Feature

Refugees, foreign students and 'boat people': What it's really like to migrate to Australia

As SBS celebrates 50 years of storytelling, we share the stories of those who made the at times perilous journey across the seas in search of freedom, safety and a sense of home.

Published

Updated

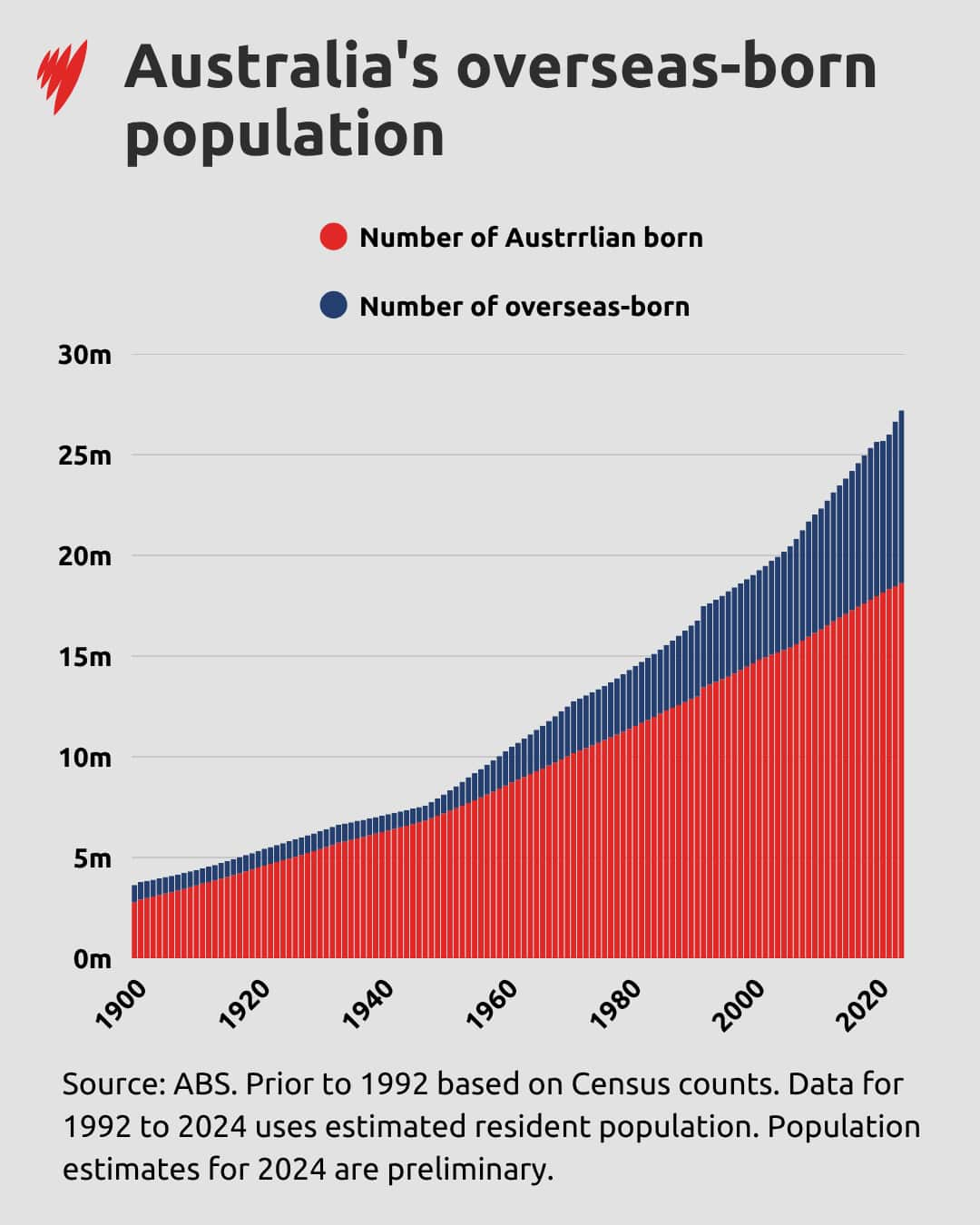

Australia has long been a nation of many cultures.

For at least 60,000 years, hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups flourished, each with its own distinct language, customs and lore.

The invasion of British settlers in the late 18th century precipitated decades of colonial violence and dispossession, yet many groups resisted and survived. Today, there are more than 150 First Nations languages still spoken across Australia, making it home to one of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth.

Since the arrival of the First Fleet, millions of others have crossed the seas, seeking to call this vast continent home.

But who has come — and been allowed to stay — has fluctuated greatly.

The gold rushes of the 1850s attracted migrants primarily from the United Kingdom, Europe and China, while thousands of South Sea Islanders were brought to Queensland in the second half of the 19th century to work on sugar plantations.

After Federation in 1901, the first national immigration law was introduced, which became known as the White Australia policy. It primarily targeted people of Asian descent and was widely denounced as xenophobic, restricting non-British migration to Australia well into the middle of the 20th century.

The post-war years witnessed a boom in immigration from continental Europe, but with successive waves coming from the north-west, followed by southern and eastern Europe.

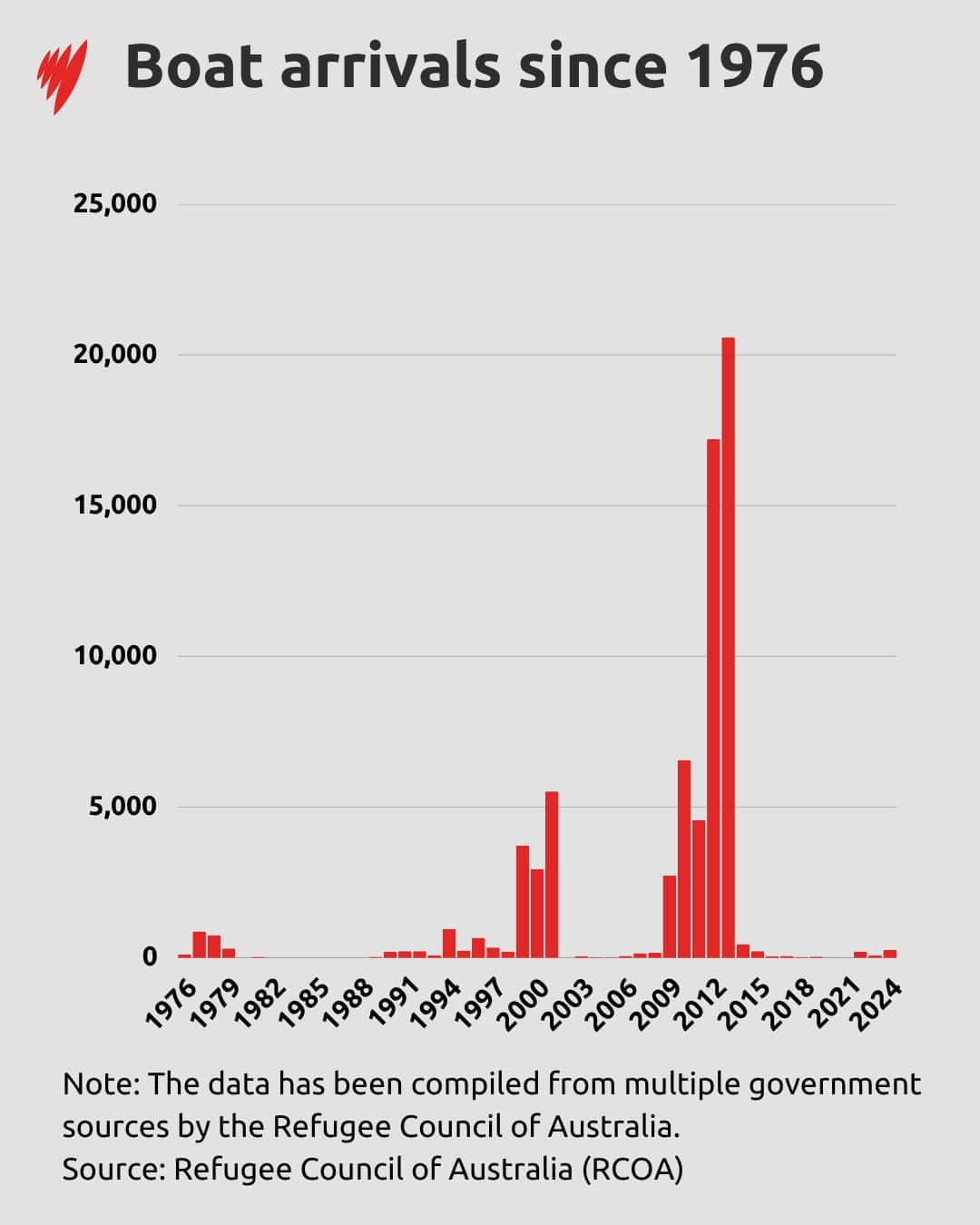

Then, in April 1976, following the end of the Vietnam War, a boat carrying a small group of Vietnamese men reached Darwin Harbour. They became known as Australia's first 'boat people' — a term that would come to shape policies and attitudes for the next 50 years.

To mark this chapter and SBS' 50th anniversary, SBS News brings you the stories of five people who, in search of safety, freedom, education and a better life, have journeyed across the seas to make Australia home.

- Click to view an interactive version of this story

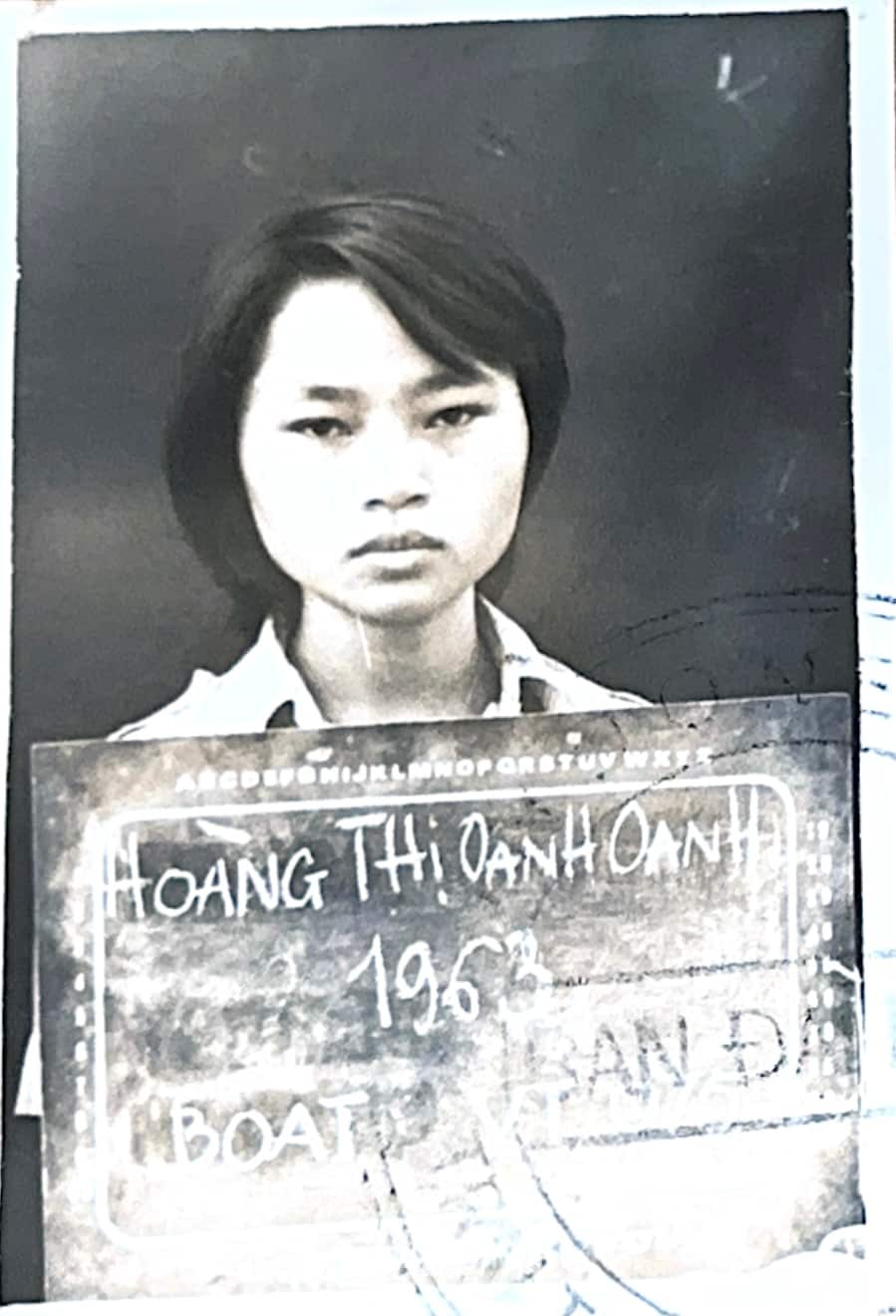

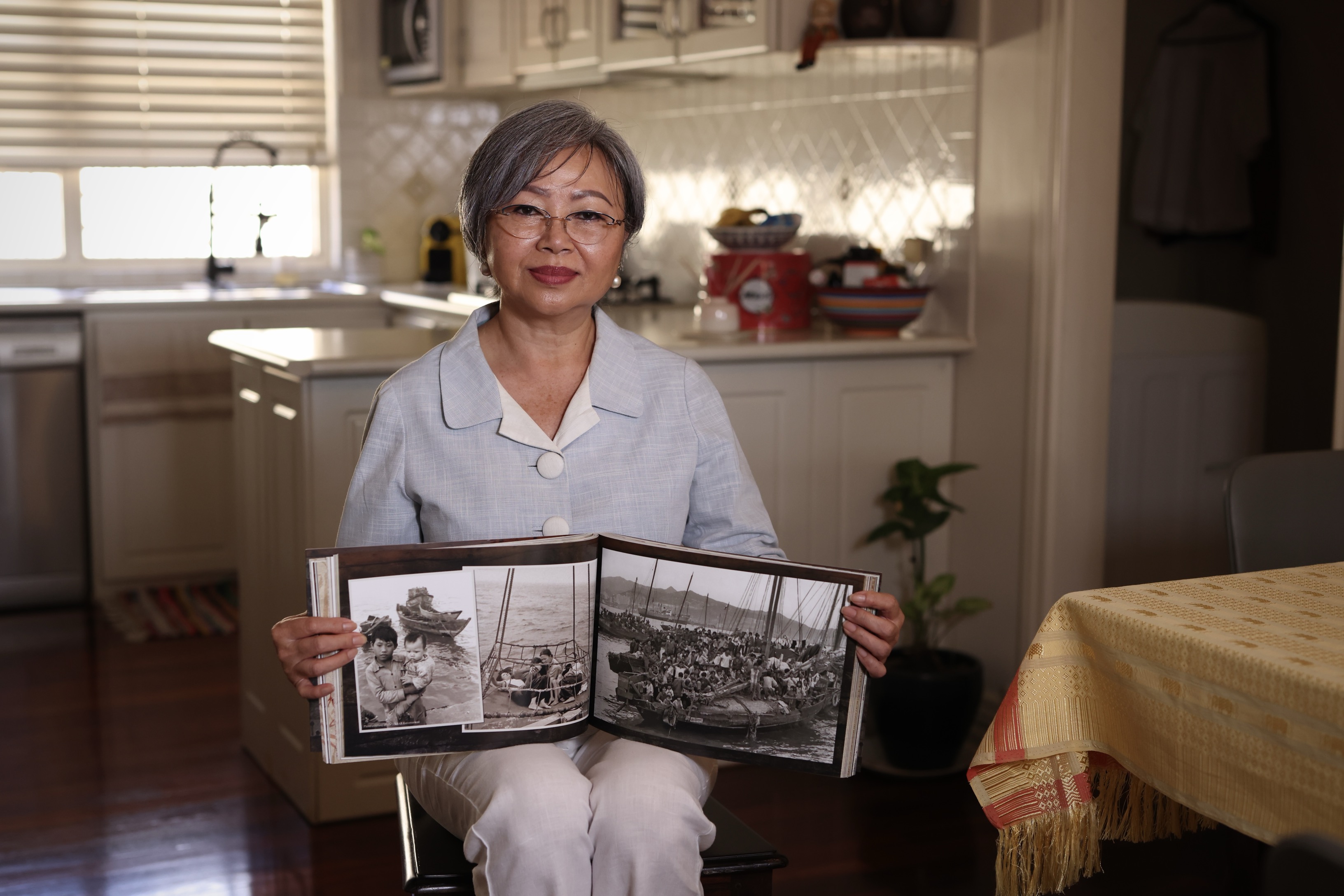

Dr Carina Hoang was 16 years old when she fled war-torn Vietnam with two of her younger siblings.

It was May 1979, and the trio boarded a small wooden boat — 24 metres long and four-and-a-half metres wide. On board with them were around 370 others.

"We were packed in four layers of people, like sardines," Hoang says.

Hoang was born several years into the Vietnam War in 1963. Having never known life outside of wartime, she describes her childhood in Saigon with her six siblings as relatively "normal".

"The only difference was we didn't get to see our father often because he was always at his military base or out in the field fighting," she says.

Hoang's father served in the South Vietnamese military and would later be imprisoned without trial for 14 years by North Vietnamese authorities.

Towards the end of the war, Hoang recalls hiding in a bunker inside her family home for days and nights on end as the conflict intensified.

On 30 April 1975, North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon — modern-day Ho Chi Minh City and the former capital of South Vietnam.

That was the day the war ended, and it changed our life in ways that we could never, ever imagine.Carina Hoang

Just before Saigon fell, the United States and other foreign forces evacuated thousands of civilians and personnel.

Hoang remembers a city in "chaos". Her mother gathered all seven children and one of their cousins and took them to the US embassy, where they waited in line for hours, hoping to be airlifted out.

"Many helicopters came up and down, and each time, I think they would only take 20 people. I don't know how many hours we were there, until all of a sudden, the soldiers just closed the door, turned around and pointed for all of us to go back downstairs."

Within hours of leaving the embassy, the South Vietnamese government surrendered. Hoang says her family's home was seized, her father was taken from them, and her mother's business was frozen.

They became homeless overnight.

After several attempts to leave the country over the next few years, Hoang, along with one of her sisters and one brother, finally escaped by boat. Two of her other siblings had managed to escape earlier, while another two remained in Vietnam with their mother.

Conditions aboard the vessel were filthy, and the waters were pirate-infested. They eventually docked at an uninhabited Indonesian island, which later became a makeshift refugee camp.

There was no food, and Hoang and her siblings, then aged 12 and 10, were forced to walk through the jungle in search of drinking water. Locals started exchanging food for money or valuables, but things remained scarce. Early on, the siblings would survive for days at a time on a single pack of ramen noodles.

"I sold my mum's diamond rings and earrings to get money for medicines and for food," Hoang says.

Ahead of their journey, Hoang's mother had packed the siblings some rock sugar, salted plums and Vietnamese medicinal oil, along with sets of clothes and one of her traditional dresses.

"I love those outfits, but in retrospect, I think my mum … didn't know what lies ahead," she says. Hoang instead "protected them" and still has the dress to this day.

They would stay on the island for 10 months before being resettled with help from the Red Cross. Many others were not so lucky — hundreds died due to sickness and malnutrition.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), around three million people fled Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and other communist victories.

Australia's then-prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, was widely credited for accepting Southeast Asian refugees. Between April 1975 and March 1991, more than 130,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were resettled here, according to Rachel Stevens, a lecturer from the Australian Catholic University who specialises in immigration and refugee policies.

The 1970s also marked two major turning points for immigration policy in Australia: the formal dismantling of the White Australia policy by the Whitlam government in 1973 and the introduction of the Racial Discrimination Act in 1975, which made it unlawful to discriminate against a person because of their race, descent, national or ethnic origin or immigrant status.

However, Stevens says Australia's intake only ramped up in 1978-79. She attributes this to the 1976 arrival of 'boat people' for the first time, which "forced the Fraser government to formalise the refugee intake process".

The government implemented the nation's first refugee policy the following year, and a humanitarian program was introduced.

At the same time, the term 'boat people' became associated with "unauthorised" migration, Stevens says. Between 1975 and 1982, there were just over 2,000 Vietnamese people who arrived by boat without authorisation, according to records from the Parliamentary Library of Australia.

"We're talking about a tiny percentage of Vietnamese refugees who came 'illegally', without government support, and yet it has framed our thinking about immigration in general."

Madeline Gleeson, a senior research fellow at UNSW's Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, points to a "long-standing resistance to – or even a fear of – the idea of people coming to Australia spontaneously or by unauthorised means".

"Particularly from the 1970s onwards, we started to see a growing public and political concern with people arriving by boat from countries to our north to seek asylum, and the beginning of a sense that there was some sort of uncontrolled or overwhelming number of people that might be trying to reach Australia in this manner."

Despite Australia's "relatively generous approach" at the time, she says the origins of a division between "genuine" and "non-genuine" refugees emerged — an "undercurrent of the political discourse that we see today".

It would be many years before Hoang made it to Australian shores.

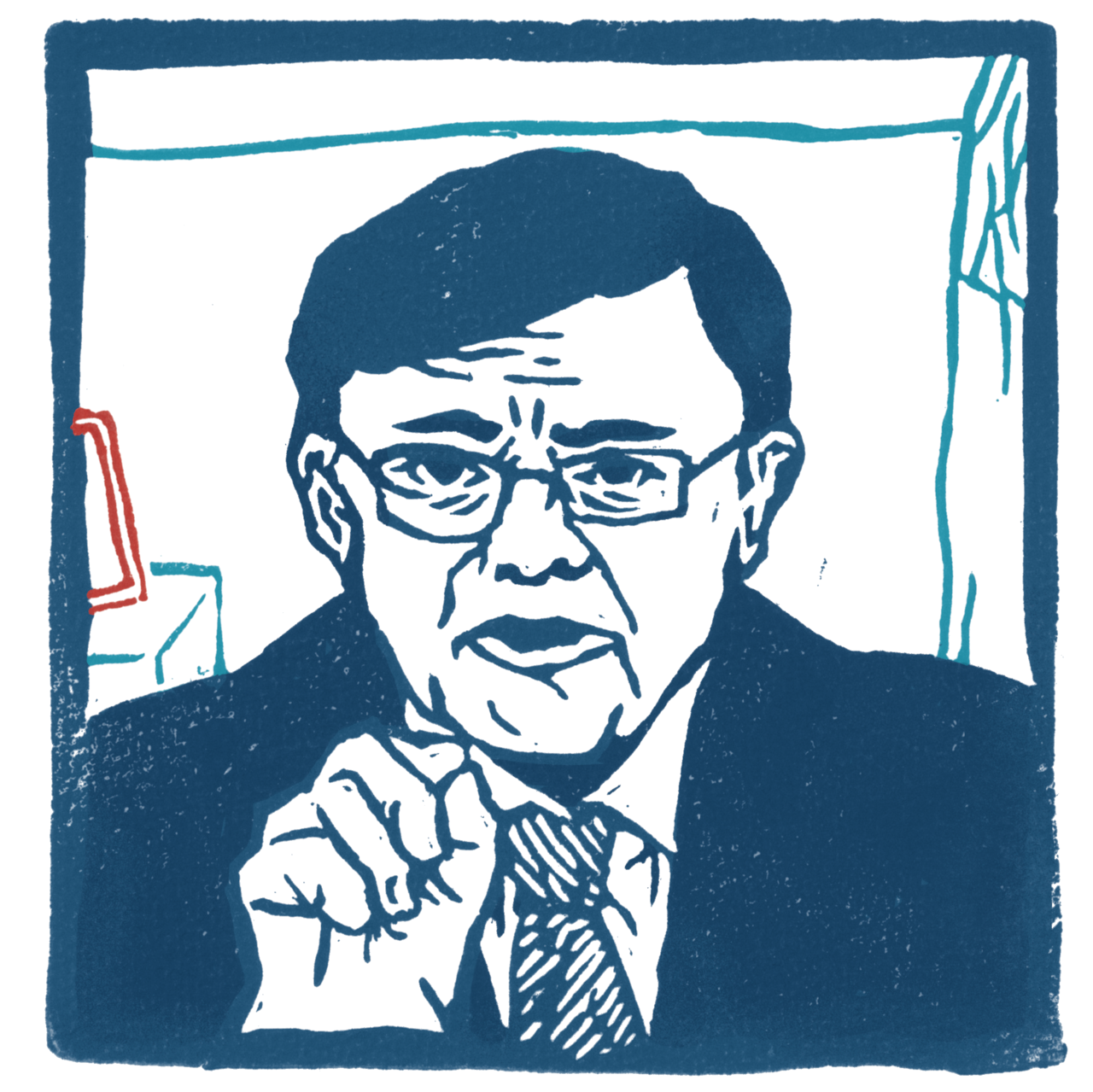

Chin Jin remembers clearly where he was on the day of the Tiananmen Square massacre.

In the early hours of 4 June 1989, Chinese troops and tanks reached student demonstrations that had been taking place in Beijing's Tiananmen Square and started to open fire at protesters.

It followed weeks of pro-democracy protests after the death of former Communist Party of China chief Hu Yaobang, who had sought to liberalise the country.

Chin, then 32 years old, had arrived in Sydney months earlier and was staying at a friend's house when the news broke.

"I feel my heart was beating together with the people in Tiananmen Square," he says.

He recalls asking his friend to drive him to Chinatown, where many Chinese students were gathering.

"Everybody was weeping and shouting. All these students showed their anger towards the barbaric Chinese government. I was one of them."

Days later, then-prime minister Bob Hawke delivered a tearful tribute to the victims of the crackdown. Afterwards, he announced Chinese students would be allowed to remain in Australia.

Some 42,000 permanent visas were granted to Chinese citizens — including Chin.

"We were so lucky. Nobody had any idea that could happen," he says.

"I still feel very grateful to Bob Hawke … to make this generous decision to allow such a large group of people to stay in Australia."

While the move was seen by many as compassionate, Stevens says it ruffled feathers within the bureaucracy.

"For a prime minister, who is not even minister for immigration, to make a unilateral decision like that, it was unprecedented," she says.

"I think it's being remembered as a really positive step of an Australian prime minister showing compassion. But if you look under the hood, it's actually something much more troubling."

The decision allowed Chin to continue his life in Australia.

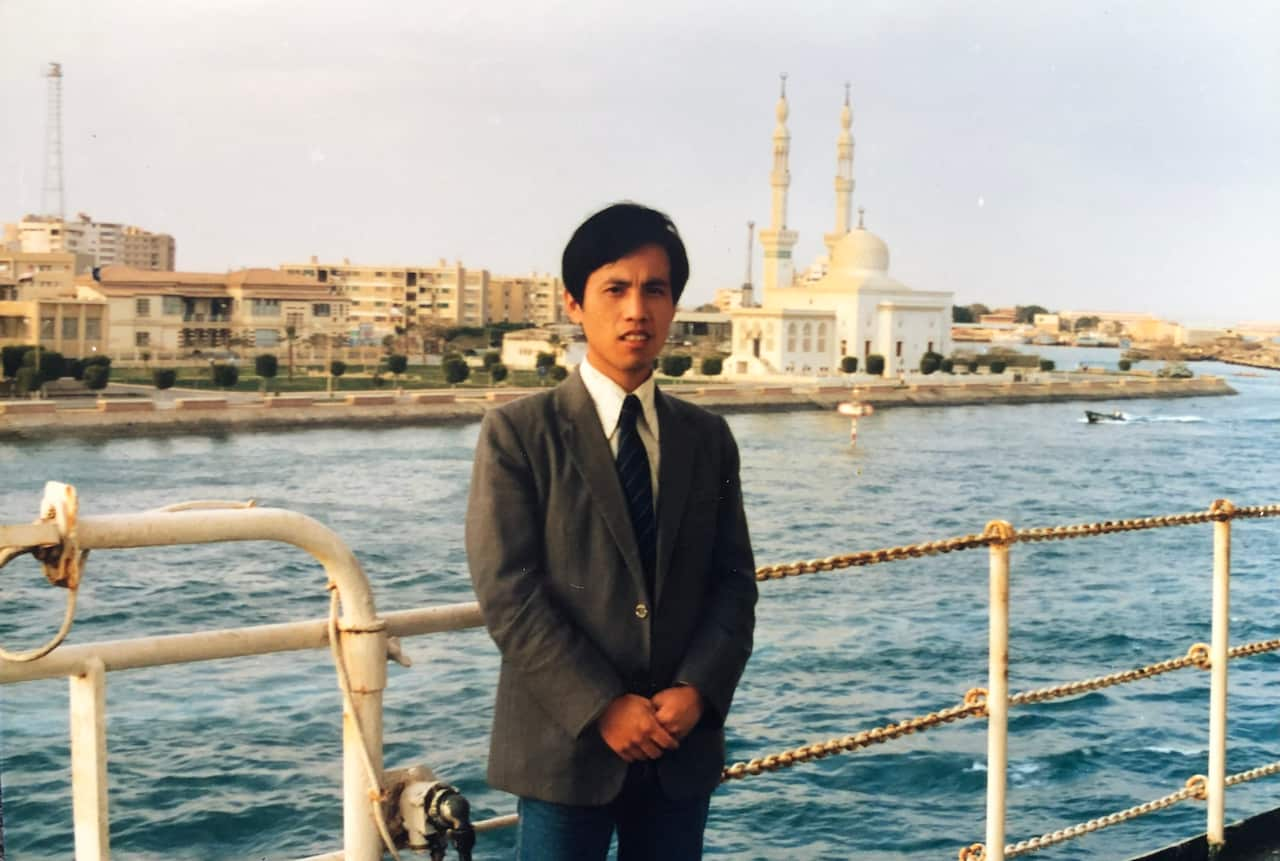

Born into a working-class family in the Chinese province of Jiangsu, Chin says he was fortunate to have access to education and pursued marine engineering at a tertiary institute similar to TAFE. He later worked for a Chinese shipping company, leading to his first treacherous journey to Australia in 1982.

"We almost lost our lives," he says, of the trip aboard a cargo ship to the industrial port of Dampier in north-west Western Australia.

In 1988, he seized the opportunity to move to Australia to study English, travelling by plane from Shanghai to Sydney.

"When I first arrived, I noticed life was very tough — a totally different life between Australia and China," he says.

"The living expenses were very, very expensive. Without any job or income, we could not survive."

Chin started out as a kitchen hand. After Hawke's decision, he worked in a factory, beginning to enjoy a "peaceful, quiet life". But his sights were always set further.

My ambition was not only to stay in Australia; my ambition was to bring freedom and democracy back to China.Chin Jin

Chin is now the president of the pro-democracy organisation Federation for a Democratic China, which was set up in the wake of the massacre, and describes himself as a researcher in the modern Chinese democracy movement.

He says his journey to Australia was a "successful" one.

"Without that, if I were to stay in China, I believe I [would] be in jail because of my political thinking.

"I still cherish hope in the foreseeable future [that] we could see a big change in China."

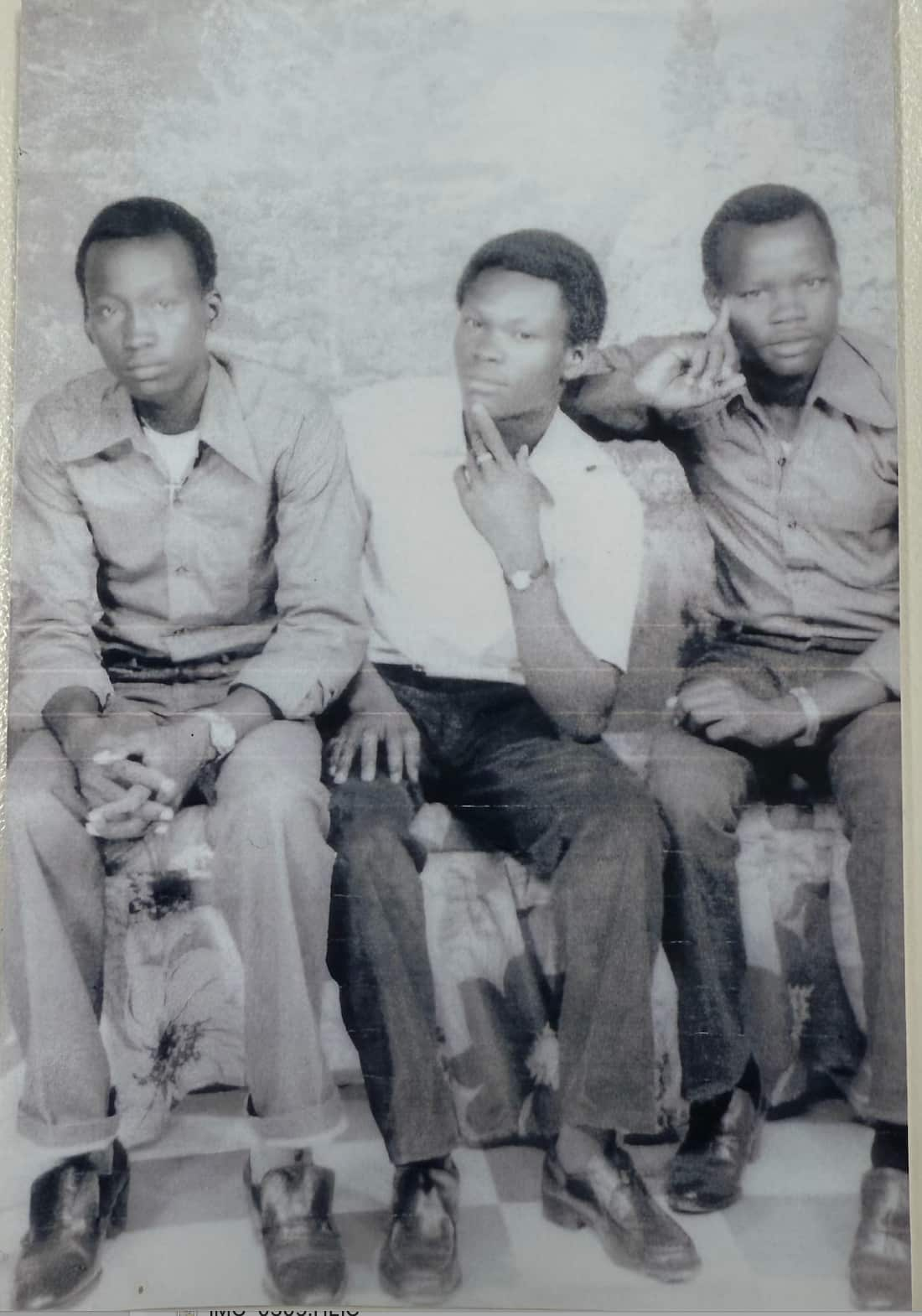

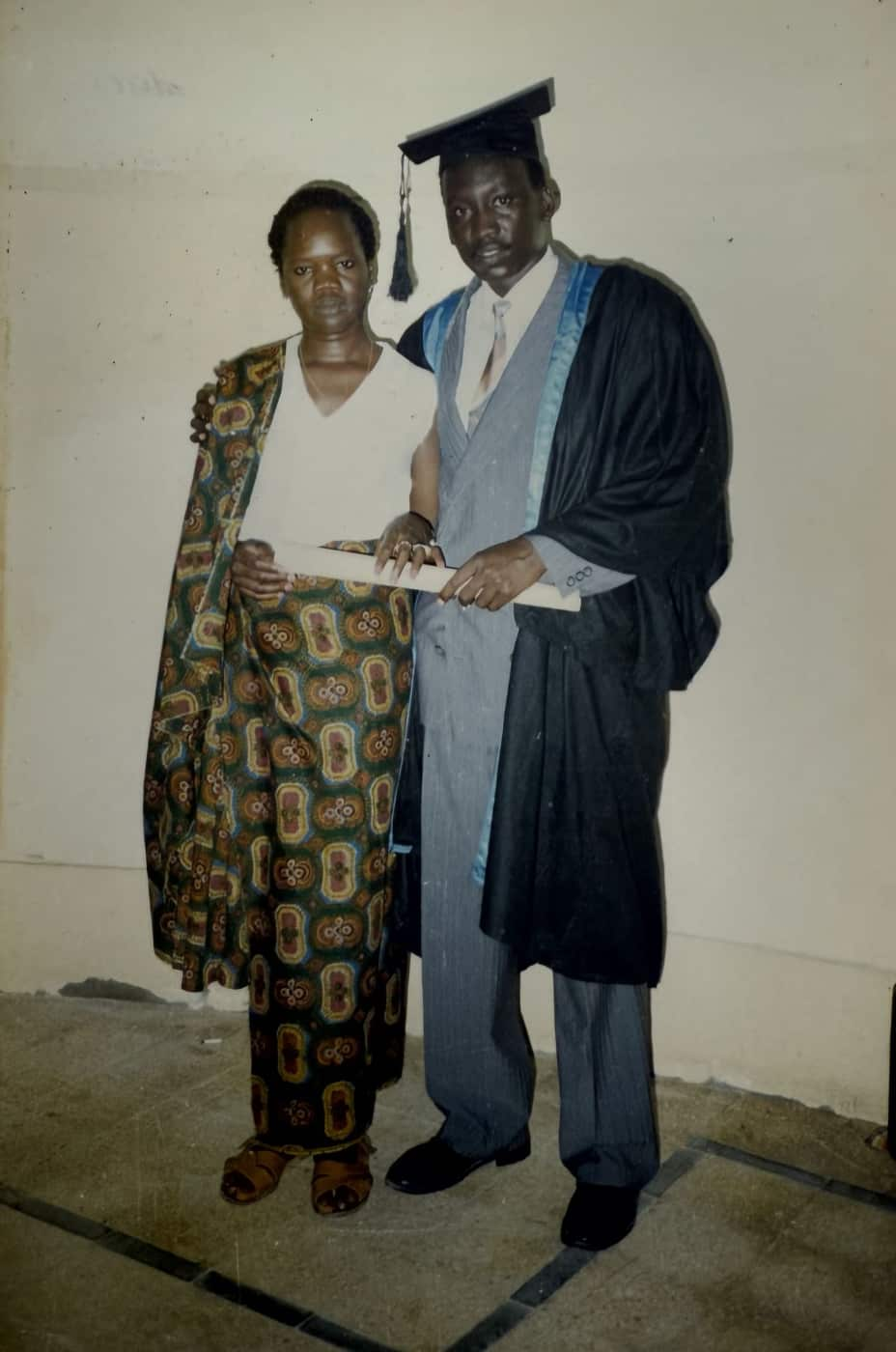

With civil war waging in his home country, Deng Athum faced a stark choice: join the fight in South Sudan and risk being killed, or leave and seek refuge.

It was the late 1990s, several years into the Second Sudanese Civil War. Athum was studying in Egypt and had planned to return home to teach, but couldn't.

"At that time, I didn't even know that there was [a country] called Australia," he says.

"But I had two friends who came before me … They found that this place was a good place to live and to make a good future."

With support from his friends, Athum and his wife were granted humanitarian visas and flew from Cairo to Sydney in 1998. He was 26, with a dream to continue his studies.

"But I did not know what I was coming to face."

Athum found a "land of abundance".

But when he arrived, his thoughts kept turning back to those left behind in the warzone. He and a friend worked with immigration officials to help others immigrate to Australia.

South Sudan gained independence in 2011. Two years later, Athum returned to his studies, pursuing a master's degree in education leadership.

"That is the thing that I did for myself," he says.

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Australia also experienced an influx of refugees from Syria, Iraq and the Balkans.

Stevens says there was a resurgence of people arriving by boat without authorisation and seeking asylum over the decade also. This followed a period between 1982 and 1989 when boat arrivals had dropped to zero.

In response, Hawke's successor, Paul Keating, introduced mandatory detention of asylum seekers in 1992.

Australia's South Sudanese community was established mostly by refugees who had been displaced by the war, which spanned 1983-2005. The largest numbers arrived between 2003 and 2006.

Athum has now lived here for 26 years and is an Australian citizen. He has seven children – among them: a midwife, an assistant nurse, and law and engineering students.

"I'm very proud of them," he says.

In recent years, he has seen his community become the centre of negative media coverage and political rhetoric, associating young South Sudanese men with crime and the so-called Apex gang in Melbourne. Police later declared the crime group a "non-entity", with then deputy commissioner Shane Patton telling an inquiry a large cohort "was in fact Australian-born offenders".

In a 2018 radio interview, Peter Dutton, who was home affairs minister at the time, said Melburnians were "scared to go out to restaurants" at night due to "African gang violence".

Athum acknowledges there are "good and bad people" in any community, but says there was "a lot of name-calling going on", which was addressed by prominent community members at the time.

We have to treat ourselves as humans. We've been here for a long, long time … we are Australian, we are working and we are paying tax.Deng Athum

Athum and his family are preparing to open a restaurant showcasing local dishes in the western Sydney suburb of Blacktown.

"Australia is a multicultural country, where everyone comes to make Australia home, to show what they have in their home. [With] this restaurant, I'm bringing South Sudan right here in Australia … to showcase what kinds of food that we cook," he says.

With escalating violence spilling over from the conflict in neighbouring Sudan, there are warnings that South Sudan may be on the brink of a return to civil war. Athum has been in touch with loved ones – and is once again fearful of the country's future.

"But the leaders are doing their best for this not to happen … I'm optimistic that South Sudan is not going to collapse."

The first time Asif Ali Bangash saw big seas was when he fled his home country by boat, in search of safety.

Bangash is a minority Shia Muslim from the city of Parachinar in north-west Pakistan, which has a history of sectarian violence.

"I fled from Pakistan because of the situation in my hometown," he says.

"I came here [to Australia] by boat in 2012, which was very dangerous and scary for me."

At the time, Bangash was 22 years old. Leaving his parents and brothers, he travelled to Malaysia and Indonesia before coming to Australia.

"It was a small, wooden boat … we were 200 people on the boat, and we [would] just think about that it can sink [at] any time," he says.

"But still I had hope that I can go and reach [the] safe place."

Bangash recounts rough seas at night, where they "didn't see anything".

There was no hope at night time. At one point, I was just thinking, 'we are all dying very soon'.Asif Ali Bangash

Bangash reached Christmas Island, a remote Australian territory off the far north coast of Western Australia and the site of an immigration detention centre. It was emptied of detainees in October 2023.

After one month, he was transferred to the now-closed Curtin Immigration Detention Centre in the Kimberley region of WA, where he spent two months.

He experienced dehydration and pain — for which he was hospitalised for a week — along with anxiety and depression.

"Psychologically, it was pretty much like prison. You can't go outside … you don't have any friends to bond with; to sleep, you don't have your own space in the room or anything like that," he says.

"All the people who came with you in the same boat [are] getting out of detention, one by one, and you are the last."

Bangash obtained a bridging visa while in detention at Curtin and was later transferred to community detention in Sydney, but his subsequent attempts to secure a protection visa were rejected. Unable to return home, he twice applied for ministerial intervention. Both his parents died while he was awaiting a determination.

After 13 years in limbo, without work rights, healthcare or social support, Bangash was granted a permanent visa in March this year.

Building a life and community in Sydney, Bangash now volunteers at Parliament on King in Newtown – a cafe and social enterprise that supports asylum seekers and refugees. He also donates blood to help "give a life back".

Australia's policy towards asylum seekers and refugees gained attention in the early 2000s.

In August 2001, a Norwegian freighter, MV Tampa, rescued 433 mainly Hazara asylum seekers who were in distress in a small fishing boat about 140 kilometres north of Christmas Island, in what was considered international waters.

At the time, Hazaras were fleeing Afghanistan, fearing persecution from the resurgent Taliban.

The Howard government refused to grant the ship permission to enter Australian waters.

It proceeded to pass a series of laws known as the Pacific Solution, which meant asylum seekers arriving by boat could be detained and their claims for refugee status processed in offshore centres on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

Another centre was set up on Christmas Island, with the government cutting off the territory from its migration zone. This barred access to refugee determination processes followed on the mainland.

Agreements were secured for the Tampa asylum seekers to be taken to New Zealand and Nauru, as Howard positioned his government as tough on border control ahead of the 2001 election.

Along with mandatory detention, iterations of offshore processing have defined Australia's stance over successive governments and have repeatedly raised concerns among human rights groups and UN agencies.

Offshore processing continued until 2008, by which time boat arrivals had declined and facilities had been emptied. The incoming Rudd government acted on an election promise to dismantle the Pacific Solution.

Replacing Rudd in 2010, Julia Gillard commissioned an expert panel, which recommended a range of measures, including offshore processing. The policy was reinstated in 2012 and has been in place ever since.

"Offshore processing was never meant to be the main pillar of Australian immigration policy, but in practice, it became the sole pillar for an extended period," Gleeson says.

In July 2013, a returned Rudd government announced that resettlement would no longer be available for any refugees offshore.

"We had a significant number of people offshore who had been or were about to be determined to be refugees. They were being released from the detention centres in Nauru and on Manus Island, but there was nowhere for them to go from there," Gleeson says.

"So began a period of Australia quite frantically trying to find third countries with whom to conclude settlement agreements."

Despite a formal policy being in place, offshore transfers only occurred until 2014, when detention centres became full. The government then pivoted its focus towards maritime interception and turnbacks.

"From 2014 to 2023, nobody arriving in Australia by boat was sent offshore … By 2023, the people who had arrived almost a decade earlier were transferred — either resettled or repatriated. Since late 2023, Australia has begun transferring a new group of people offshore, and we know very little about their processing, their status or their conditions," Gleeson says.

Decades on, Gleeson says the generation of "artificial fear" around asylum seekers arriving by boat remains, "rather than that being portrayed as a reality of the world and something which can be effectively managed with a properly organised system".

Reflecting on his own journey, Bangash says he'd always imagined a better life in Australia — a place where there would be "more humanity". In reality, his path has been long and difficult.

While acknowledging "every country has rights to protect their borders", he says Australia "can do better than this".

Shiao Lu Ooi's decision to come to Australia as an international student was based on a gut feeling.

The Malaysian-born 22-year-old initially considered pursuing a study in the United Kingdom, but was drawn to "something really inherent about Australia".

However, things didn't go as planned. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted Australia to close its borders in 2020, so Ooi had to complete her first semester abroad.

Ooi moved to Melbourne ahead of her second semester in 2022, after borders had re-opened. She recalls feeling insecure and anxious in the lead-up.

"I caught COVID on my third day here, and I knew nothing whatsoever about Melbourne at that point," she says.

"I remember being so scared and homesick, being like, 'I just want to go home. This is so tough, and I don't know how I'm going to navigate my life here'.''

Ooi says her experience was compounded by "rumours and misinformation" associated with COVID-19 and aggression towards Asian people during that time.

I was very, very scared, to the point I kept on asking people, 'could I go out?'Shiao Lu Ooi

In time, Ooi was able to explore her new city and form connections. She is now a youth adviser at the Centre for Multicultural Youth and the founder of Wombat Collective, a non-profit organisation that supports international students in engaging with grassroots initiatives.

She says connecting with international students and other people from diverse backgrounds in Melbourne has offered her "the community that I always wanted".

But Ooi believes COVID-19 has had a "spillover effect".

"I would 100 per cent say that COVID definitely has altered perceptions of international students very negatively, and that contributes to how these issues like housing, financial difficulties and securing work still impact [them] to this day."

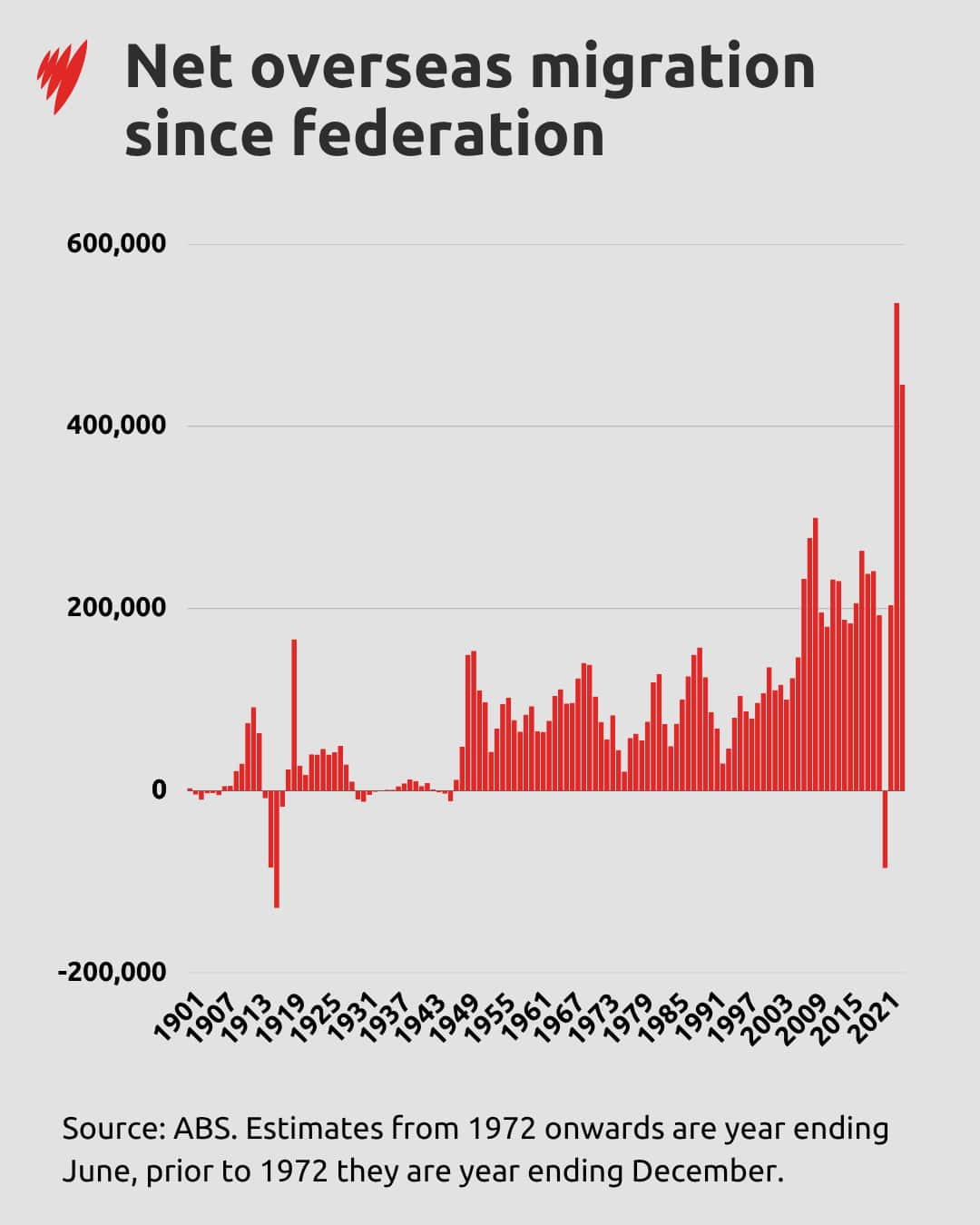

When Australia closed its borders in 2020, migration levels — sometimes referred to as net overseas migration (NOM) — entered a shortfall as international students returned home.

NOM refers to the difference between those who enter and leave Australia, and includes both migrants and Australians.

The re-opening of borders prompted a rebound in arrivals.

"We do expect a bounce back; that's just getting back to normal levels now," Stevens says.

"What we experienced with COVID was hopefully a once-in-a-life crisis, and we do have to expect a bit of economic and therefore political instability in the years that follow."

International students have also been singled out by some politicians for causing or exacerbating the housing crisis — a claim that has since been refuted in research from the Student Accommodation Council and the University of South Australia.

Stevens says this cohort is being "scapegoated for economic problems not of their making" as a means of political distraction, calling the recent discussion on housing a "complete furphy".

"At the same time, we're demonising a significant part of the Australian population who make important contributions to not just the economy but Australian culture and society overall."

Ooi agrees: "It is not one-dimensional; there are many national and global factors that contribute to the housing crisis."

"There are a lot of ways that I believe the crisis could be tackled – and this is not one of those ways, by pinning it entirely on international students," she says.

The scapegoating of migrants is not a new concept to many migrant Australians, including Carina Hoang.

The now 62-year-old academic and historian published a book in 2010 titled Boat People, chronicling the journeys taken by Vietnamese refugees, like herself.

She believes the meaning of the term has changed significantly.

"In my time, it's more describing this group of people who flee persecution, and their way of transportation was by boat," she says.

"I felt as if at that time [in the 1970s] that people were welcoming boat people with more compassion, with humanity, with some understanding."

I felt as if at that time [in the 1970s] that people were welcoming boat people with more compassion, with humanity, with some understanding.Carina Hoang

Later, Hoang says the term "became demonised".

"We didn't have a choice. Whether we went on foot, on the water [or] by air, those refugees are trying to flee hardship or persecution … and trying to find safety, even freedom, for themselves and their families," she says.

"Being judged by the term boat people because of the way they came, it's not right."

Hoang's journey led her to resettle as a refugee in the US in 1980. She migrated to Australia with her husband in 2006 and settled in Perth, where she has lived for the past quarter-century. She has since completed a PhD in refugee experiences and now works as the UNHCR's special representative to Australia.

"I have Vietnam as the country where I was born, America where I lived for 25 years, and then now Australia … Out of those three places, I would call Australia home.

I feel I belong here.Carina Hoang

This project was designed and developed by Jono Delbridge and Ken Macleod, with video led by Pranjali Sehgal, additional reporting from Amy Hall and Chris Tan, and research support from SBS Chinese and SBS Dinka. It was edited by Anna Freeland.

Your stories have shaped SBS for half a century. Together, we're just getting started. Join us as we celebrate 50 years of belonging on our SBS50 portal and SBS50 content hub.