Feature

What would you do if you lost your job? Acclaimed director's new film has a dark answer

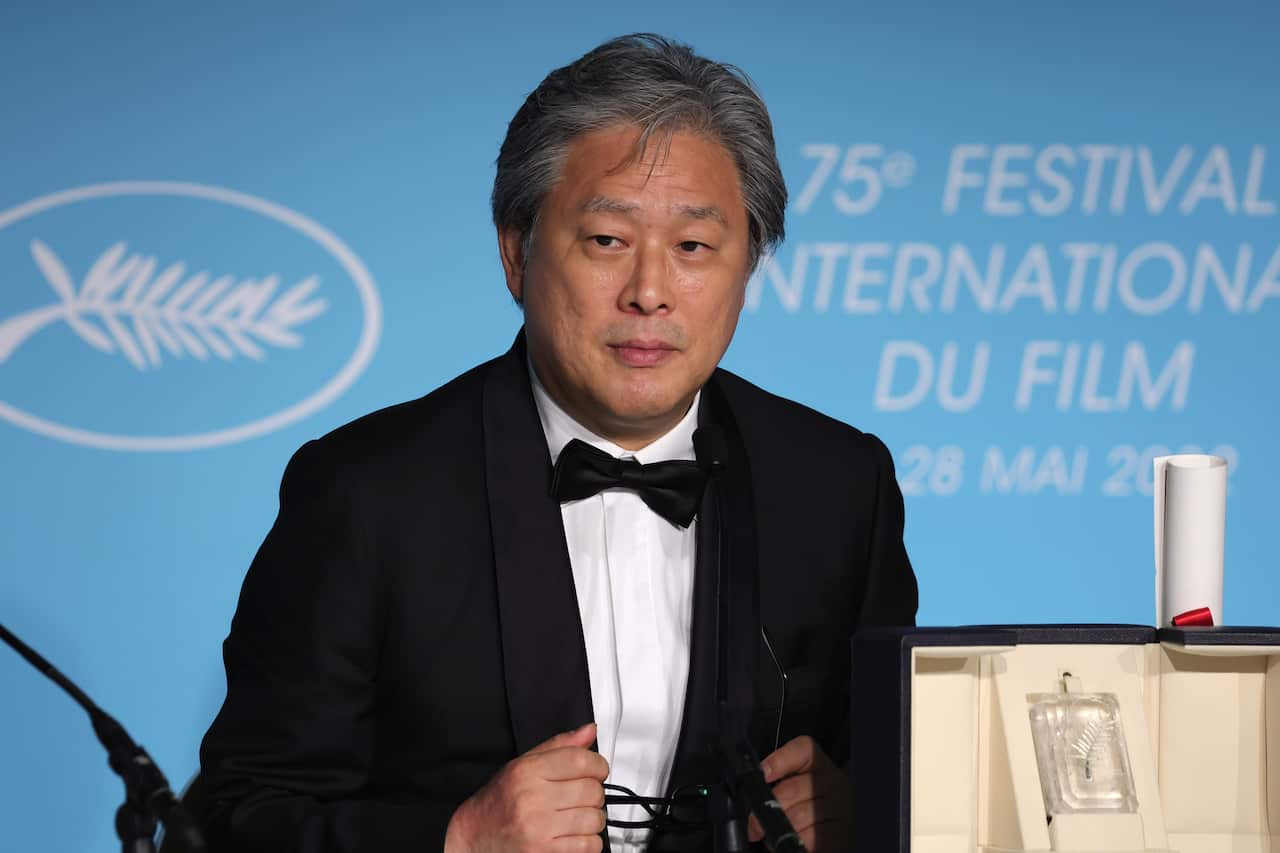

When your job defines you, losing it can have deadly consequences. At least that's the case in Park Chan-wook's thriller No Other Choice.

Published

Every day, we make choices. Cereal or eggs for breakfast. Whether to take the train or the bus. Whether to accept being made redundant … or brutally top anyone in the way of the job you want.

That last choice, at least, belongs to No Other Choice, the latest film from acclaimed South Korean director Park Chan-wook.

Park, known for films including Oldboy (2003), The Handmaiden (2016) and Decision To Leave (2022), has spent more than two decades probing the dark side of humanity and its thirst for revenge, power and pleasure (often with a healthy dose of blood and psychological mindf-ckery).

With No Other Choice, releasing in Australian cinemas on 15 January, Park turns his gaze to a quieter, more existential horror: what happens when a person's job — and the identity bound to it — disappears.

The film follows Yoo Man-su (played by Lee Byung-hun), a devoted company man laid off after 25 years at a paper factory. What begins as a familiar story of redundancy soon spirals into desperation. After a year of unemployment, Man-su decides to confront the job market head-on — by murdering his competition.

Brutal as it is, the story's logic is unmistakable. Park has spent decades exploring what makes people break, especially when systems and circumstances push them to the edge.

What do you devote your life to?

At its core, No Other Choice examines the idea that work gives life meaning — a theme Park says resonated with him more deeply than he initially expected.

"When I first heard about this story, I thought it would have nothing to do with me because it's about paper manufacturing, which felt so far from my life and from filmmaking," Park tells SBS News via a translator.

"But after finishing the story, I was very surprised at how easily I was able to empathise with it. There are quite a few similarities between paper manufacturing and filmmaking.

"Paper is something that most people look down on. They very easily crumple it up and throw it away, but then there are special kinds of paper that people do value, like bills or passports."

He explains that for some people, film and TV are viewed similarly, as "a meaningless source of entertainment" or "a way to kill time".

But for others, works of film and television can be very precious — even life-changing.

"Which is, of course, the kind of works that filmmakers strive to make as well," he says.

"I think that's why I was able to very easily empathise with the characters and the story, because it's a story about someone who has devoted their life to something that other people don't consider very important."

A distinctly Korean pressure

The film is adapted from Donald Westlake's 1997 novel The Ax, which also follows a family man eliminating his rivals in a shrinking job market.

But Park reworks the story through a distinctly Korean lens, sharpening its focus on class, familial obligation and the pressure to provide.

While anyone who has experienced redundancy may notice a recognisable anxiety soaking through the film, Park says the story is particularly emblematic of Korean society's relationship with work.

"Living in Korean society, I'm constantly thinking about and surrounded by the devastating state of people who have lost their jobs. Modern Koreans, especially, have become slaves of their jobs," he says.

"They spend most of their time at their jobs and they find the achievements from their job as their life's achievements as well."

Park notes that South Korea's social welfare system was introduced relatively late — and in stages over the 40 years leading up to the early noughties — intensifying the consequences of domestic job losses.

"Up until a few years back, people would be placed in a very hopeless state if they lost their jobs," he says.

"We would hear about people who would kill their family after they lost their job and then eventually also kill themselves because they had no hope for the future."

Those real-world tragedies also influenced his 2002 film, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance.

"I remember feeling very shocked by news articles about that," he says.

"Reading The Ax, I was remembering those incidents and I think I was influenced by the societal circumstance around me as well."

Stream free On Demand

Thirst

Watch Park Chan-wook's 2009 horror-mystery Thirst on SBS On Demand.

Watch Park Chan-wook's 2009 horror-mystery Thirst on SBS On Demand.

Pressure to perform

Despite his global acclaim and having a spate of international awards and accolades, including a BAFTA and multiple awards at Cannes Film Festival, the director remains acutely aware of how success operates within filmmaking — not simply as validation, but as leverage.

"The sad characteristic or fate of filmmaking is that you can't do it alone," he says.

"So unlike composing music or drawing a picture, it requires a lot of people and a lot of money to make.

"And unlike other artists like painters or poets, filmmaking requires you to care about what others might consider worldly desires — such as box office scores or awards or good reviews."

Despite his influence on global cinema, Park has never been nominated for an Academy Award.

He previously described it as "hypocrisy" to pretend awards don't matter. Not because they define artistic worth, but because they can determine whether the next film gets made.

"I make films that require a certain level of capital to be invested. I also want creative freedom when I'm making my films as well," he says.

So I can't help but accept that I also require the so-called worldly success in order to continue in my career.

It's an understandable concession: an award can come with more power, more creative freedom, and bigger budgets.

Just look to Bong Joon-ho, the other globally-renowned titan of South Korean cinema, whose career skyrocketed after his film Parasite won multiple Academy Awards, including best picture — the first non-English language film to do so.

That win brought more eyes to Bong's work and with it, more trust, manifesting in funding — a reported $150 million for his following project, Mickey 17.

In No Other Choice, the paper company operates as an invisible authority, quietly determining Man-su's value. For filmmakers, Park suggests, the industry can function in much the same way.

Stream free On Demand

The Handmaiden

Watch Park Chan-wook's 2016 thriller-romance The Handmaiden on SBS On Demand.

Watch Park Chan-wook's 2016 thriller-romance The Handmaiden on SBS On Demand.

A 'bitter taste' in a world without film

In that sense, the film is also a meditation on identity and purpose — and the forces that shape them.

For Park, it's in part an opportunity to reflect on his sense of self and who he is outside of filmmaking.

I actually thought about that a lot while working on this film and I realised that I have to work on expanding other areas of my life other than just being a filmmaker.

"Working on my identity as a member of my family and also as an independent individual as well."

But when faced with the prospect of his vocation being taken away, as it is for his protagonist, Park is deeply introspective.

"I guess if I were to imagine a world in which I wouldn't be able to make films, it leaves a very bitter taste in my mouth."

No Other Choice is in Australian cinemas now.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.