When Hira Hona decided to tattoo half his face, he didn't even think to ask his employer for permission. It simply wasn't necessary.

The 35-year-old is the principal of a Māori immersion primary school in Tauranga — on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island — where the centuries-old practice of facial tattoos is deeply understood and accepted.

"We're in a new world," Hona tells SBS News.

"It would go against every principle, every value of our kura, of our school, if they were to question it."

His experience is a marked departure from that of his parents and grandparents, who grew up at a time when the practice was far less accepted — and when Māori culture itself was often suppressed in schools rather than celebrated.

Hona says he and his wife spent three years having "hard conversations" about whether they were ready to receive facial tattoos — a sacred practice for Māori. When they finally did, in an intimate ceremony, "it was almost like another marriage".

"When you rise up again into your mataora, you're reborn," he says.

Mataora is the name given to facial tattoos worn by Māori men, which can cover half or all of the face. Māori women receive moko kauae, a distinctive marking on the chin that can extend to the lips.

Māori tattoos, or tā moko, are typically drawn freehand by an artist in consultation with the recipient, who will incorporate the recipient's ancestry and story into the design.

Tā moko have become increasingly visible since the late 1980s, along with other expressions of Māori culture and language, following years of cultural suppression under colonisation.

Today, many Māori view moko as a way to embrace and express identity and reclaim culture – and, for some, as a symbol of resistance against a government accused of pushing policies that erode Māori culture and rights.

"It's a reminder to the government that we're still here. You can throw stones. You can throw all you want at us, but at the end of the day, you can't get rid of us," Hona says.

A sacred art suppressed

For centuries before European settlement, Māori in New Zealand were telling stories, marking milestones and accomplishments, and representing their whakapapa (genealogy) through intricate tā moko etched on their faces and bodies using uhi chisels and natural inks.

Ngarino Ellis, a Māori art historian and professor at the University of Auckland, explains: "Different people in our communities would receive it in different places to mark different events.

"Sometimes if a warrior outdid themselves, then they would be gifted a moko when they came back to the pā (village), on their buttocks and on their thighs.

It was just seen as normal, as part of just who you were.

When European settlers began arriving en masse in the early 19th century, Māori culture was forced to adapt, Ellis says.

"Our culture changed more rapidly to try and mediate increasing encroachment into our sovereignty."

In 1907, the Tohunga Suppression Act targeted Māori spiritual, healing and cultural experts, further marginalising traditional knowledge and practices such as tā moko.

Over the following decades, a range of assimilation measures continued to erode Māori cultural forms. In schools, Māori children were discouraged from and punished for speaking their language, te reo Māori.

The results were dramatic: according to government data, in 1913, more than 90 per cent of Māori schoolchildren could speak the language. By 1975, that figure had plunged to less than 5 per cent.

Reclaiming culture

Today, tā moko is more popular than it has been in some 200 years, according to Ellis. Facial moko are visible in New Zealand's parliament, on professional sporting fields, in courtrooms and on TV news broadcasts.

In her maiden speech to parliament last month, Te Pāti Māori (Māori Party) MP Oriini Kaipara said Māori language and arts had only survived "because we fought for it, Māori and non-Māori alike".

In Australia, Victoria Police announced last month that it had updated its tattoo policy to allow a Māori constable to receive a moko kauae – making her the first officer in the state to do so. (The first member of Queensland Police to wear a moko kauae was permitted in 2021.)

It represents a step forward for cultural inclusion following several recent reports of Māori being denied entry to venues in Australia due to cultural tattoos, raising questions over whether anti-discrimination laws need to be reviewed.

In New Zealand, acceptance isn't universal either. In June, the country's foreign minister, Winston Peters, himself Māori, was criticised for referring to a Māori MP's mataora as "scribbles on his face", a comment many saw as emblematic of the prejudice that tā moko wearers still encounter.

The surge in visibility of tā moko has come hand in hand with other forms of cultural revival driven by political activism and community initiatives over the past five decades, including the establishment of Māori language schools such as Hona's.

Data from New Zealand’s 2023 General Social Survey suggests that 25.6 per cent of Māori and 6.2 per cent of the wider population can speak te reo at least fairly well.

There are more than 978,000 people of Māori descent living in New Zealand, according to 2023 NZ Census data, making up nearly 20 per cent of the total population.

A generational shift after 'a lot of pain'

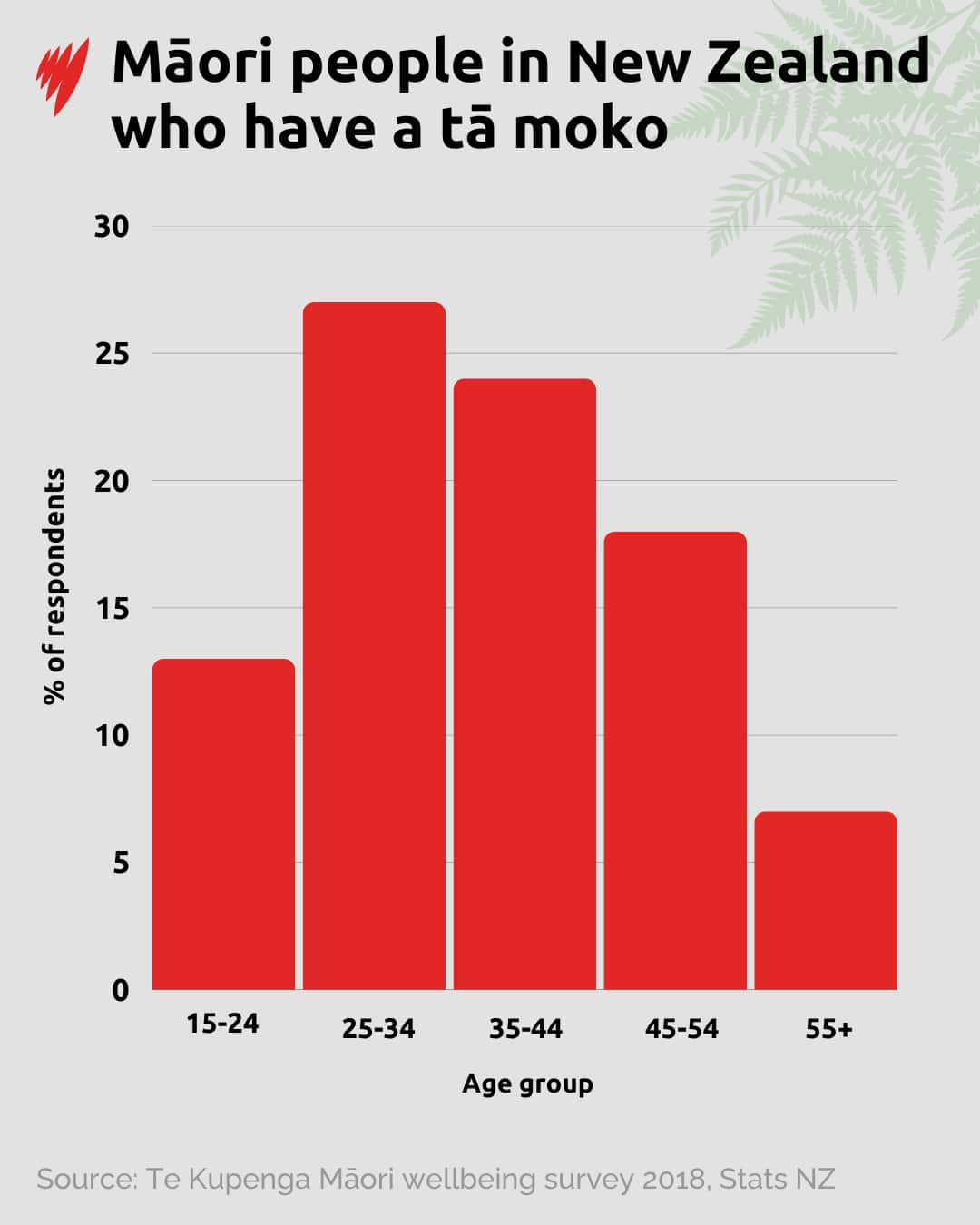

While there is limited data tracking the prevalence of Māori tattoos, a 2018 government survey suggested around 18 per cent of the Māori population bear a tā moko, up from 15 per cent in 2013.

The data also suggested a generational divide: younger Māori are far more likely to have one than those aged 55 or over.

Julie Paama-Pengelly has been a tā moko artist for around 35 years and has witnessed the revival of the art form firsthand.

"In the beginning, there was a lot of mamae, a lot of pain around it for our people," she tells SBS News.

"A lot of the elders didn't want it to happen. They just saw a period where it was difficult for them to wear these sorts of things.

"I guess it made them quite fearful of being oppressed because of it."

But she says now, there's "a huge movement" among those under 30, despite older generations remaining "more hesitant".

"From the era that they have been and not feeling proud of being Māori, it takes quite a lot to flick that switch and go: 'You know what? I can do this — and I need to do this for my children and my grandchildren,'" she says.

That being said, the majority of Paama-Pengelly's client base is aged between 40 and 80.

The 61-year-old says that’s mostly due to her own age, but explained that many older Māori decide to receive moko after reckoning with long-held beliefs about perception and worthiness.

Who can receive a tā moko, and when?

Many Māori choose to receive tattoos to mark milestones, such as becoming an adult, or simply to honour their ancestry at any time. For some, especially those receiving facial moko, a lot of deep introspection goes into the decision.

Paama-Pengelly was in her mid-50s when she decided to receive her own moko kauae from an artist who shared her genealogy. A lot of thought went into her decision, including whether her elders should have received one first.

Hona, who received his facial moko at 29, spent several years discussing what it means to wear a mataora and the responsibility that comes with it.

"When we grew up, we were told stories about earning. You had to earn the right to receive this and this type of moko," he says.

"It was acceptable to get everywhere else, but in your face, because it's so sacred, it was almost like a rule — a tikanga — that it was earned."

He recalls that his grandmother, who chose to receive a moko kauae later in life, challenged his belief that it had to be earned.

"Look, we're at a time now where we need to bring our art form back," Hona says, looking back on their conversation.

We are Māori. It's our right. And in order for us to revitalise that, we need to start wearing it.

Some artists consider tattooing non-Māori people, but it often depends on the recipient's intentions and understanding. Paama-Pengelly says she would not perform a facial moko for someone who is not Māori.

'Unashamedly Māori'

In 2023, New Zealand elected its most conservative government in decades, later formalised as a three-party coalition led by Prime Minister Christopher Luxon.

In the two years since, Luxon's government has sought to reshape various policies that affect Māori, reopening old wounds for many in the community.

Among the changes: winding back the use of Māori words in the public service and school curricula, abolishing the Māori Health Authority and an unsuccessful bid to review the Treaty of Waitangi — the 1840 agreement between Māori chiefs and the British Crown that upholds Māori rights and serves as a founding document of New Zealand.

Māori Party co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer said in 2023 that, in a matter of months, the new government had taken "us into a decline like we've never seen in race relations, certainly not since the earliest stages of colonisation".

Against that backdrop, the pride and symbolism represented by tā moko have become even more potent for some Māori today.

Paama-Pengelly says the government can't stop the momentum after four decades of cultural revival.

"You can't take it out of us anymore. You might think that you can make these decisions, but we're not going to go back," she says.

Ellis, one of only a handful of academics specialising in Māori art history, says: "There is nothing more that says 'I am unashamedly who I am' than by wearing a facial moko."

"It's a very clear statement: I'm unashamedly Māori, so deal with it."

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.