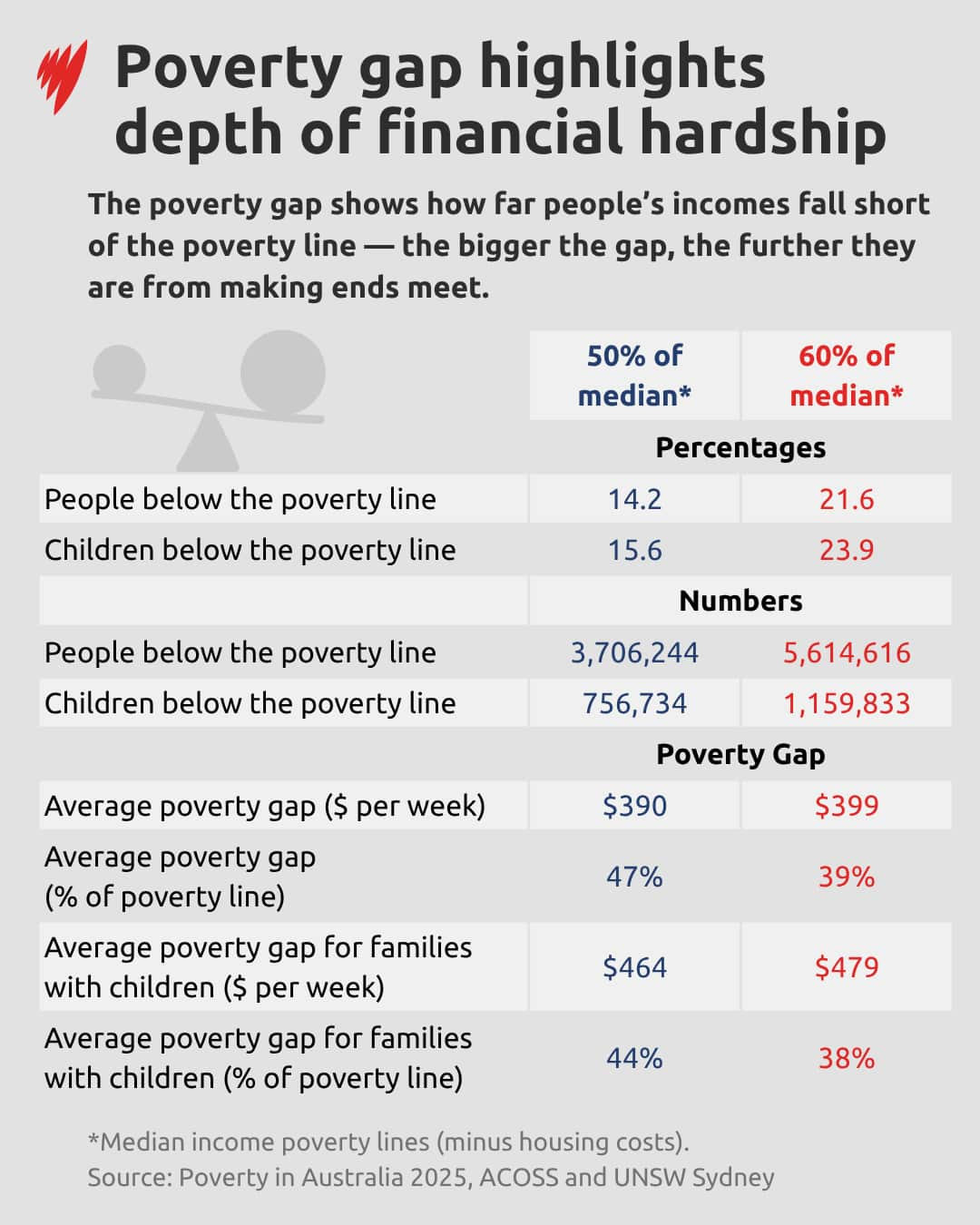

The relative poverty line is defined as 50 per cent of the median household after-tax income, with those below it considered to be experiencing poverty.

Using the latest figures from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, researchers found the number of people living in poverty in Australia has increased to one in seven, up from one in eight in 2020-21.

Speaking at a press conference in Canberra, ACOSS CEO Cassandra Goldie said an increasing number of Australians were faced with the choice between putting food on the table and experiencing homelessness.

"The reality is that in one of the wealthiest countries in the world, poverty is on the rise. Housing costs are affecting many people, but if you're on a low fixed income, JobSeeker is just $401 a week," she said.

Yuvisthi Naidoo, a senior research fellow at UNSW's Social Policy Research Centre said the JobSeeker payment was just 42 per cent of the national minimum wage.

"In our report, we show how far the income support payments are below the poverty line," she told SBS News.

"Currently, for example, somebody who is relying on the JobSeeker payment is $205 per week below the income poverty line. A sole parent with two children who is on a family payment is $163 below the poverty line. And a young person on Youth Allowance is $279 under the poverty line."

The report found the poverty line for a single adult is $584 per week, minus housing costs. JobSeeker is now $793.60 per fortnight for a single with no dependants, while a single person with one or more children receives a maximum of $849.90.

The figures reveal a poverty gap of more than $200 per week, for a single with no dependants. For families with children, the poverty line was $1,226, meaning incomes on that weekly payment were nearly $300 below the poverty line each week.

Naidoo said indexation increases, such as that made in September, make little difference when the poverty gap — the difference between current payments and the poverty line — is already so wide.

"When we talk about what the poverty line is, we remember the national minimum wage is a figure that's higher than the poverty line. The JobSeeker payments are so far below the line and level of destitution."

Naidoo said it was "not possible to live on income support payments", even if a recipient also receives rent assistance.

Families with children

Mike and his wife Liz moved to Wagga Wagga from Sydney with their two young children after finding themselves out of work and unable to afford rent.

The pair decided to study and become primary school teachers — something they thought would be an "absolute job-guarantee way of retraining".

"But you've basically got to live on Austudy, in poverty for four or five years, and then you're going to have debt at the end of it," Mike said.

"It was a matter of searching for food almost to see what you could afford to put on the table before the money ran out each fortnight."

ACOSS' report stresses that one in six children is living below the poverty line — more than 750,000 Australian kids. Goldie said it was "disturbing" for everyone.

"What's disturbing for all of us is that we are seeing an increase in poverty on our watch," she said.

"I think it's very true that in a very wealthy country, for many people, [living in poverty] is a devastating experience that leads to a great sense of 'I'm not as worthy as other people' and a great desire to hide the experience, as you look around and see other people who have a lot of money, and a lot of people who are doing extremely well."

She said for children in particular it was a "terrible signal".

And for parents, Goldie said poverty had "devastating effects".

"Both in the immediate term in terms of chronic anxiety and distress — you're constantly figuring 'What can I afford today, what can I go without, do I keep paying the rent and keep the roof over my head whilst I can only afford to feed myself once a day?"

She said experiencing poverty had significant impacts on people's mental health, and would leave acute anxiety, something Mike says he is all too familiar with.

"It'd often come down to the last five dollars, for Liz and I to not eat, to feed the kids," he said.

"It is a juggling act of the highest order, trying to juggle all this stuff and at the end you still fail, right? It just depends how well you do it, and you kick yourself when you fail, but it's how well you can juggle all of this stuff."

Mike said the worst part of poverty was the social isolation.

"When you're living on Centrelink income support, the kids and yourself are basically prevented from going anywhere," he said.

"You've got no money to put petrol in the car, so you don't go visiting, you can't meet friends at the pub for a pizza, right? It's just not something you can do at all."

Cost of living pressures, housing stress key drivers of poverty

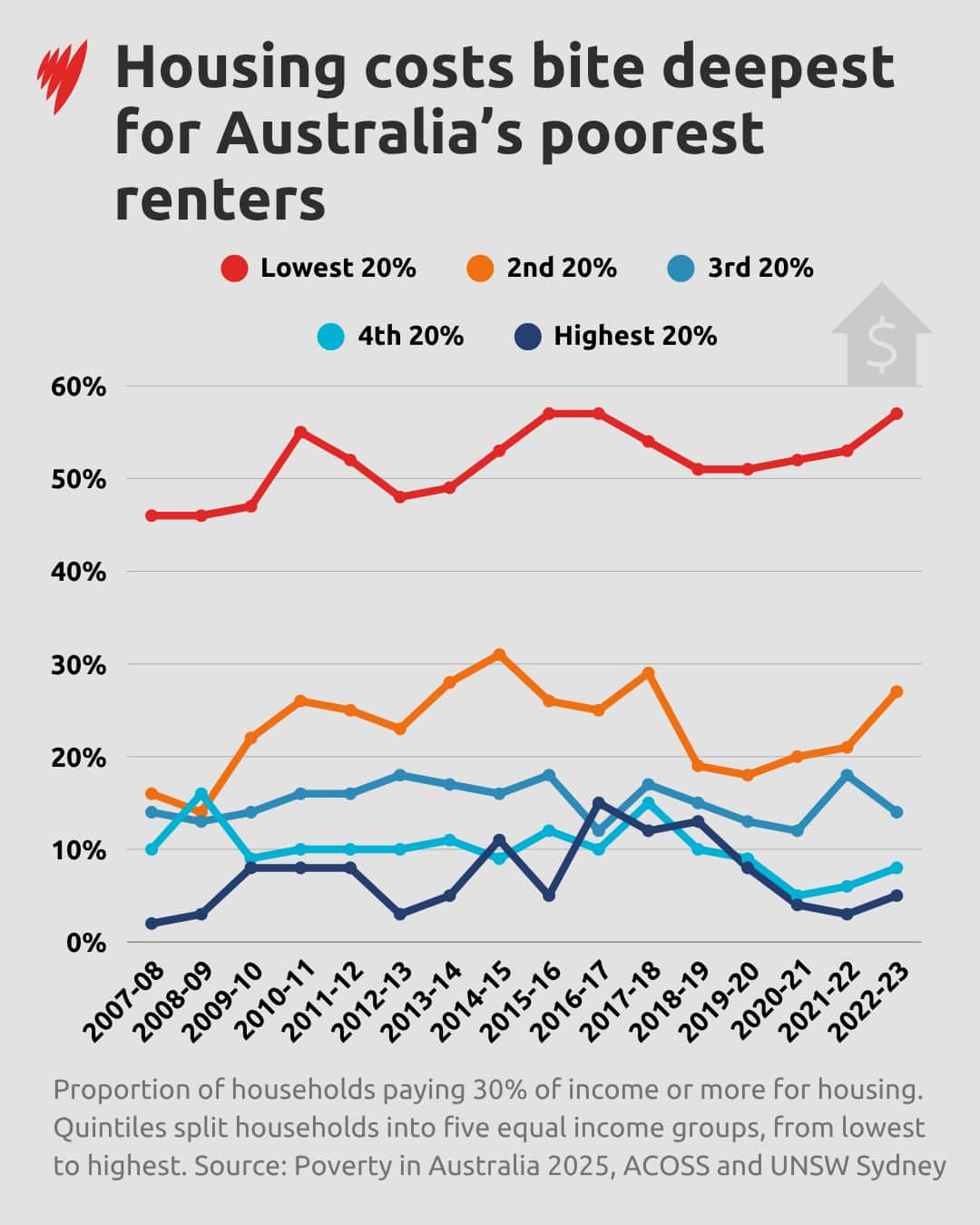

The report highlights increasing rents as a key driver of rising poverty. Housing affordability advocates agree.

Kate Colvin, a spokesperson for Everybody's Home, a national advocacy coalition targeting Australia's housing crisis, said the poverty report "demonstrates that runaway rents are pushing more Australians than ever into rental stress and homelessness, leaving many struggling to cover basic living costs".

“No one should have to choose between paying rent and buying food, medicine and other essentials, but sadly this is becoming more common," she told SBS News.

The report notes that the lowest-paid people were experiencing rental stress — when more than 30 per cent of one's pay is spent on rent.

In the 2022-2023 period, the proportion of renters in the lowest 20 per cent of earners experiencing rental stress increased to 57 per cent, up from 52 per cent in 2020–21.

"Access to a safe, decent, and affordable home is the foundation to building a stable, secure life," Colvin said.

"Right now, Australia has a social housing shortfall of 640,000 homes and demand is rising.

"To turn the tide on rising poverty we need the federal government to urgently deliver a major boost to public and community housing so people being squeezed out of the rental market can find a decent, affordable home."

Naidoo said rent assistance wasn't helping low-income earners.

She said from 2021 to 2023, median advertised rents for units went up 30 to 40 per cent in all major cities.

The federal government increased rent assistance by 10 per cent in September 2024, but Naidoo said it needs to be "significantly higher".

"The important thing to remember is that only around a quarter of all people on income support payments actually receive Commonwealth rent assistance," she said.

Mike said he believes that everyone just wants to work.

"It's a social thing. It's an empowering thing. It gives you some satisfaction," he said.

He said he didn't think people really understood the "social exclusion that comes with having no money".

"You just cannot participate in society, and when that happens, communities break down," he said.

"But please, people shouldn't be treating those who don't have those resources like pariahs. All us humans need this. It's part of who we are, and to have it excluded as a kind of punishment defies logic to me."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.