This story contains references to suicide.

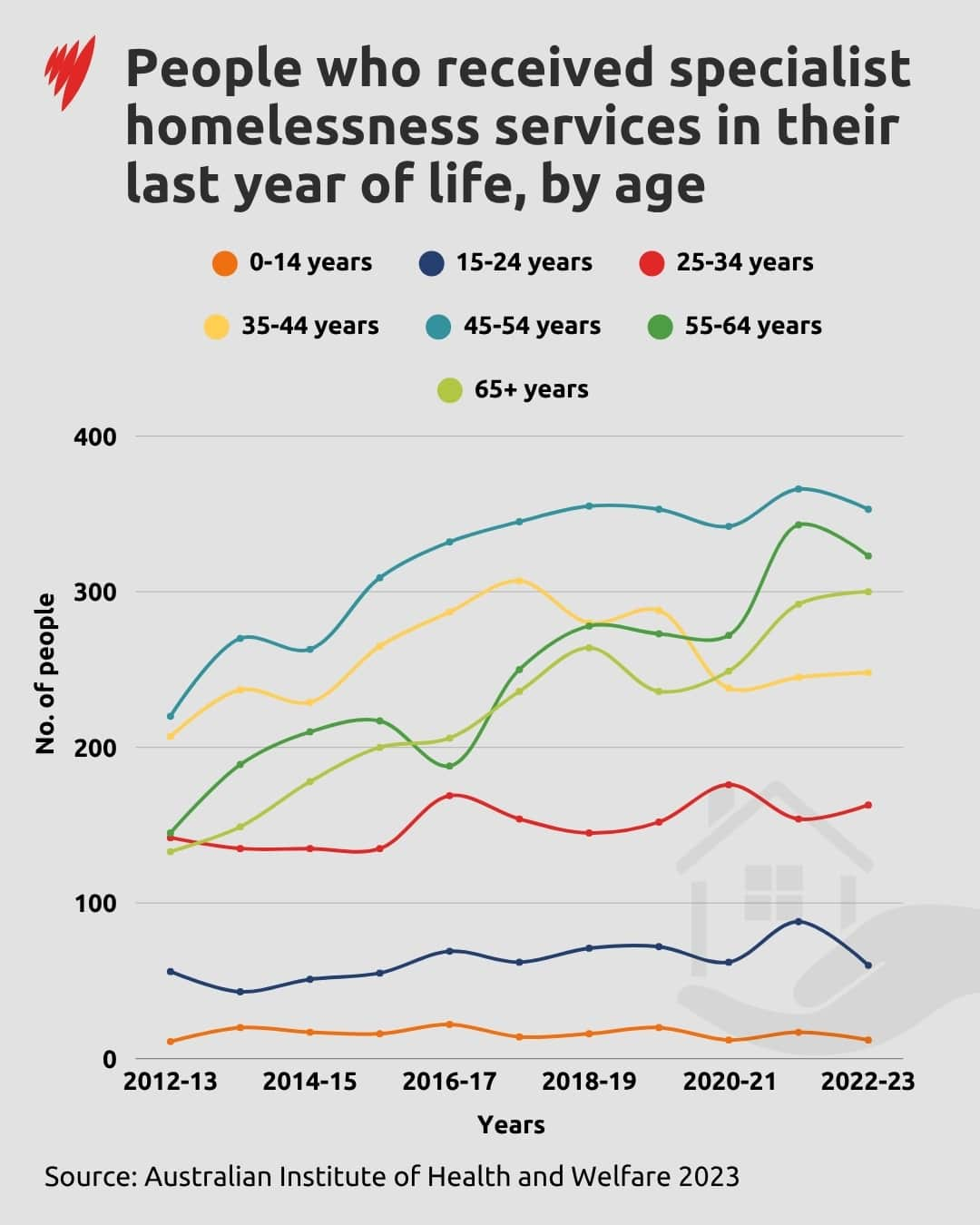

More Australians are dying while facing homelessness — and they're dying younger, often in their 30s to early 50s, according to new data.

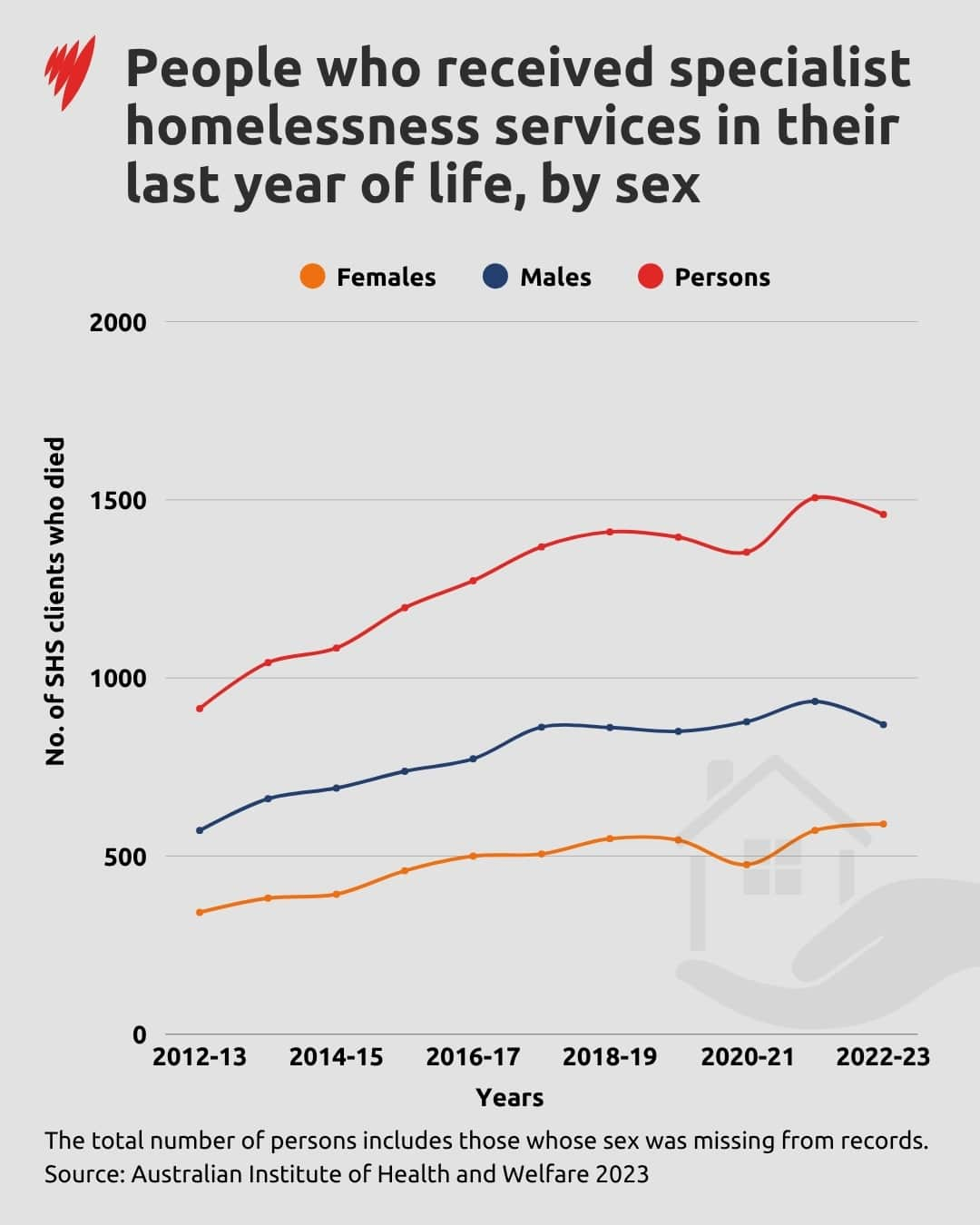

Some 14,000 people accessing specialist homelessness services (SHS) — agencies that provide services to respond to or prevent homelessness — died in the decade to 2023, according to an Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) analysis. The annual death toll rose from 914 to 1,459 over the same period — nearly a 60 per cent increase.

Almost half (45 per cent) of those deaths were in people aged 35-54, while about one in eight (1,700 in total) were people aged 25-34 and one in 77 (180 total) were children under 14.

The median age of death in Australia is 82, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. But the AIHW found, among those accessing homelessness services, the median age at death was 55 — 27 years younger.

The disparity was even greater for people sleeping rough. Their median age at death was 47, similar to those experiencing other forms of homelessness.

Kate Colvin, the chief executive officer of Homelessness Australia, told SBS News many of these deaths are avoidable.

She described the prevalence of death by suicide or overdosing as "devastatingly common" among those experiencing homelessness and for rough sleepers.

Colvin said a key factor exacerbating these avoidable deaths is a lack of affordable social housing.

While the federal government has committed to building 1.2 million homes by 2029 to achieve the National Housing Accord target, homeless people, and in particular youth, are struggling to access stable housing.

SHS supported around 280,000 people in 2023–24, with almost half of unaccompanied young people aged 15-24 seeking help still experiencing homelessness when their support ended. Unaccompanied refers to a person not living with a parent or guardian (if under 18) or living along (aged 18-24).

Social housing dwellings made up only 4.1 per cent of all households in 2024, a decrease from 4.8 per cent in 2011, according to AIHW data released this month.

Trauma compounded by homelessness

Colvin said that people seeking help from an SHS have often experienced some kind of trauma.

"A lot of people coming to homeless services are fleeing domestic and family violence. For children, it's abuse and neglect in the home and other forms of violence as well," she said.

"They then come to homeless services and often just cannot get access to the housing that they need to move on with their life."

A lack of stable housing has two effects, she said, "eroding hope" and "trapping" people in homelessness.

She said this creates further risks for people already experiencing mental health challenges and dangerous environments.

"It's very common for people, particularly if they're rough sleeping, to be subject to violence on the street. But also, when people are couch surfing or in rooming houses, they can experience violence," she said.

"That's where we see the suicides and overdoses as a direct consequence of those experiences."

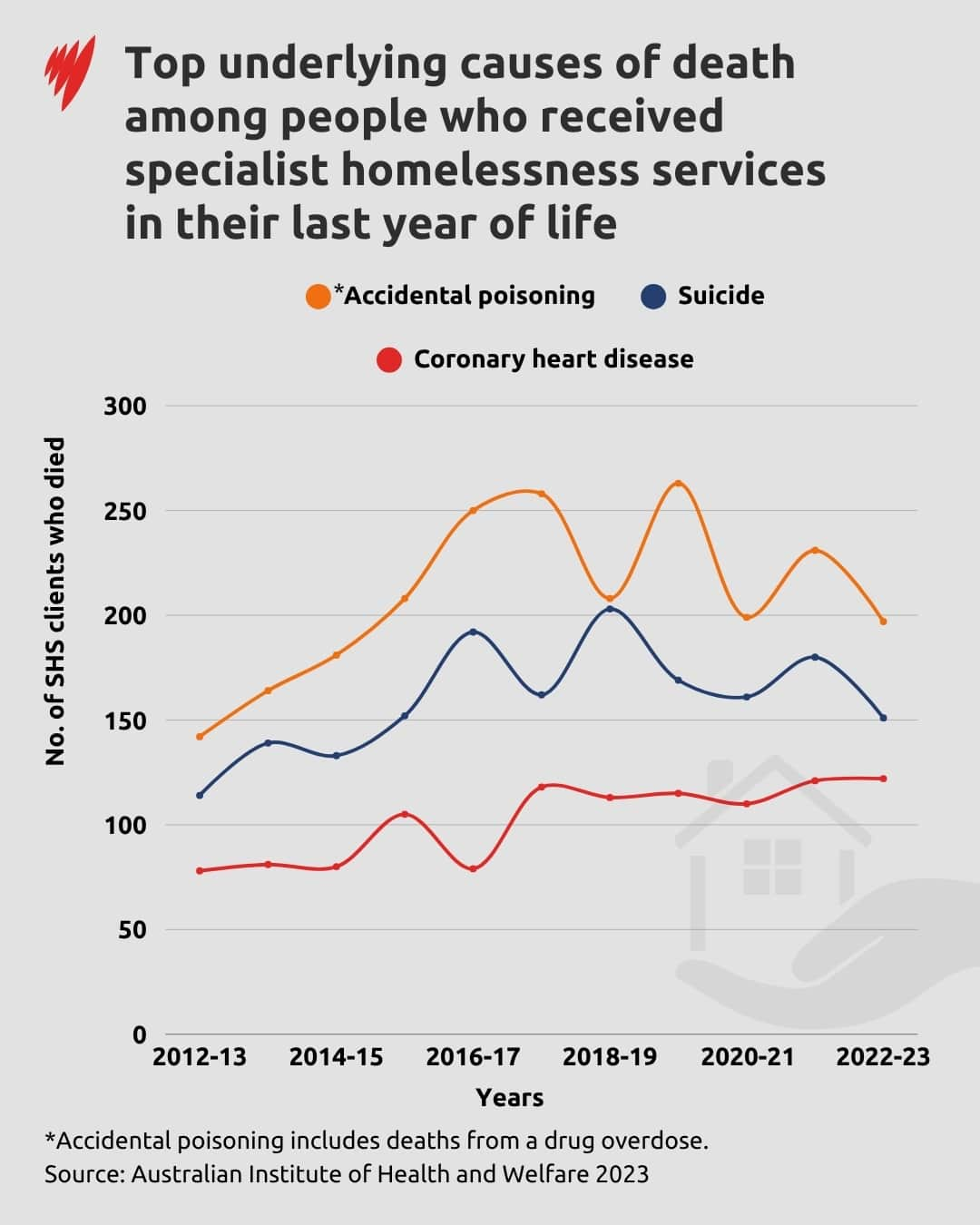

Accidental poisoning — which includes deaths from a drug overdose — was the top underlying cause of death among people who accessed SHS in their last year of life.

Accidental poisoning deaths relate to exposure to a substance in an amount that unintentionally causes harm. The most common accidental poisoning was caused by the consumption of the drug gamma-hydroxybutyrate or GHB.

Deaths by suicide, followed by coronary heart disease, were the other main causes of death for the study period of 2013 to 2023.

Liver diseases, cancers and other illnesses were also common causes of death.

Colvin explained that a lack of housing services also undermines a person's ability to seek medical help for a chronic condition or illness.

"These are often deaths and illnesses that are more likely to occur if they experience disadvantage across a number of areas of their life," she said.

"Particularly coronary heart disease, if you experience a lot of stress, you are not in a position to eat well and exercise. And then we know that heart conditions can be a consequence of all of those experiences."

Among males, the most common underlying cause of death was consistently accidental poisoning, 15 to 22 per cent, followed by suicide, 11 to 16 per cent and coronary heart disease, 7.4 to 10 per cent.

Among females, accidental poisoning caused 11 to 17 per cent of deaths, and suicide 8.8 to 16 per cent. These were consistently the two most common underlying causes of death, with rankings changing between years.

These top two causes were followed by a mix of other causes, including coronary heart disease, liver disease and lung cancer.

More men died in proximity to homelessness, data suggests

Around 8,700 males and around 5,300 females accessed SHS support in their last year of life over the study period, according to the AIHW.

Approximately two-thirds of SHS clients are female, with around 2 in 5 females experiencing homelessness at the start of support. While fewer SHS clients are males, around half are experiencing homelessness at the start of support.

Clinical psychologist Dr Helen Stallman who is also the director of the suicide prevention group Care Collaborate Connect, said that suicide prevention programs are often too focused on "being a saviour" after a suicide attempt, rather than addressing basic needs first.

"Everybody needs housing and everybody needs to be able to afford the basic things like food and things like that. And everybody needs to be around safe social environments," she said.

"Governments really haven't stepped up and solved that problem so that every Australian has housing."

She said that other stressors, like the cost of living, can also create mental health challenges.

"All those things make life more stressful as well. And if you're not functioning it kind of just has this flow on effect," she said.

Home ownership declining

Colvin said that homelessness services are struggling to keep up with demand.

"There's only a limited number of workers and they can only see so many people a day," she said.

"Homeless services are so under the pump, responding to people who have already come through the door, that they're very frequently having to close the door to actually just respond to people."

As homelessness continues to rise in Australia, the housing crisis has deepened, Colvin said, putting further pressure on services.

AIHW data shows that 1.3 million low-income households were experiencing housing stress in 2024–25, spending more than 30 per cent of their disposable income on housing.

Adults and families struggling with these costs could be on the brink of homelessness.

AIHW spokesperson Louise Gates said home ownership rates were falling, with fewer young people owning their own home, largely because of the increased cost of housing.

Home ownership rates declined from 50 per cent to 36 per cent among people aged 25 to 29 and from 64 per cent to 50 per cent for those aged 30 to 34, between 1971 and 2021, according to the AIHW.

The number of social housing dwellings increased by 45,200 between June 2006 and June 2024.

However, social housing dwellings made up only 4.1 per cent of all households in 2024, a decrease from 4.8 per cent in 2011.

What change is needed?

Colvin said there is an opportunity to address deaths among people experiencing homelessness.

"The upcoming NDIS negotiations between the states and territories around foundational supports for people with psychosocial disability are an opportunity to deliver life-saving change," she said.

"The most critical change needed is the creation of housing integrated with mental health care and support so people can escape homelessness and recover their health and wellbeing."

Stallman said that providing mental health support needs to be inclusive of those experiencing homelessness.

"If people aren't reaching out and keeping connected with people, they feel really alone and that reduces their ability to get that support when they do need help coping with the tough stuff," she said.

Support for people experiencing homelessness can be found at homelessnessaustralia.org.au

Readers seeking crisis support can ring Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at beyondblue.org.au and on 1300 22 4636.

Embrace Multicultural Mental Health supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Readers struggling with their use of alcohol and other substances can contact the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015 for free and confidential support 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.