There was a time, not long ago, when the occupant of the White House held a beer summit to bring together a white police officer and the black professor he had mistakenly arrested. Another time, after the shooting death of a black teenager by a neighbourhood watchman resulted in a storm of protest, that president remarked that the victim looked like he could have been his son.

When it comes to race, the most jarring difference between the Trump presidency and that of Barack Obama is not necessarily the nature of the ugly incidents playing out across the country under their watch.

After all, the arrests of two black men waiting at a Starbucks was preceded by Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Harvard professor, being hauled away in handcuffs when a white neighbour thought he was breaking into his own home. The kneeling protests at NFL games followed the death of Trayvon Martin, the black teenager killed by a neighbourhood watch volunteer, not to mention a string of high-profile police shootings of unarmed black men.

The most striking difference between then and now is the responses of the commanders in chief, and how those reactions affect the country’s long-simmering racial tensions.

President Donald Trump sometimes uses familiar phrases that seek to evoke America’s better angels — before signing a proclamation for Martin Luther King Jr.'s Birthday in January, he reminded that all are created equal “no matter the colour of our skin.” But other words and deeds are racially inflammatory — around the same time he referred to Haiti and some parts of Africa as “shithole countries” in closed-door remarks that were leaked.

His predecessor, Obama, sought out a language on race that was heavy on balm. When Obama eulogised black parishioners murdered by a white supremacist at Emanuel African Methodist Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he famously sang Amazing Grace. Still, some people, mostly white, accused him of dividing the country when he spoke empathetically about the racism faced by black Americans.

The divergence in the way the two men have chosen to handle racial flare-ups was perhaps inevitable. Obama, as the first black president, had to overcome racism on his way to and during his time at the White House, including questions over whether he was actually born in the United States. And the very name of his more impulsive successor has become a kind of shorthand racial taunt.

“I think that sense that there’s no leadership, there’s no one sort of guiding Americans to question and to think about all of these tragedies that are occurring right now, makes it all the more anxiety provoking,” said Allyson Hobbs, a professor of history who is director of African and African-American studies at Stanford University.

But Obama was not without his own challenges when it came to leading the country’s racial discourse.

When he attempted in 2009 to be critical of the white police officer who had arrested Gates, saying that the officer had “acted stupidly,” he stirred the ire of police and conservative groups. And even in trying to backtrack and ease the flames, Obama invited more criticism, this time from African-Americans, who believed he was being too deferential.

Trying to heal the country’s racial wounds is an uphill battle for any president. A CNN poll taken near the end of Obama’s presidency found that 54 percent of Americans thought that relations between black and white Americans had gotten worse during his eight years in office. A Pew survey from December found that 60 percent of Americans believed that Trump’s election had hurt race relations.

This week, he took to Twitter to respond to the tweet by television star Roseanne Barr in which she compared a former Obama aide, Valerie Jarrett, to an ape. But Trump did not condemn the offensive tweet, or speak about race. Instead, he used the opportunity to complain that critics who had spoken ill of him had not apologised. The president continued on that theme Friday morning, wondering on Twitter why Samantha Bee had not been fired from her show for using vulgar language to describe one of his daughters.

Trump manages to deftly turn racial issues into left-right political fights that are race neutral, said Ernest Lyles, a black private equity partner who lives in New York. In the case of Barr’s comments, for instance, Lyles said the president turned what was simply an issue of someone making a racist comment into a battle between a liberal television network doing wrong to a Republican like him.

And Lyles, 39, said he found that unfortunate because he believed Trump could actually do more to heal the country’s racial divide than Obama, because the people who listen to Trump are less savvy on racial issues.

“Unfortunately, for better or worse, America is trained to be more open, and more conditioned to be led by, a white male than someone who isn’t,” Lyles said.

Despite the concerns that Trump has helped fuel the country’s sometimes toxic racial climate, recent events demonstrate that there are still consequences for racial discrimination, and racist acts.

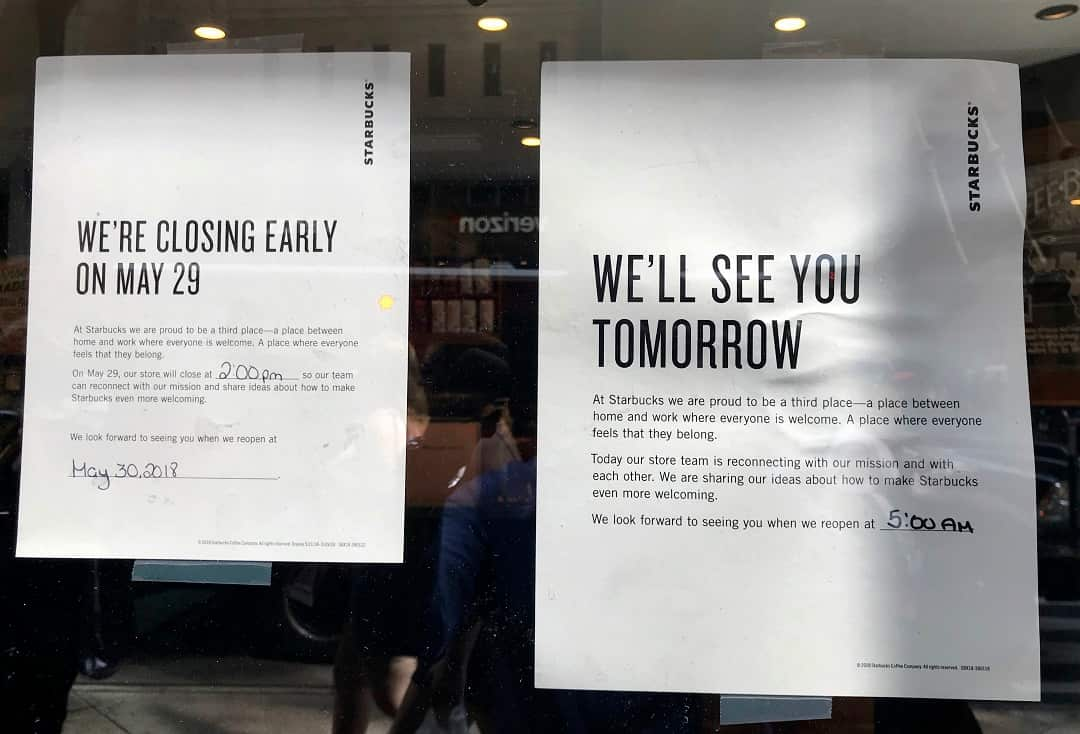

On Tuesday, the cafe chain Starbucks closed 8,000 stores to give its employees racial sensitivity classes — a response to an incident in April in which a pair of black men who had gone to a Starbucks in Philadelphia for a business meeting were arrested on suspicion of trespassing. Starbucks had considered itself a progressive company, making the incident all the more troubling.

After the arrests, the company’s reputation as a place to work sank to its lowest level in at least a decade, according to YouGov BrandIndex, which tracks public perception of companies. Data from SEMrush, a Google Search analytics tool kit, shows that the number of search queries for the phrase “Boycott Starbucks” surged from a mere 500 in March to more than 70,000 in April.

For some observers, the chain’s response, however self-serving, demonstrated the growing power of the minority consumer, a power that retail and entertainment companies are particularly attuned to in a country whose population is expected to be less than 50 percent non-Hispanic white by 2045.

“As black income has risen — as desegregation has marched forward, and as corporations realise the extent to which black dollars are an integral part of their bottom line — we see a kind of enlightened self-interest in the American corporate and business sectors,” said Lolis Eric Elie, an African-American writer who has worked on several television shows, including “Treme.”

The store closings came on the same day that ABC Entertainment, the network that broadcast the hit reboot of Barr’s sitcom, Roseanne, announced it was cancelling the show, which had been seen as an explicit outreach by a mainstream media company to Trump voters.

The announcement, which called Barr’s tweet “abhorrent, repugnant and inconsistent with our values,” came from Channing Dungey, the ABC Entertainment president and the first black executive to run a major network.